Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

From June 2014 to January 2018, oil prices plummeted from $115 per barrel to $68 per barrel, a 41 percent decline. Prices reached a low of $28 on January 19, 2016.1 As a result, the oil-exporting countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) faced the longest period ever recorded of monthly consecutive losses in foreign-exchange reserves.2

For the 2015-2017 period, the GCC accumulated an estimated $353 billion in fiscal deficits, $76 billion in current account deficits, $270 billion in foreign-exchange reserve losses, and a reduction of $213.3 billion in sovereign financial net worth.3

As the recent shock in oil prices has been dominated by long-run structural transformations in the supply side of global oil and gas markets, the sustainability of the fixed exchange rate regimes in the GCC has been under question.4 In fact, over the last 43 months, foreign exchange markets in some GCC states were under considerable pressure. Spot markets were more volatile, and 12-months forward premiums spiked. During this period, Oman and Bahrain reportedly requested GCC financial support to defend their pegs, Saudi Arabia imposed additional regulatory controls on forward market operations, and Qatar had to tackle a major financial shock produced by regional geopolitical events.

This policy briefing examines the fundamentals of the GCC currency pegs and the capabilities of monetary authorities to sustain them over time. It argues that, although fixed exchange rate regimes are still optimal for all the GCC states, the ability of policymakers to support the pegs varies markedly across the region. The balance of payment pressures caused by lower oil prices and heightened geopolitical risks have generated “peso problems” and increased the chances of liquidity crisis and currency events, particularly in countries with less financial buffers and a lower ability to tighten fiscal policies over the short term.

As a currency event in one of the GCC states may have a contagion effect on others, and given the asymmetries in economic size, reserve adequacy, and macroeconomic imbalances in the region, further regional financial cooperation is necessary.

As a currency event in one of the GCC states may have a contagion effect on others, and given the asymmetries in economic size, reserve adequacy, and macroeconomic imbalances in the region, further regional financial cooperation is necessary. However, political and diplomatic disputes, amplified by the current blockade on Qatar imposed by Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), make regional cooperation difficult. In the last section, this briefing introduces policy alternatives for the creation of liquidity support arrangements under the current scenario of political divisions and presents possible roadmaps for future developments under different regional scenarios.

Origins of the Currency Pegs in the GCC

The current exchange rate regimes in the GCC are a product of the collapse of the Sterling Area in the late 1960s and the par-value system in the early 1970s. While most countries moved toward greater exchange rate flexibility following the disintegration of the Bretton Woods System in 1971-73, the GCC states opted to anchor their currencies to a stable international reference. After a period of Gulf-wide currency revaluations and adjustments during the oil boom and following the depreciation in the value of the U.S. dollar (USD) in the 1970s, Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE hard-pegged their national currencies to the USD at the current rates of 0.38, 3.64, and 3.67, respectively, between October 1978 and November 1980. Oman adjusted its hard peg to the USD to the current rate of 0.38 after devaluing the Omani rial in January 1986. Saudi Arabia hard-pegged to the USD at the current rate of 3.75 Saudi riyal just after a smooth devaluation between June 1981 and June 1986. Finally, by fixing the Kuwaiti dinar to an undisclosed currency basket in which the USD clearly had a dominant position, Kuwait was the only country in the region to rely on a “softer peg” to the USD.

In 2003, amid GCC discussions about the possibility of creating a common currency by 2010, all members decided to officially transform their de facto peg to the USD into a de jure peg. Kuwait, however, re-pegged to an undisclosed currency basket in 2007 in response to inflationary pressures caused by the depreciation of its real effective exchange rate. Ultimately, the monetary union did not move forward because Oman opposed the public debt limit set as a condition for integration, and the UAE objected to the dominant position Saudi Arabia wanted to play in the proposed regional central bank. Current political and diplomatic disputes within the GCC make the prospects of further pursuit of a monetary union unlikely in the future.

Economic fundamentals of the GCC currency pegs

Traditionally, exchange rate regimes are constrained by the monetary policy trilemma—a tradeoff between exchange rate stability, monetary independence, and capital market openness. In this sense, fixed exchange rate regimes are only sustainable if they are combined with capital controls or with a passive monetary policy. As globalization tends to make comprehensive capital controls ever more ineffective or undesirable, currency pegs are often associated with limited monetary independence. Under fixed exchange rate regimes with full capital mobility, central banks have to observe the interest parity condition (i.e. follow suit with changes in the interest rates of the issuer of the anchor currency). If business cycles within the “currency area” are not synchronized, the costs of maintaining interest rate parity can rise, producing pro-cyclicality and high volatility in inflation and growth.

GCC states faced this “mundellian trilemma” during the period of high growth in the 2000s and especially during the peak of the international financial crisis in 2007 and 2008, when their central banks were not able to control inflation and non-hydrocarbon GDP growth, despite the quantitative measures they took. It was in this context that Kuwait decided to move back to a slightly more flexible peg in 2007.

However, despite the aforementioned issues, petro-pegs have served the GCC states well. Inflation expectations have been anchored, real effective exchange rates have remained stable, and balance sheet risks and transaction costs have kept low. By providing nominal stability, the exchange rate regimes of GCC states have boosted the credibility of monetary authorities and favored long-term GDP growth. In fact, over the long run, the GCC outperformed advanced economies and emerging markets both in terms of GDP growth and monetary stability.

A closer look at the fundamentals of GCC economies would support the idea of fixed exchange rate regimes based on conventional pegs to the USD as the optimal macroeconomic policy framework. The reasons are grounded in eight main points:

- As small, open, oil-dominant economies in which per capita hydrocarbon production is high, GCC states tend to have large and structural fiscal and current account surpluses, allowing them to accumulate sizable war chests and hold positive net international investment positions. Such high levels of savings can be used to withstand temporary deficits and avoid large recessionary adjustments.

- Real effective exchange rates are relatively stable because the elastic supply of low-wage expatriate workers from Asia in GCC labor markets restrains pressures for higher wages in the private non-tradable sector (especially construction and services). This prevents cost-push inflation and Dutch disease problems during demand surges, curtailing real exchange rate appreciations during oil booms.

- Domestic households and firms remain insensitive to changes in real and nominal interest rates in the GCC due to underdeveloped financial and capital markets. This makes monetary policies relatively ineffective in the region and the cost of not having independent monetary policies low.

- The stocks of foreign portfolio investments are low, and government and government-related entities have a dominant position in total deposits, which creates limits for large and persistent gross capital outflows or dollarization in the GCC.

- GCC governments exert indirect control over the assets of entities that are technically sovereign by extension. Those include the non-state assets of firms and individuals whose main activities are national and rely on kinship of the royal families and their prime allies and connections. This makes the liabilities of the public sector de facto limited by assets that are private but “sovereign by extension.”

- Fiscal policies are efficient in rebalancing the economy while the political risks of multi-year fiscal retrenchment plans are manageable because reductions in public expenditures are concentrated in sectors dominated by expatriate workers with high mobility and residency permits linked to employment contracts.

- Alternative exchange rate anchors such as the IMF Special Drawing Rights, other baskets of major currencies, the Euro, gold and oil do not provide substantial benefits in terms of overall import or export stability for the GCC. Oil prices are set in USD. Additionally, while the composition of external trade in the GCC has changed significantly, with trade now being dominated by Asian partners, many of those Asian countries also anchor their currencies by hard or soft pegs to the USD. In fact, the role of the USD as an anchor currency for the world economy is much higher today than it was when the GCC states introduced their hard pegs in the late 1970s and early to mid-1980s.

- Any movement toward more flexible exchange rate regimes would pose significant credibility risks to the monetary authorities and heavy demands in terms of institutional reforms in foreign exchange markets and central bank operations.

If the current foreign exchange rate regimes are still the optimum choice, the remaining question is whether currency devaluations would support a rebalancing of GCC economies considering persistent low oil prices.

There is a general lack of material benefits from devaluations across the GCC. Both exports and imports are inelastic to changes in relative prices, and eventual positive quantity effects in terms of these variables do not offset cost effects in economies where imports dominate the markets for goods and labor. In fact, according to key econometric studies, the responses of the current account balances to changes in the real effective exchange rates in the GCC are either not statistically significant or move in the opposite direction of most other traditional cases, which implies that a devaluation is either insignificant for the external position or can even reinforce current account imbalances.5

This is a counterintuitive outcome associated with situations in which the Marshall-Lerner condition does not hold; devaluations or depreciations do not generate improvements in the trade balance because of their negative cost effects on imports, including capital goods, intermediary products, and labor. This stands even for GCC economies with a more diversified export base, such as the UAE and Bahrain, where non-oil exports are mostly re-exports or services provided by sectors with a very high rate of expatriate employment. For instance, a 10 percent real devaluation is expected to generate a deterioration of non-oil trade balance of 4 percent for Kuwait, 3.1 percent for Qatar, 2.8 percent for Saudi Arabia, 2.1 percent for Bahrain, 1.7 percent for the UAE, and 2.3 percent for Oman.6

GCC devaluations would not only hinder non-oil exports and diversification but would potentially create conditions for capital flight, banking crisis, and other balance sheet problems associated with currency mismatches.

GCC devaluations would not only hinder non-oil exports and diversification but would potentially create conditions for capital flight, banking crisis, and other balance sheet problems associated with currency mismatches. Other international experiences have shown that ineffective devaluations often generate pressures for further devaluations, creating market disorder and financial instability.

Ineffective expenditure switching tools and the lack of monetary policy independence suggest a very difficult environment for macroeconomic policymaking in the GCC, especially because fiscal policies are generally considered a bad instrument to address current account deficits. However, fiscal policies tend to actually be more effective in hyper-undiversified oil economies. For instance, while a 1 percent decrease in government spending for a broad sample of oil exporting countries improves their current account position by 0.3 percent of GDP, the same 1 percent decrease in government spending in GCC states improves their current account position by 1.2 percent of GDP.7

All in all, exchange rate reforms will only come gradually as long-term national objectives, including broader diversification, labor market nationalization, and financial market development and integration, are delivered. Any possible future transition toward more flexible exchange rate arrangements will be a consequence of structural economic changes in the GCC, not one of its causes. Eventually, these demands for change will also be supported by major international economic and geopolitical shifts, including the de facto floatation of the Chinese renminbi, the creation of alternative benchmarks and platforms for pricing and trading oil, and the development of a tri-polar or multi-polar global reserve currency system.

Reserve adequacy in the Gulf

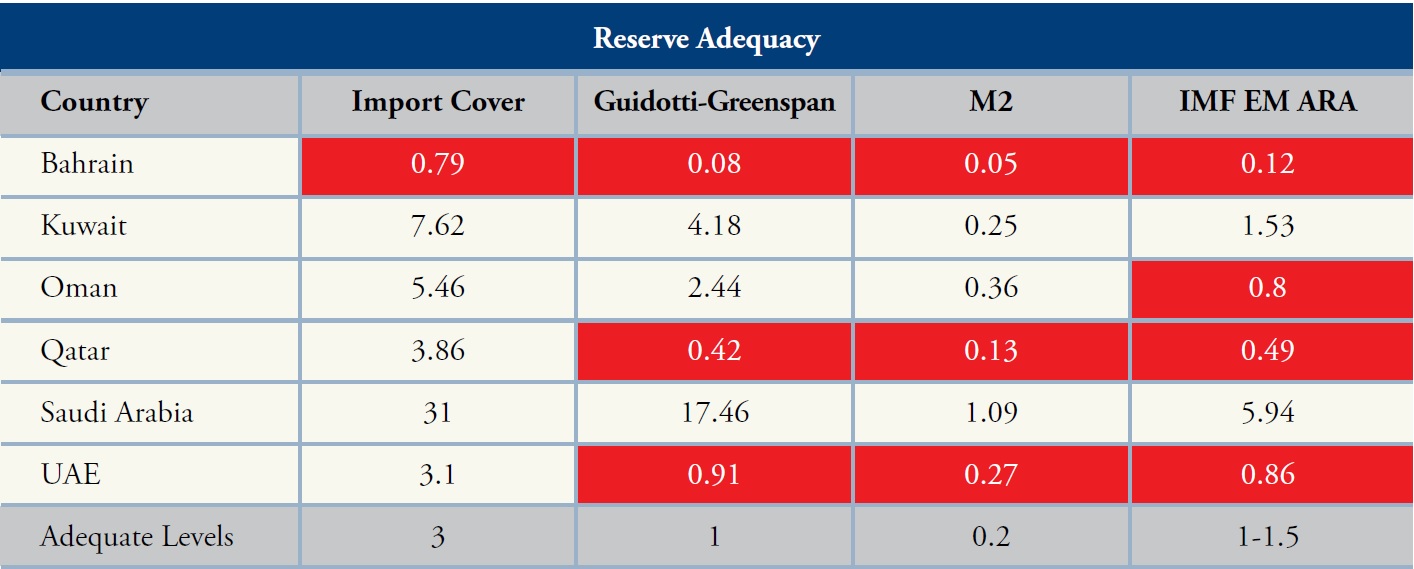

The above considerations make a strong case for GCC authorities to support their currency pegs. But, in the event of persistent imbalances and continued exchange market pressures, are they capable of defending them for long? One of the best ways to assess this is to use different reserve adequacy metrics to compare current and past situations with possible future scenarios.8Table I: Reserve Adequacy Metrics, October 2017

While most GCC states hold reserves that are well above the adequate import cover levels, the short-term debt to total reserves ratio (Guidotti-Greenspan), broad money to total reserves ratio (M2), and the IMF ARA EM metric show tighter realities. This is because market pressures in the GCC tend to be caused by current account deficits (export income risks) and capital outflows (capital flight risks).

The reserve adequacy analysis may lead us to conclude that Saudi Arabia enjoys the most comfortable position within the GCC. However, this is because the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA) operates both as a central bank and as a de facto stabilization fund (SF) and sovereign wealth fund (SWF). SAMA is officially in charge of investing even in less liquid assets through its investment portfolio.

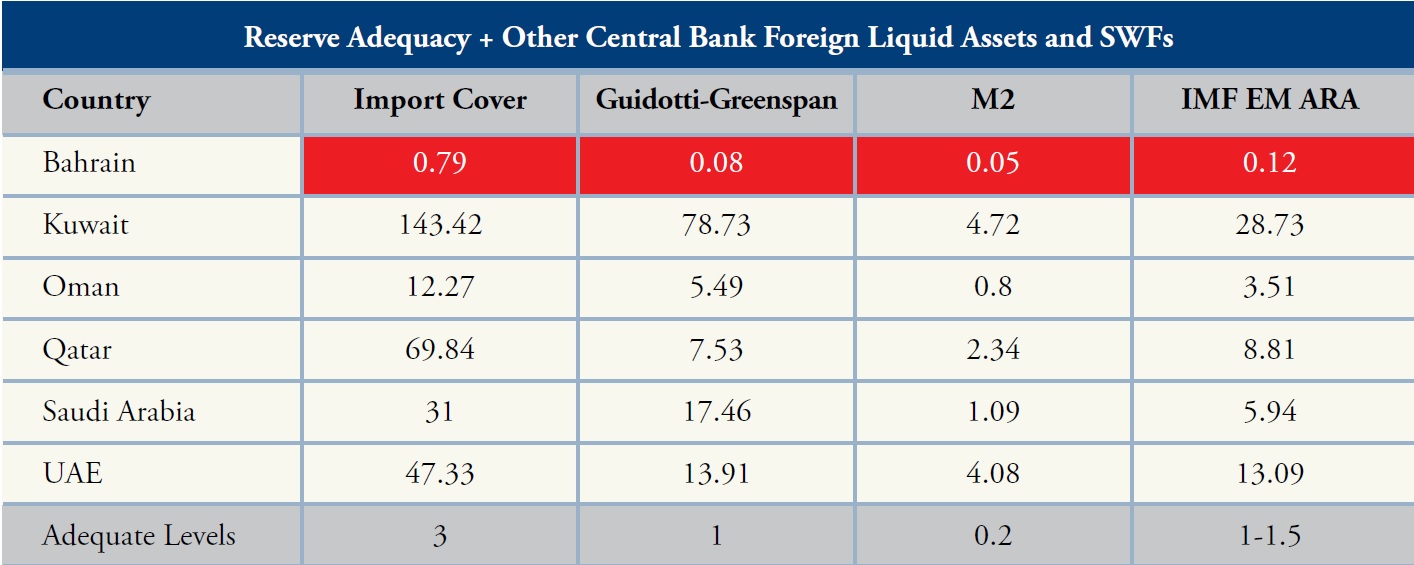

When you add SF and SWF assets under management to the reserve calculations, the position of the wealthier GCC states improves remarkably. In this case, Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE fare so well that their holdings become a large multiple of the adequate precautionary levels observed in Table II, and all countries but Bahrain hold sovereign foreign liquid assets that are well above historic lows in the 1980s and early and late 1990s.

Table II: Reserve Adequacy + Other Central Bank Foreign Liquid Assets and SWFs, October 2017

But including SF and SWF assets in calculating official reserves should be taken cautiously. Although few would oppose that these assets are available or can be made available to central banks and monetary authorities, not all assets are created equal and special attention should be paid to the varying compositions and levels of liquidity of different assets. In general, resources tied up in greenfield and brownfield physical projects (i.e. oil, mining, infrastructure, and real estate) or assets invested in other equities (i.e. private equity, hedge funds, and emerging markets) are not liquid enough for foreign exchange reserve management.

For example, Mumtalakat, the SWF of Bahrain, is believed to hold $10.6 billion in assets, but it is not included in Table II because those assets are overwhelmingly concentrated in a small number of illiquid Bahraini ventures and other GCC projects (78 and 20 percent of total assets, respectively), making them inadequate fiscal or financial buffers.9 Table II also excludes Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) because only 5 percent of its $230 billion in assets are believed to be held overseas.10

Overall, with the exception of Bahrain, reserve adequacy metrics indicate that the precautionary capabilities of the GCC are superior now compared to the early and late 1990s and 2000s. Since those states were able to sustain their petro-pegs even during more severe liquidity crunches, the fixed exchange rate regimes in almost all the GCC states can most likely be defended in the foreseeable future.

The peso problem and the currency forward market

However, one puzzle remains: if traditional metrics indicate that the five stronger GCC currency pegs are sustainable, why have the currencies of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Oman depreciated in the currency forward market? Forward rates reflect spot exchange rates on the maturation dates of forward contracts. Depreciations of forward rates generally represent a signal of market expectations about possible devaluations in the near future.

But in the case of the GCC currencies, the drops are largely due to the “peso problem”—a positive risk premium priced by market traders anticipating events that are possible yet infrequent and unlikely. “Peso problems” often occur when markets incorporate known extreme possibilities in asset prices. In the context of fixed exchange rates, “peso problems” inform how investors price unlikely devaluations and de-pegs. In other words, the recent spikes in forward rates do not reflect an increase in the magnitude of likely devaluations, but rather an increase in the probability of what is still seen as unlikely devaluations and de-pegs.

Reasons for greater probabilities of future exchange rate realignments and de-pegs abound largely due to political and economic realities in the GCC and the world economy. Concisely, they are associated with (i) the dynamics of country-specific factors (macroeconomic imbalances, political risks, and policy challenges), (ii) the interplay between heightened domestic political risks and regional geopolitical risks, (iii) long-run structural transformations in the supply side of global oil and gas markets, and (iv) long-term shifts in both international volatility and liquidity.

Safe despite the circumstances: The petro-pegs in Qatar and Saudi Arabia

While Qatar and Saudi Arabia are “safe” in terms of their precautionary financial buffers, Qatar faces additional liquidity challenges due to the ongoing GCC crisis and Saudi Arabia’s radical domestic reforms may create demand for exchange rate flexibility in the long term.

While Qatar and Saudi Arabia are “safe” in terms of their precautionary financial buffers, Qatar faces additional liquidity challenges due to the ongoing GCC crisis and Saudi Arabia’s radical domestic reforms may create demand for exchange rate flexibility in the long term. It is worth assessing how these developments affect the pegs in those two countries before analyzing the more vulnerable cases of Bahrain and Oman.

Qatar and the GCC crisis

When Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt severed diplomatic relations with Qatar and imposed a land, sea, and air blockade against the country on June 5, Qatar’s economy had to deal with a major financial shock. Over the first six months of the sanctions, Qatari banks faced $35.4 billion in capital outflows and its central bank witnessed a $21 billion drop in official foreign exchange reserves.11 But in the absence of new geopolitical shocks, the worst is behind Qatar in terms of both capital flight and deposit outflows. This is because most outflows were from the Qatari accounts of residents from blockading countries, and most bank liabilities to those citizens were short-term (less than six months) and have probably nearly all matured or been swapped and sold. Today, banks are operating normally and the cost of long-term credit to firms has increased a mere 5 basis points after the siege started.12

The government holds net financial assets of at least $331.1 billion or 203 percent of GDP, 87 percent of which is estimated to be held overseas or in hard currencies.13 This sovereign economic dominance was key to withstanding what would have otherwise been a major financial hit. Notwithstanding the blockade, economic factors commonly associated with a currency crisis or a devaluation are simply not found in Qatar. The country runs structurally large fiscal and current account surpluses and is able and willing to sustain the dollar peg with its external revenues and financial buffers (Table II).

Saudi Arabia’s historic moment

Sovereign economic dominance also marks Saudi Arabia. The broad Saudi public sector is estimated to hold $705.9 billion in net financial assets or 104 percent of GDP.14 However, Saudi Arabia is on the brink of a historic moment in which the leadership will have to cope with powerful demographic pressures, radical economic reforms, and the redesign of its power structure amid several proxy wars and conflict with Iran. When measured against these challenges, the financial wealth of the government becomes much less reassuring, especially while the country has been running fiscal and current account deficits of $213.2 billion and $76.7 billion as of January 2015.15

The Saudi political shakedown has so far produced mixed signals for markets (more willingness for reform but less predictability and less veto players to balance absolute power following the corruption clampdown and political purge). On the one hand, a financial shock is not excluded in case of future disruptions. On the other, the structural economic transformation of Saudi Arabia may accelerate. Over the long run, fiscal reforms, the IPO of Saudi Aramco, the strengthening of the PIF, and the construction of the dream city, NEOM, may produce diversification and create conditions in which exchange rate flexibility will be positive.16 In the meanwhile, there is enough room to withstand shocks and lengthen fiscal adjustments over reasonable horizons (Table I). Absent any black swans, Saudi Arabia should be able to defend its peg.

The vulnerable exceptions: The petro-pegs in Bahrain and Oman

In the more vulnerable economies of Bahrain and Oman, and in a somewhat self-fulfilling way, peso problems may increase the chances of extraneous events causing currency crises and devaluations. However, because of historical, economic, political, and financial links in the region, currency crises in Bahrain and Oman can have contagion effects across the GCC, forcing further devaluations or costing billions of dollars in reserve losses and bail-outs. Neighboring countries have an incentive to support those economies to avoid any currency events in the region. Bahrain and Oman are therefore likely to continue defending their currencies, despite their fiscal pressures.

Bahrain: The weakest link

Bahrain holds fiscal deficits of 15 percent and 14.67 percent of GDP and current account deficits of 3.1 percent and 4.7 percent of GDP in 2015 and 2016, respectively.17 Its foreign exchange reserves fell by 49 percent from $5.5 billion to $2.8 billion from June 2014 to November 2017.18 Bahrain has a limited capacity to borrow from non-residents since it has a high external debt-to-GDP ratio of 147 percent and its credit rating was downgraded from investment grade to high-yield or “junk” by Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch in 2016.19 The mass protests of 2011 and the following social and political instabilities have prevented the government from performing a fiscal retrenchment program. In fact, Bahrain is the only country in the GCC that increased government spending after the oil crash. It reportedly asked Gulf allies (Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) for financial support to maintain the peg.20

Although Bahrain has by far the tighter reality in terms of reserve adequacy, its strategic location and the Sunni-Shia/Saudi-Iranian regional proxy war form a scenario in which its small economy is simply “too important to fail.” The core countries of the GCC, and especially Saudi Arabia, are committed to providing political, institutional, and economic support to Bahrain in order to secure the regional geopolitical status quo. For a group that still holds approximately $2.8 trillion dollars in official reserves and relatively liquid sovereign assets, Bahrain’s $1.5 billion current account deficit and $4.6 billion fiscal deficit are minor issues.21Oman’s complicated regional ties

Oman is another weak link in terms of currency pegs in the GCC. The country ran at a fiscal deficit of 15.1 percent and 20.6 percent of GDP and current account deficit of 15.5 percent of GDP in both 2015 and 2016.22 Despite continued technical support from investment grade ratings and the unusual small drop of only 5.3 percent in the level of official foreign exchange reserves after the oil price crash, total gross foreign assets have declined by 24.7 percent and the debt to GDP ratio increased from 4.9 percent to 32.6 percent.23 Oman’s economic strategy relies on a mix of fiscal retrenchment, external and domestic borrowings, and drawing down on government deposits and other sovereign assets.

While total government expenditure declined by 12.4 percent between 2014 and 2016, additional fiscal tightening is likely to be limited by political constraints imposed by a non-traditional royal succession and the shadow of the 2011 Omani Protests. Moreover, non-reserve sovereign assets in stabilization funds and other special-purpose vehicles have declined by 47.75 percent.24 The Petroleum Reserve Fund, the Infrastructure Project Finance Account, and the Oman Investment Fund are nearly exhausted with $600 million in assets under management at the end of 2016 versus $11.5 billion in 2014.25 The State General Reserve Fund holds $18 billion in foreign assets, of which only around 50 to 70 percent are believed to be liquid.26 In the absence of more meaningful fiscal efforts and under the very dramatic scenario of no access to domestic or international debt markets and no reliance on onshore government deposits, financial buffers would be above precautionary levels for a period of only 6 to 7 months.

Moreover, Oman is affected by a more independent foreign policy stance in relation to other GCC states. Closer relations with Iran and a relative distance from Saudi Arabia’s regional initiatives make it more difficult for Muscat to benefit from non-conditional financial support from the region. Curiously, the regional dispute created by the blockade against Qatar may work in favor of Oman, which adopted a neutral stance to Qatar. The dispute may open-up the potential for increased Qatari financial support. Oman’s sizable fiscal and current account deficits are already generating speculations about alternative financing arrangements to sustain the peg, including possible support from countries like China.

Recommendations: Establishing Formal Liquidity Support Facilities

The situations of Bahrain and Oman suggest a need for regional self-help mechanisms aimed at preventing financial crises.

The situations of Bahrain and Oman suggest a need for regional self-help mechanisms aimed at preventing financial crises. In fact, the two countries are no strangers to direct or indirect financial support from the region. During the Arab Spring, the GCC states set up a $10 billion development fund dedicated to financing housing and infrastructure projects in Bahrain and Oman. The initiative was important for project development and potential output growth, but it did not address short-term liquidity and balance of payments problems. In the absence of regional liquidity support facilities, Bahrain and Oman would have to resort to opaque, ad-hoc negotiations in order to get short-term relief.

In a context in which GCC states are championing comprehensive structural reforms, including transparency and accountability in economic policymaking, obscure financial agreements are not the best possible solution to tackle currency crises. There are several successful international experiences involving the development of liquidity support facilities, including the East Asian Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) and the most recent unlimited bilateral swap networks between central banks of key advanced economies.

While intra-regional political differences make it difficult for the GCC to design and implement such cooperation projects, a more gradualist approach toward regional financial cooperation could start with bilateral arrangements to strengthen policy dialogue, information-sharing, coordination and, ultimately, liquidity provision. In fact, under the current GCC spat, a network of bilateral agreements would be the only politically acceptable option. Blocs of arrangements can include Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar, on one side, and Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, on the other.

A gradualist approach would start by creating bilateral surveillance and monitoring mechanisms under a shared authority of ministries of finance and central banks. Deputies from these institutions would gather twice a year on an informal basis to conduct mutual surveillance and design a permanent process of monitoring. Preferably, formal economic monitoring frameworks would be developed to provide early warnings of potential balance of payment crises or other relevant economic occurrences. Peer-review meetings and macroeconomic monitoring exercises would evolve toward the sensitive issue of exchanging data on short-term and medium-term capital flows. Such bilateral surveillance and monitoring mechanisms would foster policy dialogue and enhance confidence-building among the participants.

Over the medium-term, a network of bilateral swap agreements can be arranged with GCC states experiencing balance of payments problems. The two strong economies in each bloc (Kuwait and Qatar; Saudi Arabia and the UAE) can first sign “two-way” arrangements between themselves and then sign “one-way” arrangements with the weak country of their bloc (Saudi Arabia and the UAE can sign “one-way” arrangements with Bahrain, while Kuwait and Qatar can sign “one-way” arrangements with Oman).27

If the dispute drags on and the GCC is effectively made obsolete, the financial sub-blocs would increase in importance. When and if the parts ever agree to end the dispute and revive the GCC, the bilateral agreements can be gradually “regionalized.” Under this positive scenario, and in a somewhat similar way to what happened to the CMI, the network can evolve into a regional reserve pooling arrangement governed by a single contractual agreement. The efficiency gains provided by a network of swaps or pooled regional official reserves may help prevent currency crisis in the vulnerable economies and avoid potential contagion effects and credibility problems. Moreover, by facilitating statistical and regulatory harmonization and regional macroeconomic policy coordination, a GCC-based surveillance and monitoring mechanism and liquidity support facility would facilitate a renewed and realistic discussion about possible paths for a monetary union to be built in the future, should the GCC prove to be resilient and relevant.

Conclusion

Despite the macroeconomic challenges facing GCC states during this period of low oil prices and heightened geopolitical risks, we are unlikely to see any devaluations in the regional bloc. Fixed exchange rate regimes continue to be the optimal macroeconomic policy framework for the countries and devaluation is unlikely to alleviate their balance-of-payment challenges, which can be more effectively addressed through fiscal policies. Nevertheless, given asymmetries in terms of economic size, reserve adequacy and macro imbalances, some countries in the bloc, namely Bahrain and Oman, are more likely to resort to devaluing their currencies, despite the risks.

Yet, the economies of the GCC should not be assessed in isolation. A currency event in one state can have a contagion effect on others. While intra-GCC political and diplomatic disputes make regional support mechanisms less likely, bilateral and trilateral arrangements will have to step up to provide liquidity support to help countries like Bahrain and Oman defend their pegs. To effectively prop-up those weak economies, the countries of the region should look to develop formal structures of liquidity provision that include surveillance, monitoring, and data-sharing mechanisms to ensure the appropriate allocation of funds and build trust between those countries. Creating those formal structures would also help revisit the idea of further regional monetary and economic integration in the future.

-

Footnotes

- Numbers reflect the Brent crude oil spot price, a global benchmark price for crude oil. Data was obtained from Bloomberg, accessed January 9, 2018.

- Author’s calculation based on data from national central banks.

- Author’s calculation based on data from national central banks and monetary authorities, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) International Financial Statistics (IFS) and World Economic Outlook (WEO), sovereign wealth funds, and Haver Analytics; best estimates from the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute.

- Aasim Husain et al., “Global Implications of Lower Oil Prices,” IMF Staff Discussion Note, July 2015, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1515.pdf.

- Alberto Behar and Armand Fouejieu, “External Adjustments in Oil Exporters: The Role of Fiscal Policy and the Exchange Rate,” IMF Working Paper WP/16/107, June 2016, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/External-Adjustment-in-Oil-Exporters-The-Role-of-Fiscal-Policy-and-the-Exchange-Rate-43941; Dalia Hakura and Andreas Billmeier, “Trade Elasticities in the Middle East and Central Asia: What is the Role of Oil,” IMF Working Paper WP/08/216, September 2008, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Trade-Elasticities-in-the-Middle-East-and-Central-Asia-What-is-the-Role-of-Oil-22325.

- Hakara and Billmeier, “Trade Elasticities in the Middle East and Central Asia,” 16.

- Behar and Foeijieu, “External Adjustments in Oil Exporters,” 26.

- Reserve adequacy metrics used in this study include (i) import cover, (ii) Guidotti-Greenspan, (iii) M2, and (iv) the IMF ARA EM metric. Import cover stands for the ratio of reserves to months of imports. The adequate threshold for import cover is three months. The Guidotti-Greenspan rule states that a country should hold an equal number of reserves to short-term external debt (up to one-year maturity). The M2 metric assesses the ratio of reserves to broad money (M2). The IMF ARA metric is a composite that includes export revenues, broad money, short-term debt, and portfolio liabilities.

- Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute best estimate as of September 2017; Saeed Azhar and Hadeel Al Sayegh, “Update 1-Bahrain Wealth Fund Mumtalakat Has up to $300 Mln for New Deals -CEO,” Reuters, June 14, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/mumtalakat-investment/update-1-bahrain-wealth-fund-mumtalakat-has-up-to-300-mln-for-new-deals-ceo-idUSL8N1JB2V1.

- Eric Schatzker, Matthew Martin, and Arif Sharif, “Saudi Wealth Fund Plans to Borrow to Double Investment Returns,” Bloomberg, October 25, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-24/saudi-sovereign-fund-to-use-borrowings-as-it-targets-9-return; the 5 percent estimate is based on information taken from the PIF investment program. See PIF, “The Public Investment Fund Program (2018-2020),” http://vision2030.gov.sa/en/pifprogram/about.

- Author’s calculation based on data from the Qatar Central Bank, including the bank’s monthly statement, monthly monetary bulletin, and quarterly statistical bulletin.

- Ibid.

- Net financial assets are based on author’s calculation of data from the Qatar Central Bank and an estimation of the total value of QIA’s domestic ($100 billion) and foreign assets ($200 billion). The estimation is based on official statements made during the transfer of QIA’s domestic portfolio to the oversight of the Ministry of Finance in March 2017 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-03-22/qatar-said-to-move-100-billion-portfolio-to-finance-ministry). The figure is aligned with the authors’ estimation based on the expected market value for Qatar Airways and Qatari Diar and the market value of QIA’s stakes in local companies listed on the Qatar Stock Exchange; GDP based on IMF’s estimation for 2017. See IMF, “Seeking Sustainable Growth: Short-Term Recovery, Long-Term Challenges,” World Economic Outlook, October 2017, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2017/09/19/world-economic-outlook-october-2017.

- Author’s estimation and calculation based on data from the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, and the IMF.

- Author’s calculation based on data from the Ministry of Finance and the SAMA.

- NEOM stands for “New Mostaqbal” or “New Future” and is a planned megacity and special economic zone being designed by the government of Saudi Arabia along its western coast, where it expects to have over $500 billion invested to develop a tourism and innovation hub.

- IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2017.

- Author’s calculation based on data from the Central Bank of Bahrain.

- Moody’s Investor Service, Sovereigns – Gulf Cooperation Council: Currency risks still low on average, but rising in Oman and Bahrain (March 14, 2017).

- Shahine, Alaa and Zainab Fattah, “Bahrain Asks Gulf Allies for Aid to Stave off Crisis,” Bloomberg, November 1, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-01/bahrain-is-said-to-ask-gulf-allies-for-aid-to-stave-off-crisis.

- Author’s estimation and calculations based on data from central banks and monetary authorities as well as, when not otherwise available, best estimates for SWFs’ total assets under management from the IMF and the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute.

- Author’s calculation based on data from Central Bank of Oman.

- Standard & Poor’s cut Oman’s credit rating to “junk” or high yield in May 2017, but Moody’s and Fitch are still granting the investment grade for the sultanate; author’s calculation based on data from the Central Bank of Oman and Haver Analytics

- Author’s calculation based on data from the Central Bank of Oman.

- Data from Haver Analytics.

- Data from Haver Analytics; assumption made according to the SGRF’s investment profile presented in their last annual report in 2016. See State General Reserve Fund, Building a sustainable future for Oman: annual report 2016 (Muscat: SGRF, 2017). https://www.sgrf.gov.om/frontend/web/uploads/8550279-sgrf-annualreport-2016-eng.pdf.

- Under “two-way” arrangements, parties are both potential borrowers and creditors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).