In a companion report released earlier this year, we outlined why land use policies and practices—which have long been contentious and high stakes—are getting more scrutiny. We offered a rubric for conducting equity impact assessments of proposed projects and significant land use changes, such as rezoning, that often accompany them. This report extends that work, showing why and how land use tools should be upgraded (and integrated with other tools) to promote more inclusive and effective economic development—i.e., economic change that generates shared gains, including racial and social equity. Our goal is to encourage and inform a new generation of progress in local economies both large and small.

Across the country, there is broad-based interest in expanding good jobs, growing small and midsized businesses with local and diverse ownership, and making local economies and tax bases more resilient to shifts in trade policy, significant cuts in federal and state funding, and losses from extreme weather and other impacts of a changing climate. But the right steps for achieving the gains without displacing residents, making the cost of living even more unaffordable, or otherwise exacerbating inequality by race, class, or other traits are not always clear, especially for local decisionmakers in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

Likewise, with a call to make it easier and cheaper to build, Ezra Klein, Derek Thompson, and other champions of “abundance” have made long-standing proposals for regulatory streamlining—and more agile government and structured community debate—much more visible and politically salient. They offer vivid examples of how slow, litigious, and expensive the local development process can be in some places, especially when social equity, environmental sustainability, and other goals are emphasized via specific rules and standards. No question, the nature of the development process affects the quality of transportation, energy, and other infrastructure, the supply and cost of housing, and more. But development reflects core values too, as well as power and influence, and signals what a community thinks a worthwhile future should include.

Unfortunately, given that fact, land use policy and economic development are often considered separately, and the multiple ties between them superficially—or ideologically. As a growing body of ideas and practice underscores, many important economic development proposals are land-intensive and raise significant equity and effectiveness questions tied to land and its regulation, ownership, and value. As previous Brookings research has explored in depth, land also links the stakes of economic decisions at the neighborhood, district, or other “hyperlocal” scales to those at the city and regional level.

This report examines the stakes and offers a new framework for action (previewed in Figure 1). It is part of a larger project on the development and use of racial equity impact assessment tools for better decisionmaking. The project is a joint effort by the Brookings Institution’s Center for Community Uplift and the New School’s Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy.

A number of forces are converging to intensify the economic and fiscal pressure felt by local and state governments, with major implications for land development. Understanding these forces is critical if communities are to find viable ways to make inclusive economic development work as budgets are strained.

First, the housing affordability crisis—i.e., much wider recognition that it is in fact a crisis, along with rising prices themselves—has increased frustration about the mismatch between wages and the cost of living in the U.S., but also about gentrification, displacement pressure, and racial equity in land use planning and development. This, in turn, fuels skepticism about claims made to win support for real estate and other land development projects and job-creation proposals, which are often promoted as bolstering local government budgets.

Second, due to the Trump administration and Congress, this year has brought dramatic shifts in federal policy and spending that affect the full spectrum of subnational governments: state or territorial, local, and Tribal. For example, a massive and controversial party-line domestic policy bill, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025, made a wide range of cuts, from future Medicaid spending to clean energy production, while expanding or modifying certain tax incentives. In real estate, for example, the law made the Opportunity Zone (OZ) investment incentive—which purports to focus on “economically distressed communities”—permanent. The impacts of the OZ program, which was originally enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and has catalyzed over $100 billion of investment so far, have been mixed at best. Urban Institute analysis of accounting data and project case studies suggests that much of the invested capital has gone to build market-rate rental housing, with little focus on job creation in distressed neighborhoods and towns. More equitable outcomes are possible, for the OZ credits and other funding and financing tools, as we explore in this report.

In addition to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the annual congressional appropriations process (currently at impasse, producing a government shutdown) is likewise advancing a wide variety of cuts to federal spending that local communities have relied on, from criminal justice and rental assistance to emergency management and public education.

Third, for cities and counties especially, the risks and rewards in economic development proposals are taking on greater significance, along with a sense of urgency about jobs in light of inflation, recessionary fears, and uncertainties driven by steep and shifting tariffs.

For example, given intensified concerns about state and local finances, the stadium wars are back, along with conflicts over casinos and downtown redevelopment. In addition, communities, tech companies, utilities, and other players are drawing new battle lines over the proliferation of energy-hungry data centers. That’s thanks in part to hundreds of billions of dollars in private capital investment to support the diffusion of artificial intelligence throughout the economy. By some credible estimates, that massive investment will account for a larger share of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) this year than retail spending.

Economic and fiscal pressure is expanding on multiple fronts at once—some cyclical and some more structural, such as the aging of the population alongside a loss of immigrant workers (countering gains made during the post-pandemic recovery) and significant proposed cuts to federal research and development funding.

Strapped public budgets usually make commercial and industrial real estate developments especially attractive to local governments, in larger and smaller regions alike. Under the right conditions, such developments can be valuable sources of tax revenue.

To be sure, a robust conversation about fiscal innovation continues too, in public finance and budgeting. For example, the city of New York has traditionally used an accounting technique called the “surplus roll” to ensure a balanced budget, which for historical reasons is significantly larger than the city’s more recently created rainy-day fund. However, since FY 2022, the size of the surplus roll has fallen by more than half (from $6.1 billion to $2.3 billion), while the rainy-day fund has not grown—indicating that revenues are not keeping pace with expenses. New York state faces an even more immediate budget gap and future imbalance.

In principle, economic development strategies that can both grow revenue and reduce expenses or their growth—for example, from services that help alleviate poverty rather than prevent or shorten it—can be well worth investing in. And context is all important: In high-growth, high-cost, built-up cities such as New York, the pain of the housing crisis has drawn new attention to how land use is allocated and regulated, and the implications that has for inclusive growth. This makes high-cost cities a rich source of lessons for other communities, including revitalizing urban regions that aim to keep family incomes and the local cost of living in balance over time—an imperative highlighted in the 2025 Brookings Metro Monitor’s overview of trends nationwide over the past decade. Conversely, New York and other high-cost cities can learn from bold innovations elsewhere, as we show in this report, especially when it comes to deploying and integrating multiple economic development authorities and tools in new ways.

In the next section, we critically examine several strategic questions about local economic development—who and what it is for, how it takes shape—and then turn to what it would take to upgrade land use tools and integrate them with other essential levers for change in pursuit of economic development that is more inclusive as well as more effective and sustainable.

Everything old is urgent again: Local Economic Development 101

Three evergreen questions—or never-ending debates—help explain why, and along what paths, local economic development policy and practice remain so contested and continue to evolve. Upgrading and integrating land use tools to chart an inclusive economic future in communities nationwide depends on a clear-eyed understanding of these questions and their stakes.

First, is the aim economic growth or merely development? Some players and approaches focus on promoting local economic growth—i.e. growing the economic pie of a region (GDP), with a primary focus on where growth comes from: exporting goods or services to other regions, via what are known as “tradable” jobs and sectors, to create value and jobs locally. Other approaches focus mainly on developing real estate, which may or may not contribute growth but certainly signals vitality—a flow of investment capital or the construction or rehabilitation of a real estate asset, ideally deepening or broadening the property tax base.

A classic retail example illustrates the distinction between actual growth and narrower development: Opening a new hardware store on Main Street is not a driver of growth, at least not directly, because hardware stores, like many Main Street businesses, mostly sell to local consumers. Unless the regional economic pie is growing (for other reasons), opening a new store typically just shifts some business activity from wherever else local consumers were getting their hardware, and sometimes contributes to further development on Main Street.

Clearly, shifting local demand from Store A to Store B is not growth for the local economy as a whole. But opening a new industrial plant to make computer chips, batteries for electric vehicles, or medical devices is very different: Most buyers will be outside the region, so those manufactured goods are exports meant to bring income into the region and expand the economic pie. Rezoning and developing land to create those factories would be directly tied to making that export-driven growth possible (and so would infrastructure upgrades and other inputs for new manufacturing).

A new or redeveloped sports stadium, casino, or other “destination” is another kind of intervention altogether—one that underscores the importance of decisions about land use. A stadium may well draw visitors into a region and expand tourism (a form of export revenue), but that does not mean that the taxpayer subsidies that often go into making stadium deals, or the public health impacts of gambling, will pay for themselves. Frequently, according to a large body of research, such deals yield a net loss for the taxpayer over the long run, with gains accruing mainly to the workers and businesses tied directly to the venue and spillover business it may bring, such as local hotels and restaurants. Then there are the effects on real estate around the venue, including any higher prices and potential displacement (or enrichment or impoverishment) of area residents. It’s no coincidence that enforceable community benefits agreements were invented a generation ago to make major stadium development deals more equitable and their effects more transparent. Mega-projects such as new stadiums, casinos, and large data centers often have mixed effects, which makes discussing their merits that much more important—and complicated.

Economic growth plans and land development plans can complement each other, but they do not guarantee good jobs, small business growth, or other benefits for incumbent residents as opposed to newcomers. Local voters and taxpayers—in communities of color and poor and working-class communities, but often more affluent residents too—are understandably wary of promises that potentially disruptive and expensive real estate development is worth it, especially if taxpayer dollars or land concessions are attached.

Many a battle over stadiums and downtown revitalization plans has been waged on this terrain, and there are no signs that dynamic will go away any time soon. To the contrary, as outlined above, with local and state budgets strapped and borrowing capacity limited, the prospect of new tax revenues from land development without new households to serve—the typical case of commercial or industrial development—can be irresistible for public officials and vigorously touted by local news media and business. The pro-development case—and powerful coalition of interests it consistently animates—often warn that localities need to find ways to pay their bills, especially the costs of public services, which means pragmatically embracing commerce and industry on local land without too many special conditions attached. Six years ago, the competition between regions to host Amazon’s second headquarters starkly illustrated these pressures and conflicts, in New York City and many other communities.

Second, how should success be defined: Job quantity, job quality, or something else? Most local economic development proposals, however land-intensive they are, will not be widely considered successful, or widely supported over the long run, if they do not generate jobs. But what kinds of jobs, offering what wages and benefits, and to whom? And what else can reasonably be expected of “good” economic development?

Local economic development policy and practice have long been criticized for a narrow emphasis on creating jobs of whatever kind, whatever the cost to the taxpayer. This, after all, is a field long centered on the “attraction game,” with fierce, beggar-thy-neighbor competition among localities for employers and private investment. Local governments continue to market their locations to prospective investors and employers, especially large companies, offering an estimated $30 billion each year in tax breaks and other concessions to attract or retain firms—too often without knowing whether those are just windfall gains for businesses that would have made their decision about location even without the added incentives. Economic analysis suggests the incentives per se are rarely determinant, and tend to play a small role, at least in the competition between regions.

As Madeline Janis and one of the authors of this piece explained in an essay on the importance of creating good manufacturing jobs in the U.S., job quality—not just the number of jobs or questionable claims about how taxpayer subsidies change business behavior—has come into the mainstream in economic development, particularly over the last decade, after years on the margins.

Job quality, not just promises about the number of jobs a deal or project will create, is something policymakers can influence directly. This can be done at the transaction level—for example, by attaching conditions to taxpayer-subsidized projects and public contracts. However, it can also be done structurally—for example, by raising the minimum wage or legislatively mandating other job quality standards, such as paid leave and access to training. As shown in the nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute’s Minimum Wage Tracker, a diverse array of states have raised their wage floor—and begun to phase out the subminimum tipped wage for certain jobs—over the past five years, on a bipartisan basis. Many localities moved to raise their minimum wage a generation ago—for example, through local “living wage” ordinances. (Conversely, some states have passed laws that preempt their local governments from doing so.)

But as discussed in a recent Brookings report on inclusive regional growth efforts, decisionmakers and community stakeholders need to define what “good jobs” are in their context (i.e., in their local labor markets). That should not be limited to targeting a single dollar-figure benchmark regardless of worker skill levels and credentials, industry mix, or occupations in demand. The authors illustrate more flexible and powerful approaches that can inform strategies that move the proverbial needle—for example, by significantly broadening access to jobs that already pay well versus improving wages in other jobs and plotting mobility pathways between occupations as well.

Overall, support for good jobs has grown substantially, from the ballot box to legislatures and board rooms. Notwithstanding competitive pressures, anti-union political views, or other factors that continue to hold wages down for workers, a broad swath of the voting and taxpaying public, in addition to many types of employers, express strong support for good pay, measured against the local cost of living, as the essence of job quality. (In surveys, the public reports historically high levels of support for the role of unions and unionization too.) Over the past few years, in fact, a big-tent coalition of employers and worker advocates—the Good Jobs Champions Group—has made an evidence-based economic and business case, in addition to the moral case, for job quality in the U.S. economy. As part of that effort, employers, policymakers, worker advocates, and researchers have also highlighted key aspects of job quality that go beyond wages, such as feelings of dignity, recognition, and agency on the job along with relatively predictable work schedules and hours. The recent release of the largest-ever workforce survey of job quality, by Gallup and several partner organizations, underscores there is much room for improvement in the U.S. economy, but also how vital it is that we update the way we define and measure the economy’s successes and shortcomings.

In sum, the field of local economic development has long been called to account better for delivering higher-quality jobs and especially higher wages. But in recent years, champions of this core measure of more fair and equitable economic development success aligned around much more widely shared definitions and priorities. Crucially, that shift, taken up by governors and other elected officials, cuts across party lines.

For local leaders debating the highest and best use of land and other precious assets, it is important to recognize that this important shift is also linking job quality to productivity, economic growth, and the story behind persistent labor shortages—in ways not seriously debated in decades. For example, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Suzanne Berger, a leading expert on the evolution of U.S. manufacturing, recently highlighted the sector’s lagging productivity relative to other advanced economies. She emphasized the role of low wages as part of the “low-end trap” in which too many U.S. manufacturers find themselves: “We have low tech, low skills, low wages, low productivity,” said Berger, “and you can’t really fix any one of these pieces without trying to pull the ‘knot’ apart.” In that vein, recent Brookings research emphasizes the importance of cross-sector coalitions that tie economic mobility, and especially broader and more inclusive access to good jobs, to more effective and nimble strategies for developing critical industry sectors.

Other measures of success. Beyond job quality, however, with the rise of the environmental movement in recent decades—including the cause of environmental justice and case for climate action—economic development plans and proposals have also been expected to account for environmental sustainability with, for example, “green metrics.” Conversely, regardless of the tenor and support (or opposition) at the federal level at any given moment, “green growth,” in the global parlance, has become a significant economic development interest in the U.S., especially among state and local leaders keen for their regions to be competitive in cleaner, climate-smart technologies and services. Much of that interest is technology- or sector-specific—for example, manufacturing in Georgia’s “Battery Belt,” lithium mining and recycling in Nevada’s “Lithium Loop” tech cluster, geothermal extraction in California’s “Lithium Valley,” and the climate-adaptation-focused Resilience Tech Hub in South Florida.

The field has also been challenged to build wealth more inclusively, including through local business ownership (in part by developing more effective local business “ecosystems” and supplier pools) and shared resident or “community” ownership (as the city of Chicago has pursued with innovative public investment in recent years).

On the frontier of defining success in economic development, some are calling for broader indicators of well-being that go beyond economic measures. Not to be confused with “wellness” lifestyle choices that emphasize healthy habits and self-care, well-being embodies the powerful idea that jobs, income, and wealth are not ends in themselves, but help make possible “human flourishing.” Flourishing is something that economic development plans and deals have rarely emphasized explicitly and that they sometimes undermine in stark and measurable ways through, for example, large-scale land development that displaces residents and local businesses and, in the process, can weaken community bonds and social capital and compromise physical and mental health. This broader conception of what development is for—and of tradeoffs that come with particular approaches—echoes a global push in recent decades to promote and track human development and not simply define social progress in terms of a larger economic pie (GDP growth).

In sum, local economic development is contested and evolving in part because interest groups, a concerned public of voters and taxpayers, and workers and businesses alike are asking more of it. In the process, they are pushing for more robust, holistic, and far-sighted standards of success than narrow—not to mention questionable—promises of job creation.

Third, who decides and who benefits? Related to the push for higher and more holistic standards of success are the questions of who gets to shape economic development agendas and projects, and who benefits from them. The latter is most visible: Who gets the good jobs, business opportunities, and other gains? But it is shaped in part by the former question: Who governs and guides economic development? That is, who gets to decide, or meaningfully influence decisions, at critical stages of the process?

First is shaping “who benefits” (see sidebar below). The rise of hiring regulations related to when employers can ask about the criminal records of applicants, such as New York City’s 2015 Fair Chance Act, illustrate how the public sector has exerted influence on the private sector around hiring and job quality. More recently, the city has adopted a requirement that employers using AI tools to automate hiring decisions undergo a “bias audit.” Likewise, some localities use enforceable community benefits agreements (or similar contractual mechanisms), as referenced above in the context of stadium deals, to condition public subsidy on job quality standards, diverse hiring, and sourcing commitments by businesses and real estate projects.

The practical economic question of who benefits, which is also a moral and political one, has taken on added agency in the wake of the on-camera murder of George Floyd in 2020, the mass protests that followed that horrific event, and the call for much more bold and intentional effort to promote racial equity. But in the whiplash our nation has seen over and over (especially in an era of intense partisanship and social-media-fueled grievance politics), that call for racial equity, especially in economic opportunity, was followed almost immediately by an intense backlash attacking equity—along with environmental sustainability and other agendas—as dangerous and wrong-headed “woke capitalism.”

More specific to race, the backlash, now reflected in a wide range of federal and state policies and practices, has portrayed diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts as not only failed and unproductive but discriminatory, especially against white Americans. Key court decisions, centered on whether one’s racial identity alone constitutes “presumptive disadvantage” (for example, to win government contracts), have compounded shifts in business practices by some companies (to de-emphasize race-conscious programs) and much more widespread rhetorical attacks.

The attacks on racial equity are ongoing and intense, but many equity-driven efforts (with measurable results) continue, whether they explicitly target by race, gender, or other aspects of identity, or use place of residence or specific experiences to define and address disadvantage.

For example, efforts to expand contracting opportunities in both the public and private sector have huge stakes for the racial wealth gap; such efforts can have disproportionately beneficial effects on small business owners who are women, people of color, disabled, from low-wealth families, or otherwise disadvantaged. Such efforts can expand opportunity in a variety of ways—such as by removing barriers and promoting broadly valued “procurement excellence”—without the use of preferential set-asides. Procurement is a critical, if underutilized, lever for promoting more fair and equitable economic opportunity, including more broad-based business ownership and wealth, since state and local governments alone spend an estimated $2 trillion per year purchasing goods and services (based on census data) in addition to the “indirect purchasing” governments do by providing vouchers or cash benefits to households. Procurement policies and practices of the federal government, the world’s largest buyer of goods and services, matter to entrepreneurs and communities nationwide as well. And the trend toward concentrating federal purchasing with larger companies, documented in recent Brookings analysis, is deeply concerning. It reverses decades of inclusive progress, consistently supported on a bipartisan basis since the Second World War, that helped build small and midsized enterprises and fuel America’s global leadership in innovation.

Notwithstanding the backlash (and all the more important because of it), a number of leading organizations have organized tools for equity-driven analysis of a wide range of economic and social data in U.S. regions, plus intervention tools for improving outcomes. These tools have distinct strengths for planning and implementing racial-equity-focused or broader equity-focused efforts in economic development, since they disaggregate by race, geography, gender, and other variables in different ways and to varying degrees. For example:

Data tools: Brookings’ Metro Monitor is an annual report and data interactive; PolicyLink’s National Equity Atlas is a multifunctional resource created in partnership with the Equity Research Institute at the University of Southern California; the Upjohn Institute offers a Broadly Shared Growth Initiative Web Map; and the Urban Institute hosts an Upward Mobility Data Dashboard and has offered technical support to help regions use it effectively.

Intervention guides (“playbooks”): The International Economic Development Council, a practitioner trade group and learning community, has issued a Race, Equity and Economic Development Playbook; Brookings Metro has published a variety of research-based guides, including recent findings on five civic capabilities—based on years of engagement with regional leaders across the country—for overcoming barriers and driving inclusive growth; the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University has published a series of investment playbooks emphasizing the importance of high-impact projects and investability; Next Street has published actionable research insights based on the inclusive growth strategies the firm has helped shape in San Antonio, St. Louis, and other regions; and the New Growth Innovation Network has issued a number of topical playbooks, including on how to make technology-based economic development more inclusive and how to use impact investment to accelerate wealth creation for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.

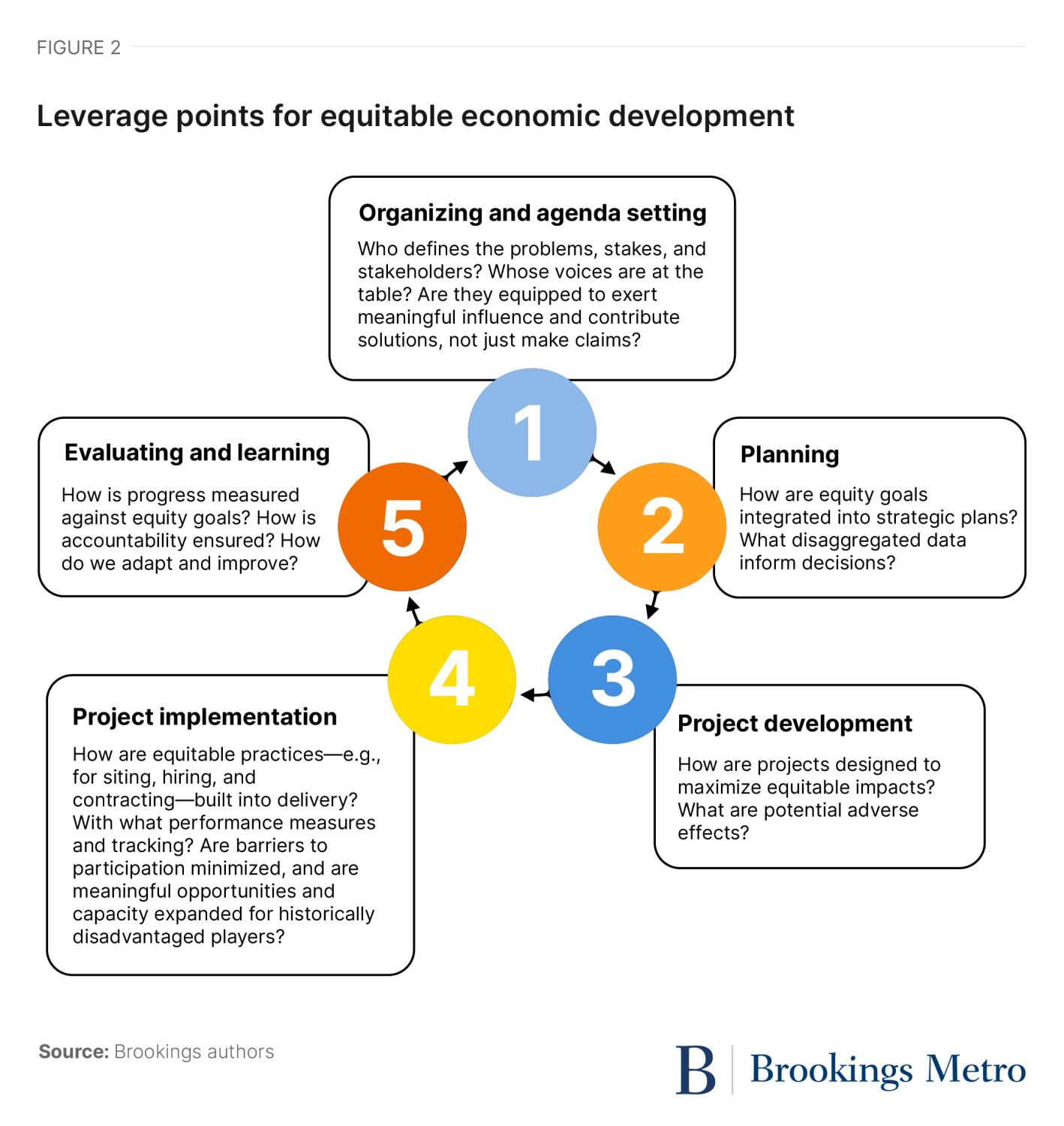

“Who decides” is the second part of this question. Who gets to benefit from economic development is shaped in part by who gets to influence and make significant decisions about it. Key decisions happen at more than one stage or level of granularity. For example, broad directional choices matter for a community or region in one set of ways and project-shaping choices in another, but both matter. We think of the leverage points for advancing more equitable economic development in terms of the stakes that present at distinct stages of defining, strategizing, and implementing local change agendas—which often engage state and federal players too—and then learning from them, to reinforce effort and make it more adaptive and accountable over time (see Figure 2).

The right tools for the job: Upgrading and integrating land use tools for economic development

The three evergreen questions above raise a fourth, which is the focus of this report’s contribution, and it is critical for equity as well as effectiveness: Does a locality, state, Tribe, or other jurisdiction have the right tools to achieve inclusive and fair economic development goals, and in that context, how should land use tools be upgraded and integrated with other tools? Here, we discuss the limits of land use tools in conventional use, offer an integrated framework that upgrades and integrates them with other tools, and illustrate with working examples from Austin, Texas; Pittsburgh; and New York City.

The limits: On its own, formal land use planning and regulation is a limited and blunt instrument for shaping things such as access to high-quality and affordable training, connections to employers offering good jobs, and more inclusive development of suppliers and other small and midsized businesses in a regional economy. More accurately, land use regulation such as zoning is not an instrument for ensuring those things, at least not directly.

This points to the need for upgrading land use tools and integrating them with other economic development tools. As for upgrading, some municipalities have moved to apply zoning reform as a way to address historic inequities created by zoning, or to pair zoning with other policy reforms related to tenant protection to promote development without displacement. Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Planning Commissioner Maurice Cox attempted to go even further, crafting the “We Will” comprehensive plan to guide not only land use, but capital program and other budget prioritization as well.

Next, integrating: While local governments have considerable sovereignty and discretion over land use, the institutions and processes for governing land use are often poorly connected—if they are connected at all—to tools such as workforce development, small business (or “entrepreneurship”) development, and other tools that are important for equitable economic development in a place, such as building the capacity of historically marginalized players and scaling up more inclusive investment models.

Further, the standard, transactional ways of promoting social equity within real estate development projects overlook the potential of integrating with the core value of a project: the ownership equity. As Brookings researchers and local innovators have shown, more imaginative and inclusive approaches have been demonstrated in real estate development, and pursuing these should be table stakes, or defaults, not extraordinary (see textbox below).

Drawing on best practice examples, a 2024 Brookings report outlined specific ways that private, public, community, and philanthropic actors can be more strategic and effective about pursuing equitable outcomes through real estate development. The research identified several critical shifts for policy and practice:

An action framework for more inclusive and equitable local economic development, including land use. The larger opportunity, and greater leverage, is integrating both goals and specific strategies that require mobilizing tools beyond land use regulation and innovative real estate development models (see Figure 1). We think of interlocking, mutually reinforcing strategies as aiming to affect four things that local governments and other governments can shape, even as technology and other macro forces shift specific opportunities and risks:

- Which “game” gets played, as defined by plans and their goals.

- Who gets to play in a meaningful, gain-sharing way.

- The rules of the game that structure participation and benefit.

- Which plays get investment to unlock value, access, and ownership.

The first element— “which game gets played”—highlights the value of holistic rather than siloed and piecemeal planning. Tools for more equitable economic development, including those that gauge the likely impacts of choices on racial and economic equity, are most meaningful when deployed within some normative and strategic framework that defines goals and success measures for a locality or region, as the impressive STL 2030 Jobs Plan does for Greater St. Louis, for example. Unlike many economic development documents we have analyzed over the years, that plan offers specific indicators of whether economic progress is inclusive or not to a broad-based, cross-sector coalition of actors, as well as news media and other observers. Employment indicators as well as indicators of business ownership and performance disaggregated by race, gender, and other traits are ripe for wider use across the country.

“Plans” can take many forms and offer guidance at more than one altitude, from transactions to places to broad domains of policy. In the framework, we are referring to areawide plans, as distinct from other valuable kinds of plans—say, for growing a priority industry sector or updating a range of labor standards to expand access and job quality for all workers.

Our research on the emergent use of racial equity impact assessment in local land use planning and development in New York City and other communities underscores the need for a specific plan for inclusive economic development. Without some framework of areawide goals, typically in the form of an adopted plan, it is challenging for project-by-project or zoning-decision-by-zoning-decision assessment to affect outcomes in a significant way.

One reason is that such assessments, while “pre-decisional” in the context of land use review, are downstream from the forces that generate certain kinds of project proposals and not others. Another reason is that among other functions, plans offer some normative understanding of what “good” looks like. In the implementation of New York City’s Racial Equity Report requirement, for example, land use proposals that include housing development must show alignment with the city’s overall housing plan. But no such adopted plan exists for the city’s economic development.

To be sure, a jurisdiction’s comprehensive land use plan and implementing zoning ordinance are, in and of themselves, long-range and systematic tools for shaping the decisions that real estate developers make about where and what to build, which are upstream of individual projects or deals. And localities are—at last—innovating ambitiously and pragmatically on the scope and use of comprehensive plans as well as stakeholder engagement and other practices for developing them. The city of Pittsburgh, for example, has launched Engage PGH, organizing comprehensive planning around a framework for “just transition” and emphasizing economic, social, and cultural resilience and shared gains. The city and its stakeholders evince a clear understanding that this means much more than updating land use regulation or permitting processes. It seeks to reimagine and align the kinds of strategies and component tools outlined in our framework, with broadly supported and understood success measures.

If plans define “the game” to be played with development tools and decisions, the other critical elements encompass the rules that structure it, who gets to play (the new and more established players), and what—exactly—becomes investable and gets investment. Here, over the past decade, the city of Austin, Texas illustrates considerable ingenuity, hard-won policy reforms that range from real estate development to labor standards, and a pathway to change that may, for some communities, represent an iterative, step-by-reinforcing-step alternative to Pittsburgh’s new, holistic planning approach.

In Austin, community and labor organizers, negotiating with the business community and local elected officials, have won a living-wage ordinance for city employees that for the first time includes subcontractors; a voter-approved bond for acquiring land and building affordable housing; zoning reforms to reduce the cost of development; dedicated funding for transit expansion; and other changes. While the city has much unfinished business (for example, charting a more inclusive future for the technology sector and its middle-skill and higher-wage jobs, and expanding public-private capital innovation to help), economic development practice in Austin is substantially more robust, equitable, and pro-worker than a decade ago, in part because the rules of the development game have changed. This is in the face of a very high cost of living and frequent opposition by Texas state government (for example, the state blocked, or “preempted,” Austin’s move to enact fair chance hiring and, for the first time in the South, paid sick leave for all workers).

Austin illustrates some of what’s possible when cross-sector coalitions work to change the goals of the game along with the rules, players, and financing, as well as other tools such as more equitable land use and economic development that unleash housing production and transit investment. These changes have, among other achievements, helped balance housing supply and demand and bring Austin rents down. This is housing production as a core component of inclusive economic development and anti-displacement strategy.

The examples of Austin, Pittsburgh, and other cities—including revitalizing urban regions such as Greater St. Louis and Akron, Ohio, which understand the urgency of reform and innovation—hold lessons for a wide range of other regions, including the nation’s so-called “superstar” metropolitan economies. New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, and other regions show some of the highest levels of inequality and most brutally unaffordable costs of living relative to the wages available to most of their residents, along with advanced technology concentration, diversified export industries, and other assets.

A number of these cities have shown they can pursue ambitious-yet-equitable development on a large scale, with more inclusionary decisionmaking as well as affordable housing production and other essential outcomes. In New York, the major rezoning and redevelopment around Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal is an exemplar (as documented by careful, independent analysis); time will tell whether a similarly large-scale rezoning-in-progress for housing and economic development in Jamaica, Queens likewise proves successful in terms of racial equity and other key goals.

For these high-cost cities in particular, our action framework makes several imperatives clear:

First, develop and adopt meaningful, broadly supported economic development plans that clarify what success means—i.e., the goals and guiding metrics. As an analog: New York City’s adopted housing plan reminds us of the many reasons why plans matter, from clarifying core values and organizing and mobilizing resources to designating priority metrics of progress and catalyzing projects that align with larger goals. The housing plan also provides benchmarks that enhance the utility of new decision tools to support equitable development, such as equity impact assessments of major project and land use policy decisions. It is a major gap that New York City (and other localities) have no such guiding plan for economic development—at least none to guide the highest and best use of precious land and public subsidy.

Second, create more consistent and transparent rules that attach equitable economic benefits to major development proposals. Clearly, equity reviews need to expect more than basic job projections, and regions that are serious about making the economy work for everyone should align interests around clear public benefits attached—for starters—to publicly funded projects and major public contracts. These rules are quintessential (and working models are well documented), but they lie outside the narrow remit of regulating land use.

Third, to support the effective application of rules and standards, develop a scorecard (or similar rubric) for weighing and making tradeoffs on specific projects or rezoning proposals. Public subsidy, like land, is limited and sought after, and both are important for making economic development more fair and inclusive. Their value is doubly important as fiscal pressure on state and local governments intensifies, amplifying the challenge of competing objectives. In a proposed mixed-use development, for example, any subsidy dollar invested in inclusive entrepreneurship (say, to reduce the racial wealth gap in business ownership and wealth) could instead go to buy down the cost of new housing (adding apartments or making them more affordable). Incentive- and point-based evaluation systems, such as the one used by Montgomery County, Md., suggest what rubrics can weigh and how they can function for public, private, and nonprofit developers as well as advocates and elected officials engaged in development debates. Other tools, such as the Urban Institute’s Capital for Communities Scorecard, also offer useful and adaptable reference points.

Fourth, modernize sector development strategies to embed inclusion goals, measures, and tangible mechanisms. Industry sectors with high shares of good jobs—and, by extension, strategies for growing them—are competitive and resilient over the long term, with smart land use as one foundation. But too often, inclusion goals and tangible mechanisms (such as local workforce linkages, local supplier development and supply chain building, and community or worker ownership models) have been under-resourced and subscale afterthoughts—or worse, portrayed as charitable extras rather than core strategies for driving success. That’s a problem, because a rising tide does not lift all boats, and sometimes, it is particularly hard to reach for the local “boats”—renowned technology innovation clusters such as the Silicon Valley, for example, have been much better at importing their talent than growing it locally.

A large body of evidence underscores that inclusion is not just a moral imperative, but also good for growth. The task now is to mobilize the smart efforts that achieve it. As highlighted in earlier Brookings research, a new generation of regional economic transformation efforts—from onshoring advanced semiconductor manufacturing to developing biotech, quantum computing, and other critical sectors—demonstrates what mechanisms show most promise, e.g., for promoting inclusive economic mobility over time and not just meeting a target wage floor, and relatedly, how productive cross-sector engagement can work to enable iterative learning and adaptation over time. Doing so is critical as the technology frontier and global markets, not just domestic policy choices, continue to shift.

Fifth, expand and equip local players to participate in co-creating equitable growth, especially at the neighborhood level. The key lesson of a generation of asset-based community development is that healthy neighborhoods are not created from the top down or from the outside in. Local governments, philanthropy, and commercial lenders and other business partners should prioritize supporting an ecosystem to develop the capacity of hyperlocal organizations to co-envision, co-invest, and co-lead planning and development projects.

Sixth and finally, mobilize public, private, and “blended” investment into programs and projects that prioritize inclusion, as defined holistically and in a context-sensitive way. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to what makes something equitable, and different communities face different challenges and have unique assets to leverage. At the same time, budget resources are finite and cannot address every need. By aligning available capital behind well-defined priorities (for example, through a new generation of scalable community investment funds), cities can make sure that plans do not sit on the shelf and become broken promises, while also offering a clear prospectus to the private sector and philanthropy—a path for multiple sources of capital to “crowd in” for impact.

Beyond false choices

In this report, we have critically re-examined several evergreen debates about what constitutes more equitable and valuable economic development, with a focus on how real estate development and land use tools in particular can be reshaped and productively integrated by local governments to advance racial and economic equity in tandem with other priorities. This means rejecting the false choice between economic inclusion and, for one, stronger and more resilient city budgets.

The opportunity to make the mutually reinforcing changes outlined in our action framework has been hard won. While a glance at the headlines might make it seem as though the same fights are happening again and again, especially over mega-projects, in fact there is real progress across the country, at long last, to integrate land use with plans and investment tools for economic development in the broad sense, from industry sector and “cluster” strategies to job creation and small business development to infrastructure and even climate resilience. That progress is yielding notable changes in the way that local governments, workers and small businesses, and real estate developers do business—but leaves considerable room for more innovation and institutionalizing change.

To be clear, integrating land use controls and other rules with equitable investment and more holistic planning is far from the norm. And changing that will require leadership that aspires to more than the regulatory streamlining and related reforms that champions of “abundance” have advocated. Those changes matter, but so does developing the right plans that define goals and a future worth having—since building faster and less litigiously is not an end in itself—and making it possible for a broader, more inclusive, and more diverse set of players and investments to happen.

The toolset we have discussed here, with robust land use review embedded in a broader framework, helps create the conditions for achieving inclusive economic success, environmental sustainability, and other goals. They offer the best hope of promoting the economic growth, development, and resilience many communities need, for fiscal and other reasons, while minimizing the risk of displacement and even greater inequality.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Generous support of the Robin Hood Foundation made this research possible. A number of examples were drawn from the innovative work and insightful feedback of local participants in the Regional Inclusive Growth Network, supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and research on inclusive real estate development supported by the Kresge Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees. For helpful comments on a draft, the authors thank Rick McGahey, Joseph Parilla, Maria Torres-Springer, and Sarah Treuhaft.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).