After over four years of fighting, the civil war in Syria is still clearly nowhere near its end. None of the three main power groups—Bashar Assad’s government forces, the Syrian opposition, or the Islamic State (or ISIS)—have been able to obtain a decisive victory.

Recent outside interventions haven’t dramatically altered the circumstances of any one group. Airstrikes by the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State—not supported by ground operations—have not resulted in strategic changes. And the unexpected launch of Russian military operations supporting government forces has only further confused the situation.

But that’s not to say that these outside interventions aren’t significant. To the contrary, the Russian military operation in Syria has clearly transformed the conflict into a geopolitical confrontation between Russia and the United States. At this stage, we can only hope that leaders of those two countries will not allow the confrontation to escalate into open armed conflict between them.

The Venn diagram

It would be a mistake to limit our analysis of the Syria situation to one about a possible confrontation between the two nuclear superpowers (though that’s certainly an important component), or to try to predict the dynamics of the conflict through that lens alone. And there is in fact a third important outside player in this conflict: Iran. To compensate for its much weaker military, Iran has spent significant financial resources to pursue its goals in Syria. Having signed a landmark nuclear deal with the West, Tehran will now seek to strengthen its position in its region.

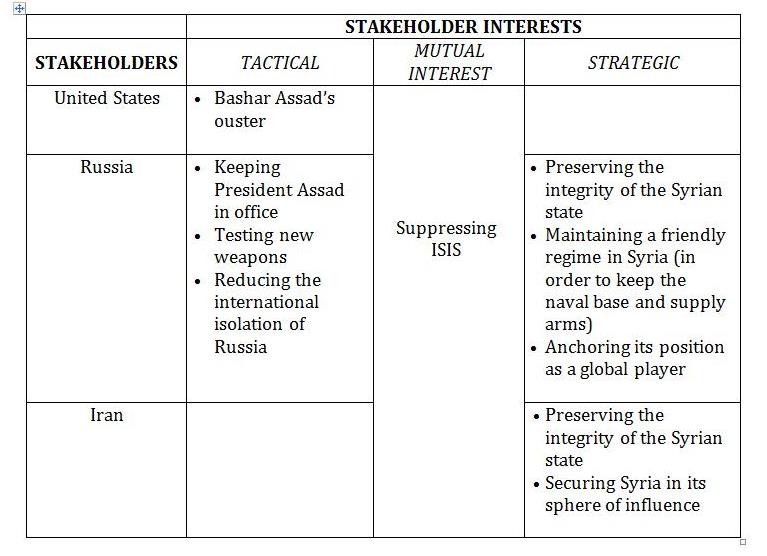

So beyond the warring factions themselves, we have a triangle of major external stakeholders in the Syrian conflict—and that dramatically expands the analytical space. It’s worth noting that there are other important players involved, namely Turkey and Saudi Arabia. However, those countries would be unlikely to play a significant role in the absence of U.S. support, which makes them price takers rather than price makers in the Syria conflict.

Let’s take a look at the interests of these three major stakeholders:

Comparing the interests of this triangle of stakeholders yields two important observations:

- First, among the three stakeholders, the United States has the fewest strategic interests in Syria. Washington’s main interest is suppressing ISIS. By and large, the United States does not care what happens to Syria after Assad—either Syria continues to exist as a single state, or it disintegrates into several components, with some areas outside of the central government’s control (analogous to Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya).

- Second, all three players have a common interest: to suppress, if not outright eliminate, ISIS. This suggests that a tripartite alliance could theoretically be established—though the actual possibility of that is extremely low. Alternatively, bilateral alliances could emerge, for which the third party would be the opponent.

Choosing sides

It may sound surprising, but the weakest partner in the triangle is the United States. By virtue of its dominant position in the world over the past 70 years, the United States has lost the habit of building political alliances based on equal partnerships and of taking into account the interests of other parties. This is especially difficult in alliances with countries whose principles, values, and interests are very different from America’s.

The U.S. position on the Syrian conflict makes it unlikely to come to an agreement with Russia. While leaders in Washington want Assad’s ouster, Russia views the displacement of a political leader by civil war or revolution as contrary to its understanding international order and thus unacceptable. This is a central basis for the general distrust between the two, in addition to Putin’s policies toward Ukraine.

[T]he Russian military operation in Syria has clearly transformed the conflict into a geopolitical confrontation between Russia and the United States.

At the same time, 40 years of broken diplomatic ties between the United States and Iran will take a long time to repair, and entrenched mutual distrust will make it unlikely that the two could have a meaningful dialogue over Syria. If Syria remains united, it’s possible that Iran would not object to U.S. efforts to replace Assad. His successor would likely be a general with an even better relationship with Iranian leaders, thus likely drawing Syria into a closer alliance with the Islamic Republic.

So, a Russia-Iran alliance—which has de facto emerged—seems likely to be the most stable and long-lasting. Although the two countries do not fully trust each other, they can find enough common ground to be partners rather than adversaries. Their strategic interests in Syria are not the same, but nor are they contradictory. Their combined military manpower (including resources from Iraq, which is now strongly influenced by Iran) and financial resources are sufficient to strengthen significantly Assad’s control over the country, even if they can’t completely destroy the Syrian opposition. While they might not be able to eliminate ISIS, they can reduce its influence in Syria and decrease the territory it holds.

A budding friendship

Although Russia has strategic interests in Syria, it has no intention to keep a military presence in the Middle East forever. President Vladimir Putin definitely envisions Russia as a global superpower playing a key role in peace negotiations in the region, but Moscow cannot deliver any significant economic support to Middle Eastern countries, nor does it have the soft power to win over permanent allies. In this respect, there is a limit to Russian strategic interests: Moscow must maintain good relations with the Syrian government in order to maintain its naval base in Tartus and remain the top arms supplier to Syria.

[T]he weakest partner in the triangle is the United States.

Neither of these goals conflict with Iranian interests. A Russian-Iranian alliance would encourage Iran to ramp up its own military purchases from Russia (and potentially those of Iraq). At the same time, Russia would have to accept Iran’s desire to secure Syria within the Iranian sphere of influence—an approach to regional affairs that Putin understands well. Moreover, the Shiite Iran-Iraq-Syria shield may protect Russia, to a great extent, from the Sunni support for Northern Caucasus Muslims rebels.

Such an alliance could definitely make Iran the dominant power in the region. On top of controlling vast hydrocarbon resources, the alliance would open new transportation routes, with Iran getting stable access to the Mediterranean Sea (through Iraq-Syria-Lebanon) and to the borders with Israel. All this would dramatically change the strategic situation in the Middle East.

The U.S. card

The United States can’t prevent this scenario by force without a major change in policy. Very few analysts believe the United States would undertake a massive military operation in Syria (in the range of 100,000 troops) or risk nuclear war with Russia over Syria. A Russia-Iran(-Iraq) alliance would enable the Syrian government’s army to expand its control over the country, dealing a serious blow to the Western coalition and its fight against ISIS.

For now, the White House is refraining from taking any serious action in Syria, preferring to let Russia taste the bitter fruits of its policy. It’s probable that Russia will soon (or at least eventually) face what the Soviet Union faced in Afghanistan: the widespread use of light anti-air missiles. In that case, the price of the Russian military operation in Syria would rise sharply.

But it would not change the strategic interests of either Russia or Iran in Syria. Similarly, the U.S. “wait and see” policy won’t help it formulate clear strategic interests and objectives in Syria. It’s not possible, after all, to formulate a strategy to achieve a goal you don’t even have.

Commentary

A three-sided disaster: The American, Russian, and Iranian strategic triangle in Syria

October 16, 2015