This December, the latest scores will be released from the Programme for International Student Achievement (PISA), a widely followed international assessment. American press coverage—whether web-based, on television, or in old-fashioned print—will decry the mediocre showing of the U.S. and express astonishment at the performance of China. One problem. China does not take the PISA test. A dozen or so provinces in China take the PISA, along with two special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macao). But journalists and pundits will focus on the results from one province, Shanghai, and those test scores will be depicted, in much of the public discussion that follows, as the results for China. That is wrong.

Turn back the clock to when the last PISA scores (from the 2009 assessment) were released. About seventy nations participated. Shanghai scored number one in the world in all three subjects on which the PISA tests 15-year-olds – reading literacy, science literacy and math literacy – surpassing the previous top scoring nation, Finland. TIME’s headline declared “China Beats out Finland For Top Marks in Education.” The U.S. scored around the international average. Bloomberg’s headline was “U.S. Teens Lag as China Soars on International Test.” The New York Times almost got it right, warning readers in the second paragraph that Shanghai’s scores are “by no means representative of all of China.” But the remainder of the article treated Shanghai as if it were indeed representative of all of China. American journalists are not the only ones confused. In 2012, the BBC was still imputing China’s academic standing from Shanghai’s PISA scores, asking the provocative question, “China: The World’s Most Clever Country?”

How dissimilar is Shanghai to the rest of China? Shanghai’s population of 23-24 million people makes it about 1.7 percent of China’s estimated 1.35 billion people. Shanghai is a Province-level municipality and has historically attracted the nation’s elites. About 84 percent of Shanghai high school graduates go to college, compared to 24 percent nationally. Shanghai’s per capita GDP is more than twice that of China as a whole. And Shanghai’s parents invest heavily in their children’s education outside of school. According to deputy principal and director of the International Division at Peking University High School, Jiang Xuegin:

Shanghai parents will annually spend on average of 6,000 yuan on English and math tutors and 9,600 yuan on weekend activities, such as tennis and piano. During the high school years, annual tutoring costs shoot up to 30,000 yuan and the cost of activities doubles to 19,200 yuan.

The typical Chinese worker cannot afford such vast sums. Consider this: at the high school level, the total expenses for tutoring and weekend activities in Shanghai exceed what the average Chinese worker makes in a year (about 42,000 yuan or $6,861).

China has an unusual arrangement with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the organization responsible for PISA. Other provinces took the 2009 PISA test, but the Chinese government only allowed the release of Shanghai’s scores. The Financial Times quotes Andreas Schleicher, one of the OECD officials responsible for PISA, as saying, “We have actually done PISA in 12 of the provinces in China. Even in some of the very poor areas you get performance close to the OECD average.” Schleicher’s comment suggests that the secrecy guarding most Chinese provinces’ PISA scores isn’t hiding poor performance that may embarrass Chinese officials. Schleicher also said he was not surprised at Shanghai’s good showing, but he was surprised at how well rural provinces did on PISA.

Actually, the rural scores are difficult to interpret. PISA uses a two stage sampling design. First, a random sample of a nation’s schools are drawn, and then a random sample of students are drawn within the selected schools. The students are selected from a list of all students age 15 years and 3 months to 16 years and two months. This two-step randomization process ensures the production of a representative sample of students.

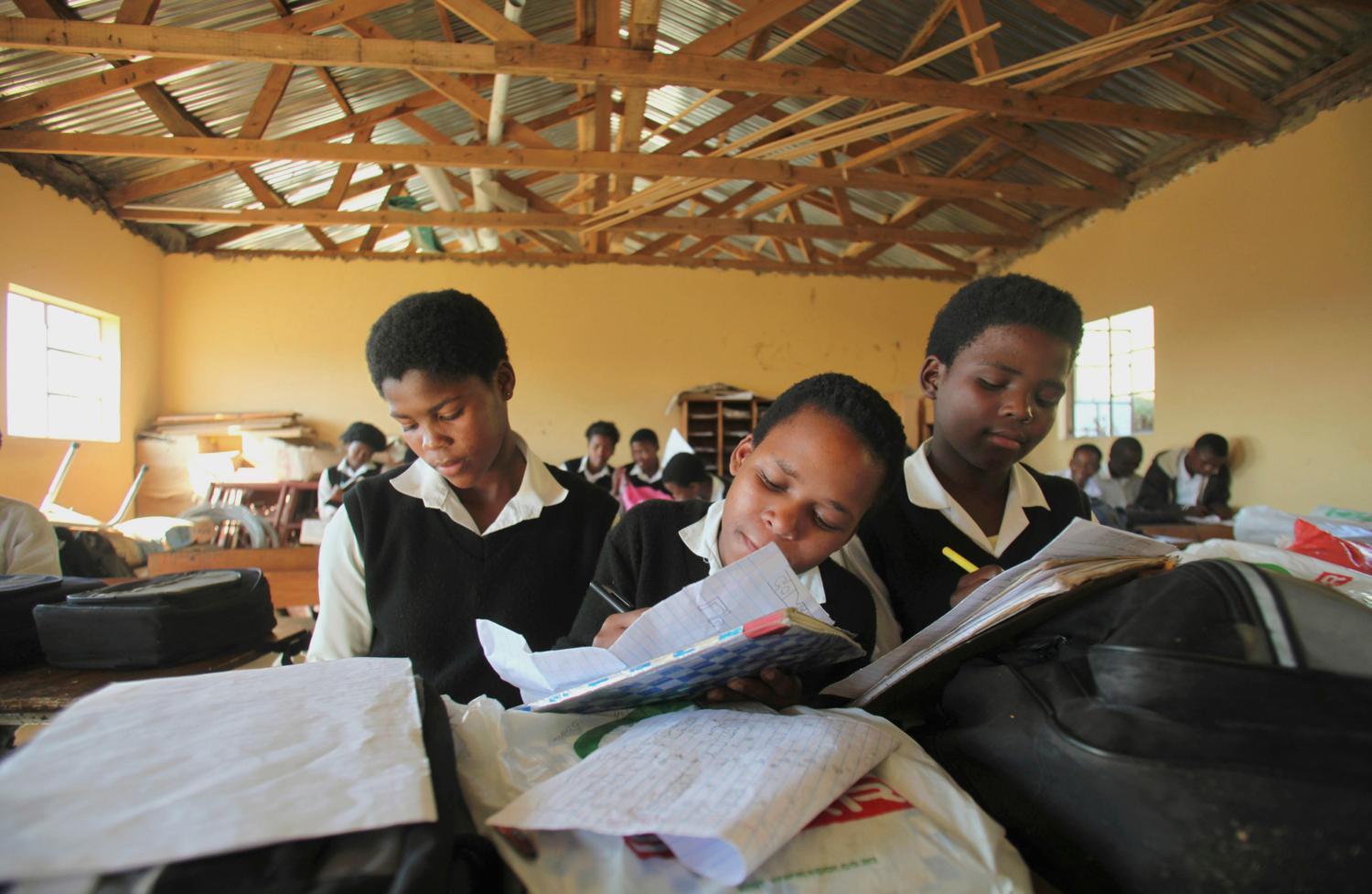

So to be in the PISA sample, a child must be attending school. The question raised by China’s rural PISA scores is: what population was the sample representative of? According to the Rural Education Action Program (REAP) at Stanford University, high school attendance rates are as low as 40 percent in poor, rural areas of China. The dropout rate runs as high as 25 percent in middle schools. The schools are often run down and poorly staffed. Classrooms packed with 130 students have been reported. Children must often work to help provide for their families, and secondary school fees (high schools charge tuition) are too high for many parents. It is clear that the student sample sitting for PISA is not representative of rural Chinese youth as a whole, but hails only from families strongly committed to formal education and able to afford the tuitions and fees of high school. It is also reasonable to assume that students not enrolled in high school, with an eighth grade education or less, would fare poorly on PISA. And, once again, do not forget that the provinces with PISA test scores were not selected randomly; they were those approved for participation by the Chinese government. All of these elements undermine the representativeness of the PISA scores.

About 66 percent of all children in China live in rural areas. The Chinese government’s policy initiatives in rural education are directed at school attendance, not higher test scores. A major reform effort targets migrant children. China’s remarkable economic boom over the past two decades has resulted in one of the largest mass migrations of people from rural to urban areas in human history. There are about 260 million migrants from the countryside now living in Chinese cities. Children in migrant families are severely disadvantaged educationally. Chinese cities, including Shanghai, require a hukou—proof of municipal residence, given at the place of family origin – to receive municipal services, including the right to attend public schools. The government’s official estimate is that 500,000 children in Shanghai are non-residents. The University of Southern California’s US-China Today recently estimated that Shanghai’s population comprises 11 million migrants and 13 million natives to the city.

Non-residents must either send children to private schools (often of low quality) or back to their rural villages. Every year, millions of children leave their families and return to the countryside, often to be cared for by grandparents or other relatives, because they cannot attend city schools. Recent efforts to reform the hukou system have been criticized as ineffective. In an article titled, “The Truth Behind the Boasts of Chinese Education,” Business Week investigated several troubling aspects of the Chinese educational system, including the discriminatory effects of hukou. In 2012, a fifteen year old Shanghai student, Zhan Haite, took to the internet to protest against the hukou system. She was being forced to return to Jiangxi province to attend high school, despite having attended primary and middle school in Shanghai. Jiangxi is where her parents were born. Zhan Haite was born in Guangdong, but the hukou is hereditary, designed to lock in a family’s socioeconomic status across generations.

What does all this mean for this December’s PISA scores? How should we react to what will surely be another stellar performance by Shanghai? First, everyone should place Shanghai’s scores in proper perspective. Shanghai has an economically and culturally elite population with systems in place to make sure that students who may perform poorly are not allowed into public schools. Second, the media should not present Shanghai’s scores as if they are indicative of China’s national performance in education. They aren’t, and no one will know how well China can perform on an international test until it participates, as a nation, under the same rules as all other nations. Third, the OECD should be far more transparent than it has been about the agreements it has with the Chinese government concerning who is tested and which scores are released. If China is treated differently than other PISA participants, the reasons for such special treatment need to be disclosed. And all data from the 2009 assessment of Chinese provinces should be released to the public domain so that scholars may conduct secondary analyses.

International tests are valuable for showing us how educational systems are performing all over the world. Nations can learn important lessons from each other, but the creation of such knowledge is dependent upon having all of the facts to properly interpret each participant’s scores. The OECD needs to do a better job of describing its assessment practices in China when the latest PISA scores are released in December. And the media needs to stop discussing the scores of Shanghai as if they are the scores of China.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).