The public sector plays a relatively small role in U.S. housing markets, compared to many other developed countries. Because housing is essential for families’ well-being, however, policymakers take keen interest in the availability, quality, cost, and location of housing. In a previous article, I presented a set of guidelines to make housing policy more efficient and equitable. This article explores the most important policies that currently shape U.S. housing markets, focusing particularly on how policies impact different families and housing market segments. I discuss the goals of three types of housing policies—taxes, subsidies, and regulations—and how each affects the efficiency and equity of housing markets.

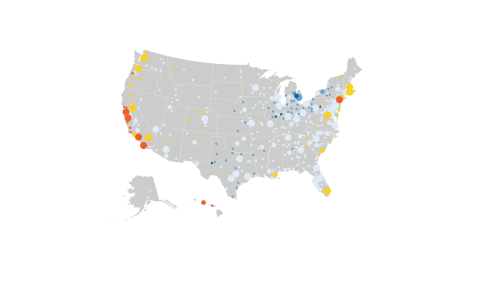

Federal, state, and local governments modify housing markets through a mixture of taxes, subsidies, and regulations, briefly summarized in Figure 1. All such policies have either direct or indirect redistributive effects. Taxes raise the price of the taxed good to consumers, often leading them to consume less. Taxes also generate revenue that governments use to pay for public services. On the other hand, subsidies have the inverse effect of taxes: They lower the cost of goods to consumers, leading them to consume more. Regulations can alter the price, quantity, or quality of goods in varying ways, so reading the regulation’s fine print is important to understand impacts.

Benefits from housing-related tax policies generally skew toward wealthier homeowners.

Local governments assess property taxes on all houses and apartment buildings in their jurisdiction. Property taxes are one of the largest sources of local governments’ resources and pay for schools, public safety, transportation, and similar public services. While homeowners directly pay property taxes, renters also implicitly pay these taxes as part of their rent. Many localities offer “homestead exemptions” that reduce the effective property tax rate for people who own the house they live in, relative to renters. Additionally, homeowners can deduct some amount of local property taxes from their federal income tax, which renters cannot.

Some local and state governments levy impact or linkage fees on new housing construction, essentially taxing new development. These fees can offset the costs of infrastructure needed to serve new housing, such as extending water and sewer lines or building additional schools. Unlike property taxes, which all property owners pay, impact fees fall primarily on developers and residents of newly built housing (both rental and owner-occupied).

Housing offers owners the opportunity to build wealth if the value of their homes increase over time. Federal income tax policy treats owner-occupied housing more generously than other financial assets, such as mutual funds or bonds. When homeowners sell their primary residences, they may exclude substantial amounts of capital gains from their income subject to federal taxes ($250,000 filing singly or $500,000 filing jointly). By contrast, households pay taxes on the full value of capital gains from other assets. The capital gains exclusion costs the federal government more than $30 billion per year in lost revenues.

Corporate income tax policy also matters for housing markets, especially for rental housing owned by investors. For example, the 1986 Tax Reform Act had several provisions that substantially reduced the tax benefits to owning apartments. New construction of multifamily housing declined sharply after the 1986 tax change, a shift attributed to the new law.

Housing subsidies for wealthy homeowners are much larger than for low-income renters.

By far the largest U.S. housing subsidy is the mortgage interest deduction (MID). As the name suggests, homeowners can deduct interest paid on their mortgage from their income subject to federal taxes. This subsidy cost around $60 billion in 2017, with most benefits going to wealthy families. The cost is projected to drop to around $40 billion in 2018, because the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the size of eligible mortgages and increased the standard deduction.

The largest housing subsidies to low-income families are housing choice vouchers and public housing, administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Collectively, these programs cost approximately $35 billion per year and support more than 4 million families. The primary program that encourages new development of below-market apartments is the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). LIHTC is an extremely complex program under which banks and other private companies purchase federal income tax credits, and the proceeds from the sale are used for affordable housing development. LIHTC costs the federal government around $8 billion per year.

Public spending on transportation infrastructure substantially impacts housing values. Decisions on where to locate highways, subways, and light rail lines can affect housing prices and rents for many decades.

Some housing regulations correct market failures; others impede market functions.

A wide network of regulations affect the quantity, quality, location, and price of housing in nearly all U.S. communities. Most housing regulations fall into three broad categories: land use regulations, consumer protection, and rent control.

Land use regulations

Zoning and related regulations specify how land may be used: where housing can be developed, how many homes can be built per acre of land, whether apartment buildings are permitted, and how tall buildings can be. Historically, the purpose of zoning is to limit negative spillovers of development on neighbors; for instance, tall buildings block sunlight for neighbors in shorter buildings. Land use regulations have become increasingly complex and onerous over the past 40 years, making it difficult for housing supply to meet demand and substantially increasing housing costs in some U.S. regions. Procedural requirements make the development process longer, more costly, and more uncertain, thus increasing housing prices further. In most communities, zoning makes it easier to build single-family homes—the largest and most expensive housing type—than apartments.

Local governments also oversee building codes that set minimum quality standards for homes and apartments. Modern building codes have substantially improved the health and safety of houses, relative to those built 100 years ago: For instance, they have reduced the use of hazardous materials and made homes more resilient to floods, earthquakes, and fires. But building codes also increase the price of housing, and not all provisions are clearly essential to health and safety.

Consumer protection regulations

The federal government regulates how households can borrow money to purchase homes. Mortgages are complex legal and financial contracts that most borrowers do not fully understand. Since the Great Recession, federal agencies such as the Federal Reserve System and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have written new rules so that banks cannot sell mortgages that borrowers cannot afford to repay. The rules also require lenders to provide borrowers with clear, accurate information on mortgage terms. While the new rules protect consumers and the overall health of the financial system, they might contribute to increased borrowing costs and make it harder for some families to purchase homes.

The federal Fair Housing Act protects potential renters and homebuyers from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, family status, or disability. Passed in 1968, this law aimed to eliminate blatantly discriminatory behavior. Prior to the law, landlords could refuse to rent apartments to black families, real estate agents steered black and white homebuyers to different neighborhoods, and mortgage lenders denied mortgages to black applicants based solely on race. Under the Obama administration, HUD adopted a new rule requiring local governments that receive federal funds to “affirmatively further fair housing,” in an effort to reduce continuing racial and economic segregation.

Rent control

Rent control is relatively rare in practice but almost universally disliked by economists. Local governments in some cities, notably New York City and San Francisco, limit the amount by which landlords can increase rent on certain privately-owned, unsubsidized apartments. Rent controls protect tenants when rents rise faster than incomes. Because it makes owning rental properties less profitable, rent control discourages landlords from maintaining apartments and encourages them to convert apartments to condominiums, thus reducing housing supply. California’s current housing crisis has resulted in calls to expand rent controls, despite evidence that this practice may drive up rents in uncontrolled buildings.

Public policies enacted by all levels of government affect the price, quantity, quality, and location of housing across the U.S. Some of these policies improve the efficiency and equity of housing markets, but other policies impede markets and make families worse off. In particular, taxes, subsidies, and zoning tend to benefit wealthy homeowners at the expense of lower-income renter families. The next article in this series will examine how current policies should change to improve housing outcomes, especially for middle- and lower-income families.

Ranjitha Shivaram provided excellent research assistance for this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).