This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

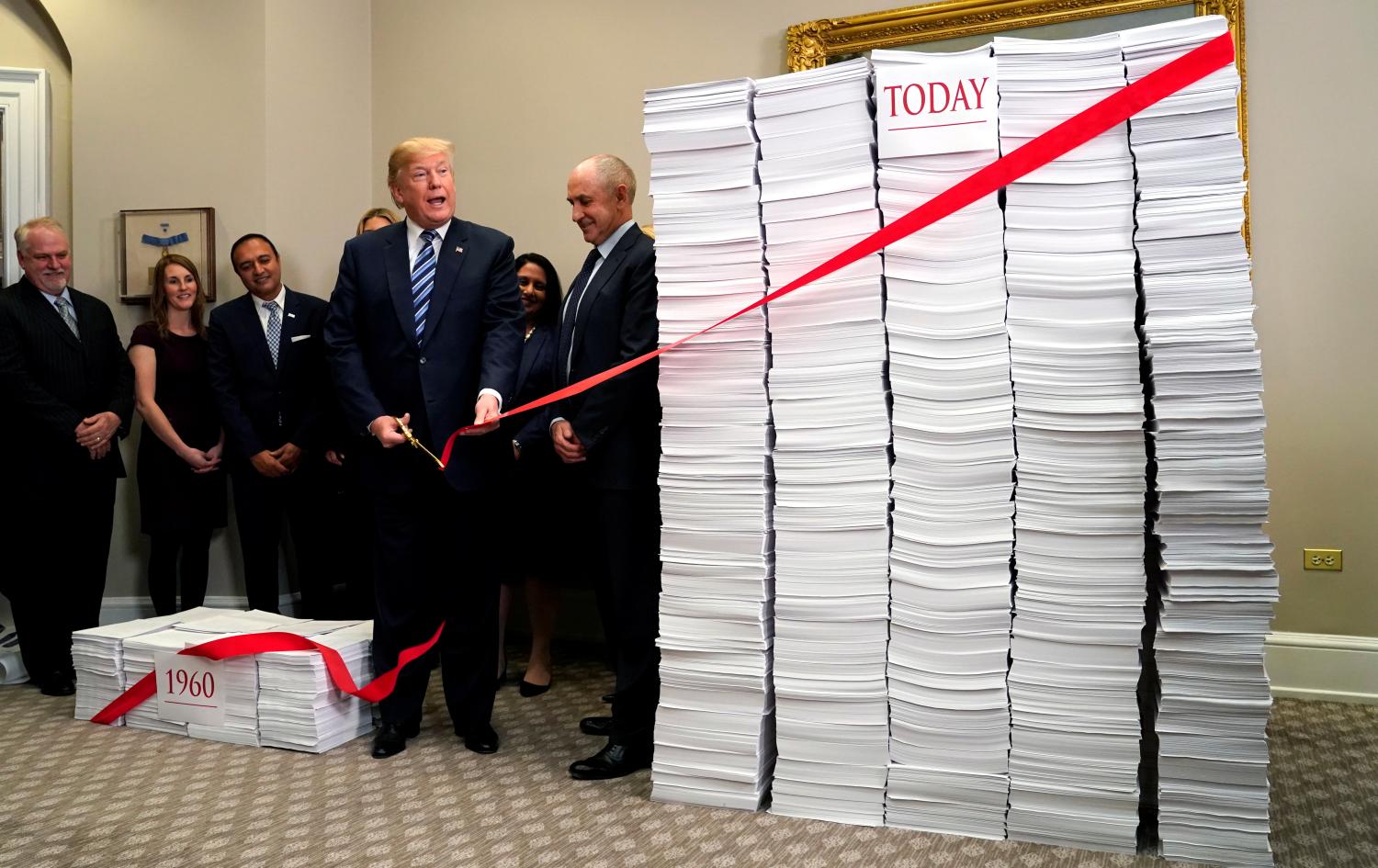

The Trump administration recently issued a report and supporting materials summarizing its regulatory cost cutting efforts. The report, authored by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), claimed total regulatory cost savings of $23 billion in Fiscal Year 2018. This is a notable increase from the $8.1 billion in savings claimed in the prior year. Moreover, the 2018 deregulatory items were on the whole more substantive than the 2017 list, which was bolstered by deregulatory actions already taken by Congress, initiatives largely formulated in the Obama administration, routine periodic update rules, and rules required by statute (a more complete accounting is available from a prior piece in this Brookings series).

OIRA has described its total claimed regulatory cost savings of $33 billion as “historic and meaningful regulatory reform.” Is this a fair claim or an overstatement? Answering that question requires context. Is a cost savings of $33 billion a big number? In the context of a $20 trillion annual economy, the answer appears to be “no.” ($33 billion amounts to one-tenth of one percent of the total U.S. economy). For present purposes, perhaps the fairer context is OIRA’s own estimates. OIRA claimed that in its first 21 months, the Obama administration imposed $245 billion in regulatory costs (the basis for this number is unclear but from OIRA’s report it appears to exclude benefits from Obama administration rules). Relative to Obama-era regulatory activity as measured by the Trump administration, reducing regulatory costs by $33 billion over 21 months appears relatively modest.

Where Did the Cost Savings Come From?

More than half of the $23 billion in 2018 cost savings came from one agency alone, the Department of Health and Human Services. Savings from most other agencies were very modest. Fewer than half of the 57 deregulatory rules cited by the Trump administration produced any measurable cost savings. At least 11 of these actions were temporary delays of Obama rules that may or may not ultimately produce long-term cost savings. Several other actions were merely declining to finish work on rules initiated under the Obama administration. The upshot was that the Health and Human Services results did much of the deregulatory work.

This begs the question of how Health and Human Services was able to generate more cost savings than other agencies. As Susan Dudley notes, some of these savings came from streamlining reporting requirements for health care providers. Such requirements are important because the health care industry is large and the government generally requires providers who participate in programs like Medicare to submit substantial documentation. If done well, streamlining such paperwork requirements may generate cost savings without reducing the quality of health care or oversight of federal health care spending. This would cut costs without reducing regulatory benefits, a goal shared by many prior presidents including the Obama administration’s regulatory review effort.

What About Benefits Lost from Deregulation?

A number of cost-cutting rules cited by the Trump report also reduced benefits to the broader public. Consider the Department’s delay of the Food Labeling Rule. Adopted late in the Obama administration, the rule required food labels to be revised to reflect improved understanding of how consumers actually read labels. For instance, the rule requires that food labels use portion sizes that better reflect what people actually eat, thereby allowing people to make more informed food decisions and improving public health. The rule also reflected improved understanding of how different foods impact health. One prominent example along these lines is requiring additional disclosure of the amount of sugar added to food. The Trump administration estimated the total benefits of the rule at $900 million.1

At the same time, the rule imposed costs (mostly in the form of devising and implementing the new food labels) of $1 billion. In short, the Administration estimated that the repealing the rule would provide society total benefits of $100 million ($1 billion minus $900 million). If these estimates are correct, then delaying the rule would indeed make society better off by $100 million. This would be a modest but real overall benefit to society. Yet OIRA’s tally shows a very different picture. By overlooking entirely the $900 million in benefits, the OIRA tally claims total savings of $1 billion. This does not reflect the action’s true impact on society.

This approach is also contrary to the longstanding and celebrated bipartisan executive order governing OIRA review of rules, which requires even-handed consideration of both benefits and costs. Perhaps more importantly, it neglects the foundational principles of cost-benefit analysis. Benefits foregone from repealing a rule (e.g., the $900 million in benefits from improved food labels) could just as easily be labeled as a “cost” to society imposed by deregulation. On the flip side, costs avoided by deregulating could be labelled a “benefit.” For cost-benefit analysis to be principled and sensible, both costs and benefits must be acknowledged and treated consistently. Detailed OIRA guidance on the White House deregulation executive order notes this issue and offers no general answers, instead encouraging agencies to use traditional accounting conventions.

Conclusions

The pace of cost cutting deregulation accelerated in 2018 as the Trump administration assumed firmer control of agencies and refined implementation of its deregulatory executive order. This list included more substantive measures than 2017 while still including a number of rules that did little in the way of cost-cutting. More importantly, however, the list included a number of rules that reduced regulatory benefits but did not incorporate those foregone benefits when tallying total cost savings. This marks an important departure from the long-standing approach to cost-benefit analysis and counsels in favor of carefully scrutinizing future cost saving claims.

The SEC disclaims responsibility for any private publication or statement of any SEC employee or Commissioner. The Article expresses the author’s views and does not necessarily reflect those of the Commission or other members of the staff.

The author did not receive any financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. He is currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

-

Footnotes

- All estimates assume the rule would be delayed for 20 years and total the impact in 2016 dollars.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).