The Lessons from the Shutdown Series examines the costs and consequences of the recent shutdown and debt ceiling fights. In this piece, the authors examine the inability of Congress to deal with the Farm Bill and offer advice on how to move forward with the legislation.

With the fiscal crisis averted, lawmakers are turning their attention back to agriculture policy with the first conference committee meeting scheduled for this week. To avoid the mistakes of our past, we need thoughtful, process-driven reform; piecemeal tweaks to mandatory payment formulas just don’t work. The events of 1996 show us that trying to tweak entitlement qualifications with the intent of reducing total outlays is difficult, and can have unforeseen effects.

Agricultural subsidies are allocated through a variety of complex mandatory payment formulas based on unpredictable factors. Attempts to impose outcome-driven regulations (such as budget cuts) result in ineffective policy that either fails to achieve the goal, or accomplishes the exact opposite. We have seen this before. In fact, the last time Congress attempted to cap farm payments in 1996, aggregate spending for farm subsidies actually increased, peaking in 2001.

There are a number of similarities between the political climate that led to the 1996 farm bill cuts, and the situation unfolding today. Following the 1994 midterm elections, Republicans seized control of the House, and sought to slash the federal budget against the wishes of a Democratic president. They saw an opportunity to do so with the farm bill; Speaker Newt Gingrich aimed to reduce the price tag of the bill, restore market flexibility, and eventually “wean farmers off subsidies entirely.” After a year of debate – the longest in farm bill history – the bill finally passed in April of 1996.

Given the similarities between the 1996 farm bill debate and the ongoing one today, we can look to the outcome of the 1996 debate to gain understanding of how pressure for budget cuts may ultimately affect farm subsidies.

Notably, the Republican Congress amended several key provisions of the 1996 bill with the intention of reducing its budgetary footprint. Perhaps most important, support payments were no longer tied to current production levels, but instead were referred to as production flexibility contracts (PFCs).

According to this new provision, a farmer’s payment was based on contract acreage and the program yield for that commodity, meaning subsidies were paid irrespective of market prices. They became known as “decoupled payments,” because they decoupled payment from the market price of a crop; this allowed funding to be capped at a certain level and scheduled to decrease over time, regardless of market factors. By capping and gradually reducing farm subsidies, Republicans believed they had found a surefire way to reduce federal spending.

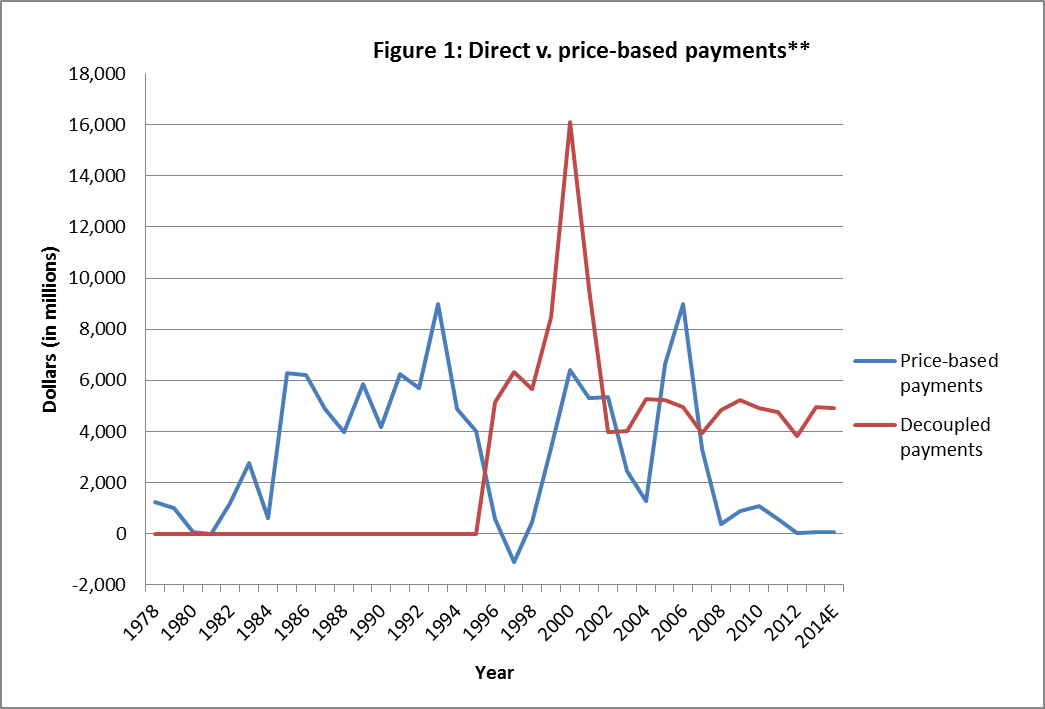

Despite the intended budget reductions in the letter of the law, mandatory spending proved difficult to regulate. Figure 1 shows the spike in decoupled (“direct”) payments after the 1996 Farm Bill passed, and the corresponding drop off in price-based payments. We see that direct payments, in fact, quickly surpassed price-based payments from previous years, increasing every year from 1995 to 2001, and saw a 500% increase over those six years. This is odd, given that direct payments were meant to cut funding to farm subsidies and to create more stability in outlays.

**Data on total farm payments come from the USDA Commodity Estimate Reports and Commodity Credit Corporation net outlay tables for FY14. USDA data are available here: http://www.fsa.usda.gov/FSA/webapp?area=about&subject=landing&topic=bap-bu-ce

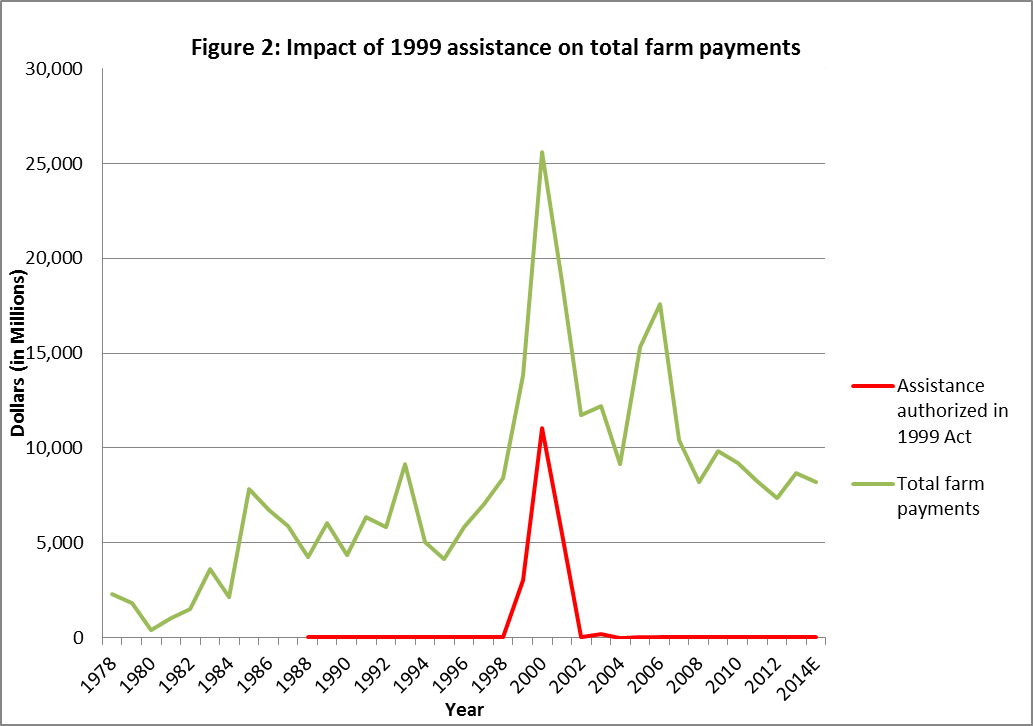

The reason for this counter-intuitive pattern in spending is that the new farm bill provisions were not able to account for fluctuations in the marketplace. After several consecutive years of low yield crops, Congress faced intense pressure to increase subsidies. In 1998, it effectively cancelled the cuts of 1996, and authorized a huge increase in subsidies in the 1999 Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act. This Act authorized subsidies called “market loss assistance” – an alternative form of direct payments – which increased outlays for 1999, 2000 and 2001, as shown in Figure 2. Consequently, total farm payments spiked upward between 1999 and 2001.

So what does this mean for the 2013 Farm Bill? Due to the complicated relationship between the letter of the law and actual federal outlays for mandatory spending programs (such as agricultural subsidies), meaningful change is unlikely to occur as a result of eleventh hour attempts at budget cuts. Farm policy certainly needs reform, but past experience shows that enacting cuts under the pressure of budget debate leads to ineffective policy that either fails to achieve its goal, or even produces the exact opposite effect. Reforming agricultural subsidies—or any mandatory program, for that matter—requires careful consideration and thoughtful economic forecasting, and a policy that can adapt to factors outside the immediate control of politicians. Last time we faced this situation, untested and outcome-driven (rather than process-driven) policy making had unintended consequences. Let’s not repeat the past.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Lessons from the Shutdown: The Farm Bill, Subsidies, & a Lack of Progress

October 28, 2013