How do digital technologies affect governance in areas of limited statehood – places and circumstances characterized by the absence of state provisioning of public goods and the enforcement of binding rules with a monopoly of legitimate force? In the first post in this series I introduced the limited statehood concept and then described the tremendous growth in mobile telephony, GIS, and other technologies in the developing world. In the second post I offered examples of the use of ICT in initiatives intended to fill at least some of the governance vacuum created by limited statehood. With mobile phones, for example, farmers are informed of market conditions, have access to liquidity through M-Pesa and similar mobile money platforms.

How sustainable are these technology-based initiatives? Certainly in some cases they are intended as short-term solutions, such as is the case with post-disaster deployments of GIS platforms like Ushahidi. But in other instances the ICT initiative must be relied on until the emergence of consolidated statehood. Until states around the developing world have fully functioning agricultural extension services, for example, farmers must rely on programs such as the Grameen Foundation’s Community Knowledge Workers. It is too soon to say whether digital initiatives of this sort have the staying power to serve as long-term alternatives to a fully functioning state exercising proper and accountable administrative capacity. There are also important questions about the scalability of ICT initiatives. Different NGOs and community groups pursue similar initiatives in different areas, and sometimes even in the same community. This creates a patchwork of uncoordinated efforts. A final concern is found in what might be called governance displacement. To the extent ICT governance initiatives are successful in offering an alternative to a consolidated state, they may sap the motivation to improve state-sector governance capacity.

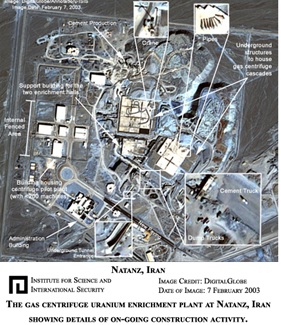

Gas Centrifuge Uranium Enrichment Plant at Natanz, Iran

ICT Can Strengthen State Governance Capacity

This brings to mind another type of ICT governance initiative. Rather than fill in for or even displace the state some ICT initiatives can strengthen governance capacity. Digital government – the use of digital technology by the state itself — is one important possibility. Other initiatives strengthen the state by exerting pressure.[i] Countries with weak governance sometimes take the form of extractive states or those, which cater to the needs of an elite, leaving the majority of the population in poverty and without basic public services. This is what Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson call extractive political and economic institutions. Inclusive states, on the other hand, are pluralistic, bound by the rule of law, respectful of property rights, and, in general, accountable. Accountability mechanisms such as a free press and competitive multiparty elections are instrumental to discourage extractive institutions. What ICT-based initiatives might lend a hand in strengthening accountability? We can point to three examples.

Example One: Using ICT to Protect Human Rights

Nonstate actors now use commercial, high-resolution remote sensing satellites to monitor weapons programs and human rights violations. Amnesty International’s Remote Sensing for Human Rights offers one example, and Satellite Sentinel offers another. Both use imagery from DigitalGlobe, an American remote sensing and geospatial content company. Other organizations have used commercially available remote sensing imagery to monitor weapons proliferation. The Institute for Science and International Security, a Washington-based NGO, revealed the Iranian nuclear weapons program in 2003 using commercial satellite imagery.[ii]

Example Two: Crowdsourcing Election Observation

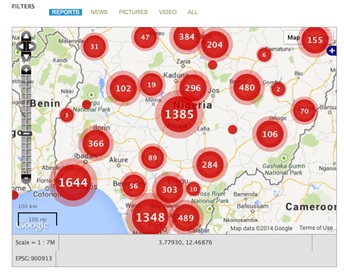

Others have used mobile phones and GIS to crowdsource election observation. For the 2011 elections in Nigeria, The Community Life Project, a civil society organization, created ReclaimNaija, an elections process monitoring system that relied on GIS and amateur observers with mobile phones to monitor the elections. Each of the red dots represents an aggregation of geo-located incidents reported to the ReclaimNaija platform. In a live map, clicking on a dot disaggregates the reports, eventually taking the reader to individual reports. Rigorous statistical analysis of ReclaimNaija results and the elections suggest it contributed to the effectiveness of the election process.

ReclaimNaija: Election Incident Reporting System Map

Example Three: Using Genetic Analysis to Identify War Crimes

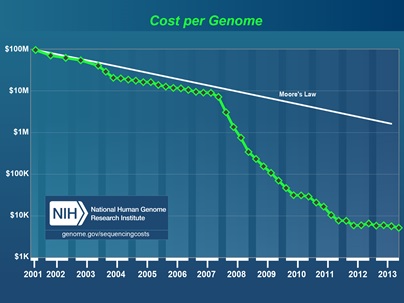

In recent years, more powerful computers have led to major breakthroughs in biomedical science. The reduction in cost of analyzing the human genome has actually outpaced Moore’s Law. This has opened up new possibilities for the use of genetic analysis in forensic anthropology. In Guatemala, the Balkans, Argentina, Peru and in several other places where mass executions and genocides took place, forensic anthropologists are using genetic analysis to find evidence that is used to hold the killers – often state actors – accountable.

Cost of Analyzing Human Genome Over Time

These are examples of the role digital technology plays in reducing barriers to holding states accountable. Rather than filling a governance void created by limited statehood, as we saw in the second installment in this series, digital technology is used to hold limited or extractive states to greater accountability.

Digitally enabled governance in areas of limited statehood presents compelling new possibilities for improving the lives of people around the world. While it is not without its limitations, plenty of potential exists, as the various examples we discussed suggests. So far, ICT as an alternative governance modality has showed promise. But much more work must be done before we can assess its true potential.

Part three of a three part series on ICT and governance. Parts one and two are available here.

Dr. Steven Livingston is professor of Media and International Affairs at The George Washington University. Among his more recent publications are Bits and Atoms: Information and Communication Technology in Areas of Limited Statehood (Gregor Walter-Drop co-editor) and Africa’s Information Revolution: Implications for Crime, Policing, and Citizen Security.

[i] Joseph Siegle, “ICT and Accountability in Areas of Limited Statehood,” in Bits and Atoms: Information and Communication Technology in Areas of Limited Statehood, Steven Livingston and Gregor Walter-Drop (eds.), (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[ii] Sean Aday and Steven Livingston, NGOs as Intelligence Agencies: The Empowerment of Transnational Advocacy Networks and the Media by Commercial Remote Sensing in the Cse of the Iranian Nuclear Program, Geoforum, Vol. 40 (4), 2009, pp. 514-522.

Commentary

The Transformative Impact of Data and Communication on Governance: Part 3

April 14, 2014