Gender-based wage gaps are ubiquitous in U.S. labor markets, even in occupations where women make up most of the workforce. This dynamic extends to the K-12 educator workforce, where women account for roughly three quarters of the teaching workforce but make an estimated $5,000 less than men annually, based on a 2019 study using nationally representative data.

How does such a large gender gap in earnings arise in an occupation in which uniform salary schedules are used in the vast majority of school districts? Though gender-based inequalities in teaching are smaller than what we see in other occupations, they’re still worrisome and compel us to dig deeper into this issue. We wish to both better understand where wage gaps come from and what policymakers can do to mitigate them.

New study documents gender wage gaps among teachers

In recognition of Equal Pay Day, this policy brief summarizes the findings of our recent study investigating gender wage gaps among public school teachers. In our study, we used survey data from the National Teacher and Principal Surveys. Our analysis provides unique insights into the different sources of school-based income for teachers. Further, the data allows us to disentangle labor supply (e.g., teachers choosing to perform extra work) from employers’ decisions to compensate them for their labor.

“This means a 7% bonus paid to women only would be needed to fully equalize pay between genders, based on reported earnings in our sample.”

Overall, we find raw gender wage gaps of about $4,000 favoring men when combining all sources of teachers’ income from schools (using 2017 dollars). This means a 7% bonus paid to women only would be needed to fully equalize pay between genders, based on reported earnings in our sample. These gaps arise from differential compensation occurring both in base salary and in supplemental compensation teachers earn from schools.

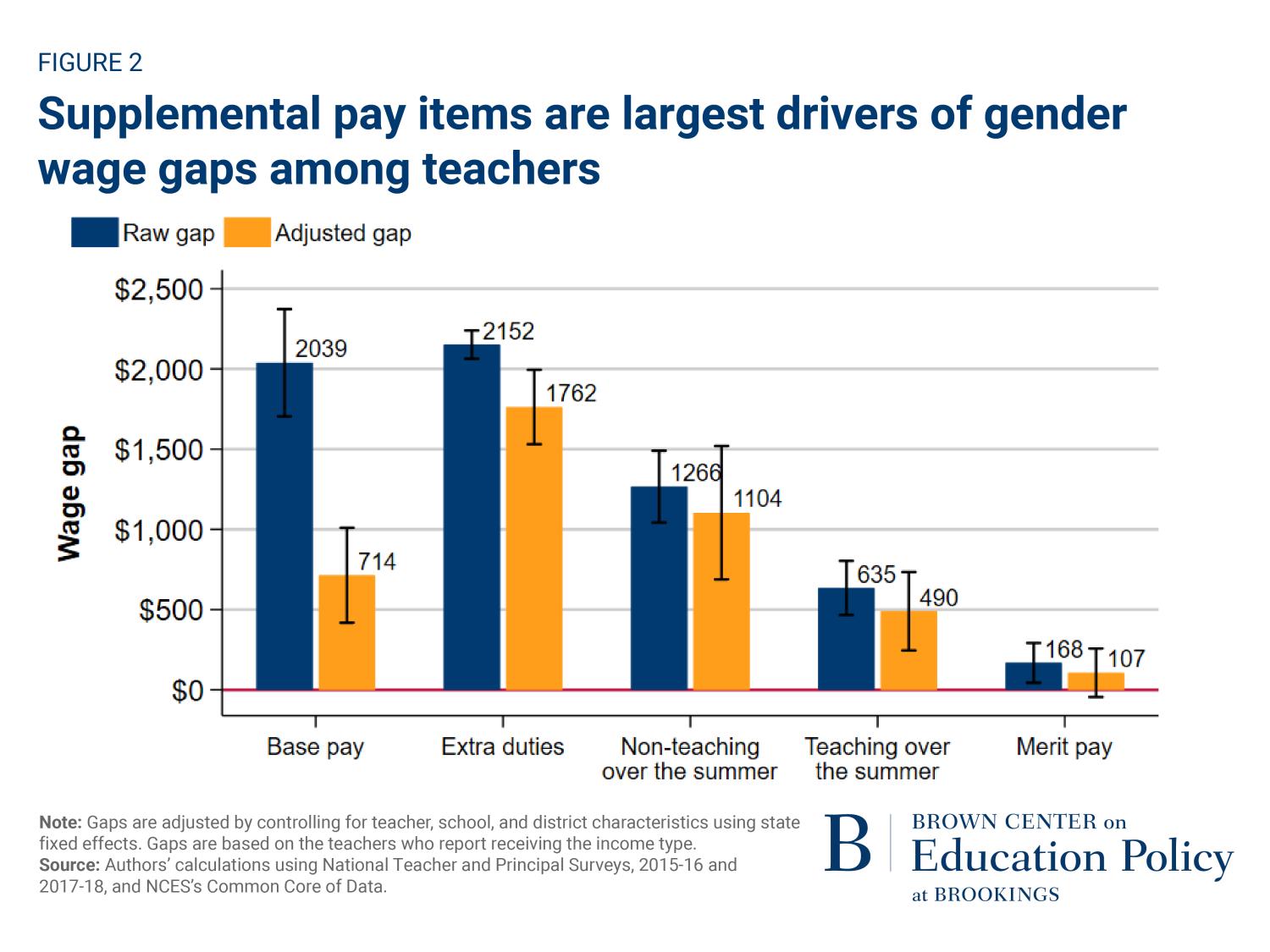

Gender wage gaps narrow when we control for observable teacher and school characteristics, though a difference of roughly $2,200 remains—estimated to be $714 in base pay, $1,204 in extra duty pay, $180 for a non-teaching job over the summer, $80 for summer teaching, and $0 for merit pay, on average across all teachers. Importantly, our regression models cannot readily account for most of the gender gap in teachers’ income based on extra work within the school. We show men tend to be modestly more likely to participate in this extra work and are much more likely to be paid for it, especially if their school principal is also a man. Taken together, this evidence suggests these supplementary payments are more likely to reflect gender-based discrimination in comparison to base pay.

We develop these findings below, and in the paper, we explore many facets of these wage gaps that we omit here for brevity. In summary, we conclude that these wage gaps are real and pervasive across many settings (e.g., contract restrictiveness, union strength). We argue these gaps warrant policy interventions to mitigate them, and we close with a discussion of potential policy solutions.

Factors that contribute to gender wage gaps

Gender wage gaps can arise for many reasons, and it’s important to try separating out their underlying causes. These causes dictate whether policy action is warranted to address these gaps. For example, gaps due to women’s personal choices to work less after school hardly merit a policy response, though a response is warranted if men are getting paid more than women for the same after-school work. This section reviews prior research on the varied factors behind wage gaps, with a focus on where discrimination is likely to occur among teachers.

Wage gaps could arise because of differences in women’s characteristics or choices— what economists refer to as labor supply factors. For example, women may possess fewer qualifications tied to pay, may choose to work less, or may prefer jobs in lower-paying settings or assignments. Differences in these dimensions are primarily driven by different choices women make within the labor market (relative to men), and thus are unlikely to be due to discriminatory employment practices. For example, men are widely documented to sort into more competitive environments and have higher toleration of failure than women, and these personality differences lead men to systematically sort into settings that pay more or where performance influences pay. Indeed, prior research has shown teachers apparently sort across district employers consistent with these patterns.

Wage gaps could also reflect differences in labor demand (i.e., from schools employing teachers). For example, employers might pay men more or assign men to tasks that provide more compensation. Employers who show differential treatment of male versus female employees meet the classical definition of employment discrimination. Prior experimental evidence using resumes has shown hiring managers often perceive women (especially mothers) as being less committed to work and associate men with breadwinner status; both perceptions drive managers to systematically favor men when determining pay. Similar discriminatory wage practices could occur among teachers—even with salary schedules in place—if districts reward male teachers with unearned teaching experience, for example, without giving the same to women.

Finally, the collective bargaining context in which teachers are employed merits close consideration. Though salary schedules are commonplace across all states, the bargaining power of teacher unions and the influence they have as an intermediary of the employer-employee relationship varies considerably both across states (based on collective bargaining laws) and within states (based on union strength). Unions claim that a strong union and collective bargaining protect teachers from arbitrary staffing decisions from administrators, ensuring fair wages and benefits. Many studies have considered how teacher salaries and education spending are influenced by union power. Yet, we know of only two studies that have engaged with the question of how union strength influences gender wage gaps for teachers, both of which find unions associated with smaller gender gaps.

Analysis

Our analysis provides new insights into how gender wage gaps manifest among teachers. In this section, we briefly describe our methodological framework and then present three key findings that emerge.

Methods

The National Teacher and Principal Surveys are nationally representative and collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). We use results from the 2015-16 and 2017-18 school years (the most recent data available). Our analysis sample consists of all respondents who are teachers employed full and part time in K-12 public schools. We also use collective bargaining agreement context information from the National Council on Teacher Quality and extract supplemental data on school characteristics from the NCES Common Core of Data.

Our methodology is primarily descriptive. We calculate mean differences in men’s and women’s reported earnings, across school-based income sources reported in the surveys (inflation –adjusted to 2017 dollars). We analyze five distinct school-based income sources: base pay, summer school pay (teaching and non-teaching summer jobs separately), merit pay, and taking on extra duties (e.g., leading an extracurricular activity). Reported earnings from sources outside of school are not considered in our investigation, though prior work indicates such income can be important, especially for men. We then adjust teachers’ compensation by using regression models that control for teacher demographics, qualifications, assignments, school and district characteristics, and state fixed effects.1 Adjusted gaps reported in this brief represent the mean differences between men and women after applying these regression adjustments.

Our analysis also comes with some limitations. Because this is self-reported data, we cannot account for differences in reporting errors between men and women. Also, we observe only reported pay differences, not inequalities in hiring decisions or job access, which may indirectly contribute to teachers’ earnings differentials. Additionally, our estimates could be influenced by teacher characteristics not included in our data that sort male teachers into schools with higher salaries.

In the sample we use for the analysis, we see only negligible differences between men’s and women’s prior teaching experience, education, and license credentials—all of which are typical salary determinants for teachers. Yet, we see large gender differences in subject specialization, which could lead to men earning more money for filling harder-to-staff positions (e.g., men are more likely to teach in secondary grades). These subject area differences can contribute to unadjusted gender wage gaps, though in our analytical models we control for these differences and hence “explain” part of the gap. Further, meaningful shares of our observed wage gaps are explained by either state- or district-level variables, consistent with the notion that teachers’ sorting patterns across different geographical areas contributes to the unadjusted wage gaps. However, meaningful large gender wage gaps persist even within the same districts after adjustments.

Our analysis is motivated, in part, to identify any differential treatment by gender. We cannot directly observe unfair behavior with our survey data, though we attempt to uncover differential employer treatment in two ways: uncompensated extra work and differential treatment by a male principal. The results we present below suggest employee discrimination is partially responsible for the gender wage gaps we observe, at least in supplemental compensation.

See how much of a difference gender makes in teachers’ paychecks. Manipulate the drop-down boxes along the top of the figure to see how the range of male and female teacher earnings changes for teachers with different qualifications and demographics.

Finding 1: All school income sources show gender wage gaps; most troublesome in extra duty pay

We observe unadjusted wage gaps favoring men exist in all income categories (see Figure 2, blue bars). When adjusting wages by a variety of individual, teaching assignment, school, and state differences, estimated gender gaps across all income sources narrow, though to varying degrees (yellow bars). The sizes of the adjustments are themselves meaningful, as they represent observable teacher differences that can be reasonably explained, including the labor supply differences described above. For example, the raw gap in base pay is $2,039, similar to the gap in extra duty pay. Though after controlling for all observable factors, the gap in base pay shrinks by nearly two thirds (to $714), suggesting most of the original pay gap is explained by gender differences in labor supply (e.g., men working in higher-paying assignments or contexts).

Gaps that remain after these adjustments are much more likely to be suggestive of discrimination, which we primarily observe in compensation from other sources. The bars for extra duties and non-teaching summer work, for example, do not shrink nearly as much in the regression adjustment and are estimated to be over $1,000. The estimated gap in merit pay is no longer statistically significant after these adjustments.

Finding 2: Differential compensation in extra duty pay suggests discrimination

We cannot directly observe unfair compensation practices among the survey responses, as we discussed above. Despite this limitation, we look for evidence of unfair practices empirically by aggregating across survey respondents and detecting patterns that arise consistent with theoretical predictions about how they could manifest. We look for these differences in two ways, both of which point to the presence of unfair pay practices among teachers.

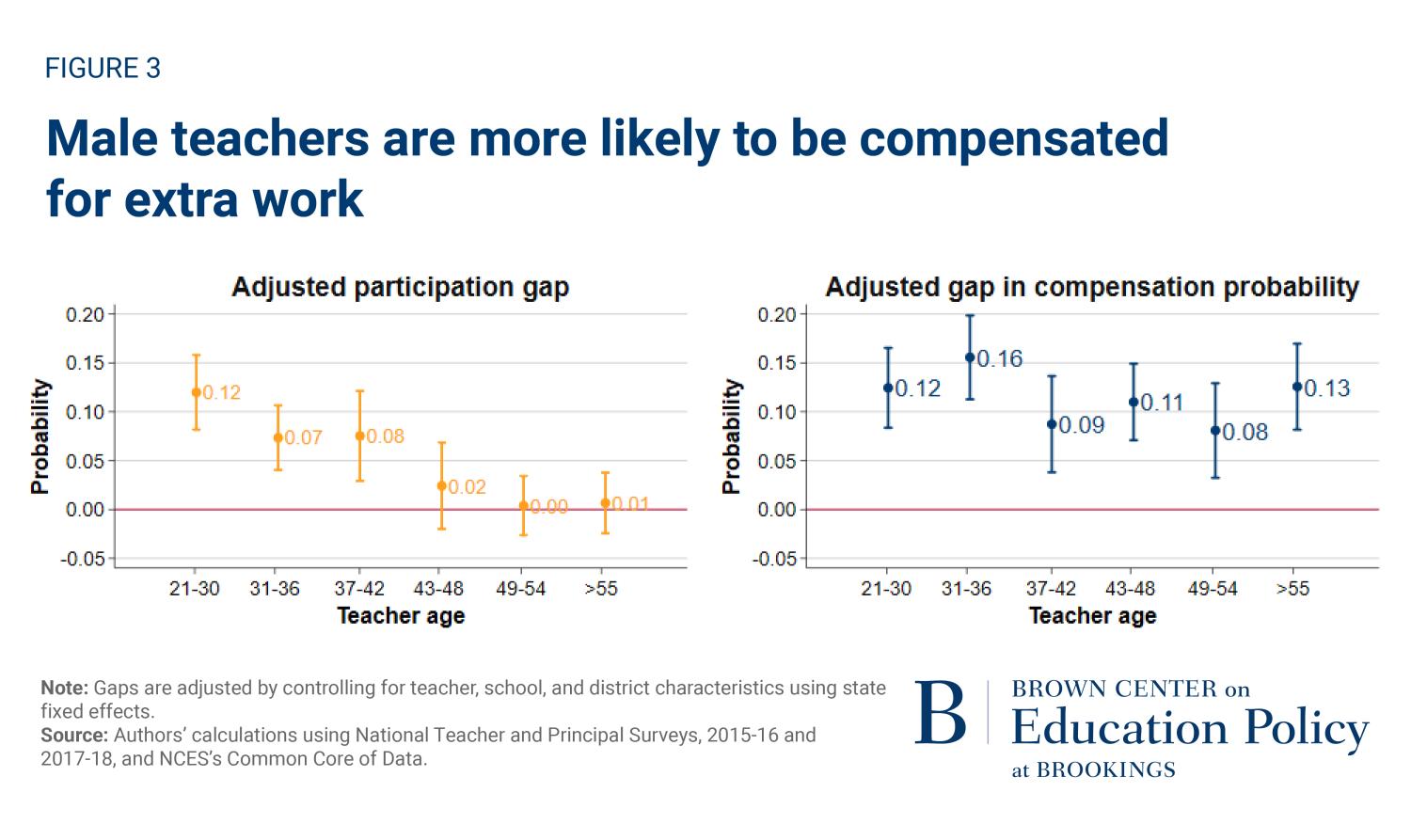

First, we look at participating in uncompensated extra work. One of the survey waves (the 2015-16 collection) gathered data on both those participating in extra duties beyond their base salary and those getting paid for them. Though most teachers (82%) report participating in these activities, less than half (44%) are paid specifically for the effort. As illustrated in Figure 3, men are both more likely to report participating in these tasks (on the left) and to report being paid for them, conditional on doing them (on the right). Notably, we estimate these differences at different teacher ages (along the x-axis of both panels) and find statistically significant gaps in participation during teachers’ 20s through early 40s. For example, male teachers are 12 percentage points more likely to participate in extra duties than their female peers when they are 21 to 30 years old, and seven percentage points more likely when they are 31 to 36 years old. This also happens to coincide with ages when women’s fertility peaks and they often have young children in the household. After having kids, women normally take on a larger share of household responsibilities than their male counterparts. Thus, we suspect caregiving activities are the most likely difference in explaining the gendered differential in labor supply we observe during these ages.

However, these differences in labor supply do not explain the gendered difference in the likelihood of being compensated for the extra work shown in the right panel—which shows up consistently and in similar magnitudes across all ages. Similar patterns of women disproportionately performing extra work (often uncompensated) to support employer needs are also observed among college professors and in laboratory settings.

“Across the different income types reported here, male teachers show an increase in their probability of receiving payment for their extra work when they have a male principal.”

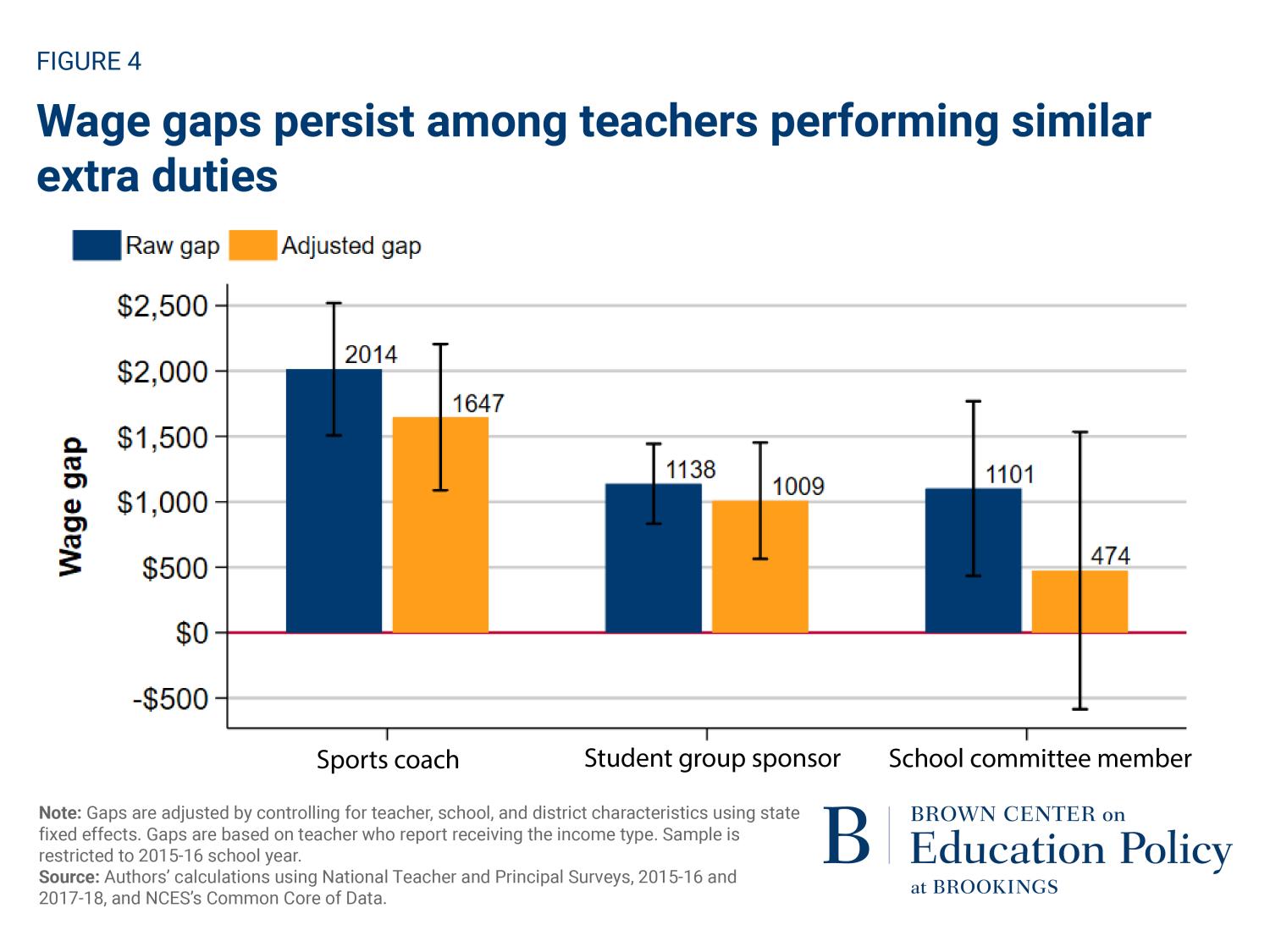

Note that this figure does not include actual wages, but simply whether teachers get paid for the extra work they perform. It is hypothetically possible that male teachers systematically take on more demanding jobs (with corresponding pay), while women take on less demanding jobs (with low or no pay). Therefore, differences in hours worked could explain observed gaps in supplemental compensation. Our investigation, however, suggests this is unlikely as even among those performing similar duties, wage gaps are evident. Figure 4 below shows the differences in compensation between male and female athletic coaches, student group sponsors, and school committee members. Overall, we find that male coaches and student group sponsors are paid more than their female counterparts with similar characteristics, earning $1,647 more and $1,009 more respectively. For school committee members, we find no wage gap once we adjust for observable characteristics. We also explored whether differences in the number of hours worked could be driving these earning differentials. The change in the magnitude of the gap is negligible when we account for reported hours worked, suggesting that the supply of labor does little to explain the earnings gap between these groups of teachers.

Next, we look to see whether wage gaps are sensitive to the gender of the school principal. Our investigation here is motivated by prior work uncovering differential principal treatment of teachers by race and gender. Figure 5 is an interactive data visualization that reports the differential likelihood for men to report income by type (on the left axis) versus the reported extra pay (on the right axis), when estimated separately by principal gender. Across the different income types reported here, male teachers show an increase in their probability of receiving payment for their extra work when they have a male principal. The change in the value of the adjusted gender wage gap varies across income sources, with extra duty pay seeing the largest bump favoring men. These compensation decisions that favor male teachers under male principals’ supervision may point towards preferential employee treatment. Recent research has found male teachers are more likely to leave a school if a principal is female and tend to sort to schools led by men. Our findings suggest that differential compensation could be a potential driver of these mobility patterns and likely help to prop up the gender wage gaps we observe.

Use Figure 5 to explore the differences in compensation likelihood and amount for male and female teachers under principals of different genders.

Finding 3: Gender wage gaps shape-shift depending on the union context

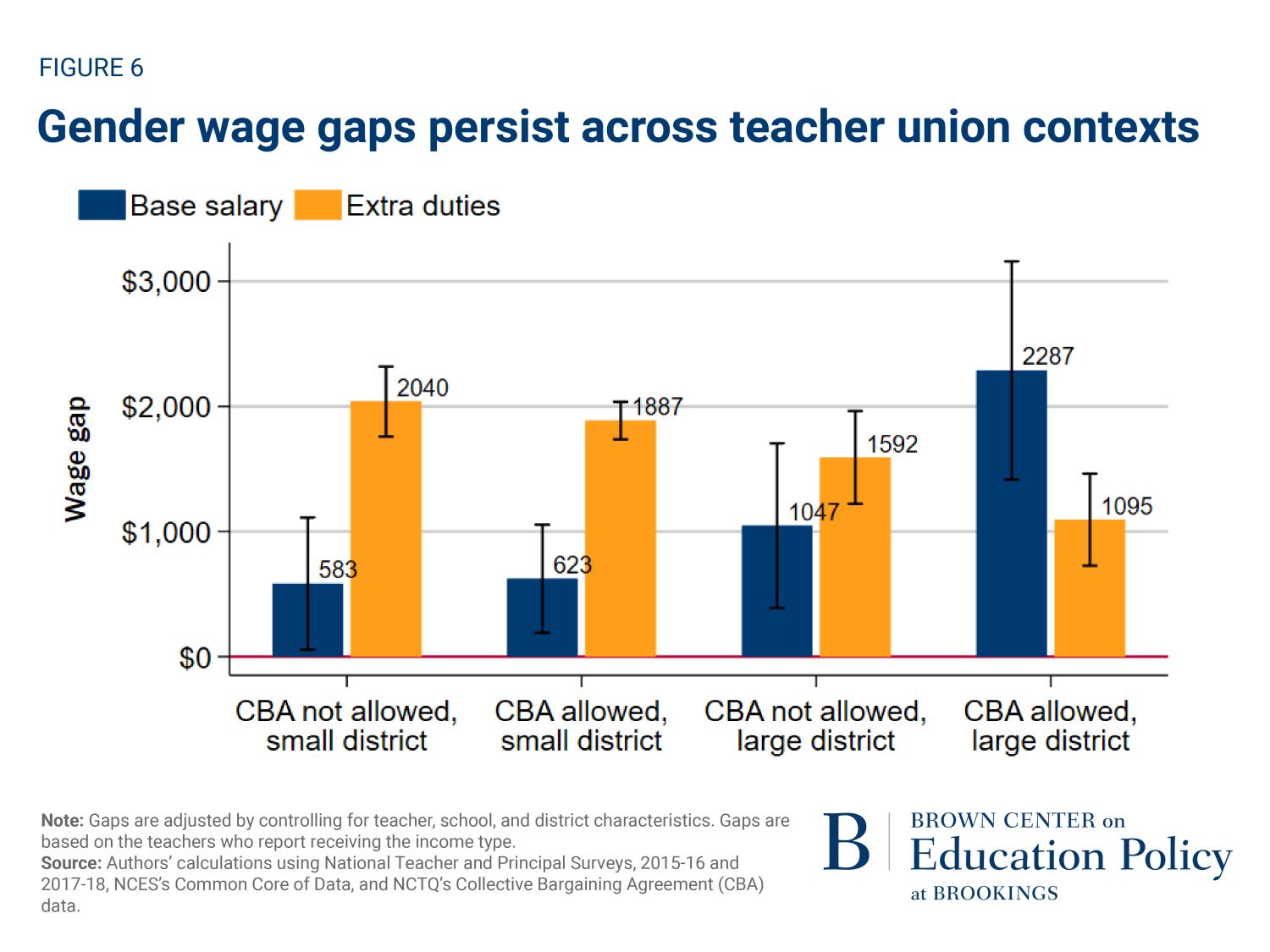

Finally, we investigate how the collective bargaining context and union strength might influence gender wage gaps. We combine the state’s collective bargaining regime (whether collective bargaining agreements, CBAs, are permissible or not) with a variable on district size to serve as a proxy for union strength and more restrictive contracts for employers. Prior work on the strength of teacher unions finds district size to be an important predictor of contract restrictiveness. This categorization results in four categories of union strength: small districts in non-CBA states, small districts in CBA states, large districts in non-CBA states, and large districts in CBA states.

Results from this investigation, presented in Figure 6, show that gender wage gaps are present in all the various categories, though they manifest differently across contexts. Small districts in non-CBA states (where we expect union influence on the contract to be lowest) have large regression-adjusted gender wage gaps in extra duty pay and relatively smaller wage gaps in base pay. Conversely, large districts in CBA states (highest union influence) have small wage gaps in extra duty pay but comparably larger gaps in base pay. In other words, the results suggest gender wage gaps favoring men are present in all settings, though the method through which men receive their extra pay systematically differs across collective bargaining contexts. The data do not allow us to say why, for example, wage gaps are higher in base pay versus extra duty pay in places we expect union influence to be strongest; future work is needed to understand the reason for the development of the gender wage gap in this dimension.

Policy discussion

Male teachers earn $2,200 more than female teachers of similar contexts and with comparable qualifications. These gaps are small by comparison to other professions but warrant policy attention since teachers are government workers and constitute one of the largest professions in the country. Other public workers have similar wage gaps: A study from the Government Accountability Office shows that the estimated unexplained wage gap among federal workers has remained relatively constant throughout the last two decades, suggesting that unobservable factors (including potential discrimination) continue to thwart progress toward equal pay.

Historically, government workers have been some of the first to implement policies aimed at improving gender and racial differences in employment and compensation. Notable examples include the adoption of equal-pay policies (at least on paper) for New York City teachers in 1912. The fact that we see these wage gaps persisting more than a century later, despite the dominance of the salary schedules that arose from these equal-pay policies, is evidence that more remains to be done to close these gaps. If we desire public workers, including teachers, to lead the way on closing gender wage gaps, what tools can be used to help equalize wages? We consider potential solutions in this section and offer commentary about their likely success among teachers (ordered from most to least promising).

A fact sheet produced by the National Women’s Law Center details recently enacted legislation geared towards reducing the gender wage gap, which offers several possible solutions. Other ideas are drawn from the education literature. Though many of these measures are still largely experimental, and thus their efficacy is not well vetted, we will be drawing on available evidence both inside and outside education settings to contextualize their feasibility for reducing wage gaps among teachers.

Before considering possible solutions, we should briefly recognize the biological and cultural context that contributes to the staying power of these wage gaps. On the biological side, women’s fertility peaks during the same ages in which individuals are typically developing human capital and their career trajectories. Women stepping out of the workforce temporarily for childrearing during this period of career development is frequently cited as a major contributor to gender wage gaps—not just for the duration of the pause but for years afterwards. The reason for the permanence of the childrearing penalty, however, bleeds into the cultural side of the ledger as childcare responsibilities among parents continue to fall heavily on women’s shoulders and persist for years while children live at home (patterns that were exacerbated during the pandemic). Further, as discussed above, women tend to express personality traits that serve to decrease women’s wages in comparison to men’s: less competitive, lower willingness to tolerate failure, and more agreeable. These gender differences are presumably the result of cultural, rather than biological, forces shaping women’s roles and dispositions in ways that combine to disadvantage them in the labor market. Thus, even though we discuss policy solutions intended to close gender wage gaps among teachers, we must recognize that full equality will likely require change in these cultural contexts, too.

“Requiring school districts to regularly collect and report high-level patterns in payroll data, with a focus on gender equality, will bring transparency into payroll spending.”

Increased pay transparency

Gender wage gaps occur in districts, so district-level payroll practices could be a promising avenue for countering them. School districts are often large bureaucratic entities that process many thousands of transactions annually, obscuring how individual payments contribute to inequalities. Requiring school districts to regularly collect and report high-level patterns in payroll data, with a focus on gender equality, will bring transparency into payroll spending. Further, districts could create policies governing supplemental pay that articulate a common set of criteria. For example, a district-wide policy that prescribes extracurricular sponsors’ expected qualifications, skills, duties, and compensation could reduce the opportunity for preferential treatment. A new study found that the implementation of pay transparency systems in academia narrowed gender pay gaps over time, suggesting that increasing transparency is a promising tool to level the playing field among teachers.

Strengthening collective bargaining agreements to include supplemental compensation

Some practices already utilized in schools could be modified or strengthened to mitigate gender wage gaps, and we believe more explicit language in collective bargaining agreements could be a part of the solution. For example, gender wage gaps increased among Wisconsin teachers in the wake of recent changes to state bargaining laws, suggesting their role in equalizing pay. Our report shows that the largest driver of gender wage gaps among teachers is compensation for extra duties ($714 for base pay vs. $1,762 for extra duties), and The National Council on Teacher Quality reports that only six states mandate this category of pay to be included in CBAs. Broader inclusion of supplemental duty pay in union contract negotiations may consequently narrow the gender wage gap among teachers. Note, however, that even while we found lower wage gaps in extra duties in stronger union contexts, we also found higher gaps in base pay. Unions (and districts they are negotiating with) should try to close opportunities for gender wage gaps through all compensation pathways simultaneously to avoid payments that simply shape-shift to fit new contract constraints.

Salary history bans

A salary history ban prohibits employers from accessing information about a new hire’s past compensation when determining their pay. In theory, if a worker has been unfairly compensated in the past, then using salary histories would perpetuate gaps across employers; though opponents argue productivity-related differentials will also be lost in implementing bans. Salary history bans, whether in public jobs only or across all occupations, have been implemented in a growing number of states since 2017. Some evidence on the effectiveness of banning salary histories points in the direction of reducing the gender wage gap, though the effect seems to be targeted to new hires and job changers. Other work concludes that salary history bans narrow gender wage gaps in the private sector. With this evidence, we suspect salary history bans for teachers may help, especially in settings where individual bargaining is less constrained. Adopting bans covering supplemental pay may also reduce gaps on the margin and merits further exploration.

Participatory budgeting

Since district or school leaders have high leverage in contributing to gender pay gaps, changes in budgeting practices may also reduce payment differentials. Participatory budgeting is a relatively novel approach to budgeting, where members of the community offer input on how to allocate a portion of a public institution’s budget, with recent examples including schools. Schools can invite parents, community members, and teachers into the decision-making process, offering input into what types of after-school work should get compensated (and how much). This process should steer spending decisions towards the community’s benefit and may mitigate biased salary allocations otherwise determined by a single school leader (e.g., paying excessive compensation for male coaches). We know of no evidence of participatory budgeting’s effect on wage gaps, though the importance of supplemental payments off the salary schedule leads us to believe that this could be an effective lever for narrowing gaps among teachers. The extent to which this policy lever reduces wage gaps would depend on how much discretion principals have over their budgets, and districts could adopt more participatory budgeting in settings where principals’ discretion is limited. We encourage future work to explore budgeting practices and their interaction with community-level input.

Paid parental and family leave

This is a common policy lever used to advance gender equity broadly. To our knowledge, very few school districts offer paid parental leave to their employees, and our findings show female teachers are less likely than men to participate in extra duties during their prime childrearing years. Providing more generous and equal parental leave for male and female teachers could potentially reduce the gender wage gap through equating labor supply by reducing the supply of male teachers. For example, an evaluation of the short-term effects of the introduction of paid parental leave legislation in California during 2004 found the law increased the likelihood of the father taking leave during their child’s first year by nearly 50%. Yet, these changes in male labor supply were temporary and strongest at the birth of the first child. Another study examined the same leave policy focusing on mothers’ employment and found an 8% reduction in their earnings six to ten years after giving birth, which suggests long-term increases in wage gaps. Based on this evidence, we are pessimistic about the use of paid family leave as a mechanism for reducing gender wage gaps. Of course, this policy may offer important benefits and support for teachers as they balance family and work responsibilities, but we see little reason to believe they will permanently narrow gender wage gaps.

Gender wage gaps influence pensions

Finally, we must acknowledge that compensation policies feed into pension systems. Hence, gender pay gaps are made permanent in retirement through pension plans. Gender differences in retirement preparation and assets is a growing area of public concern, and the teacher workforce is not immune. A 2018 study focusing on Nevada teachers finds that disproportionately female teachers included in state employee retirement plans generally subsidize the pensions of higher-paid, disproportionately male workers from other occupations. Given the unequal promotion of male teachers into higher-paying administration roles, even if education pension systems were isolated from other government occupations, large pension gaps would still persist. Teacher pension plans in most states have many shortcomings, as prior analysts have reported, including inflexibility and insufficient funding. A full discussion of pension reform ideas is beyond the scope of this brief, though we want to elevate how gender earnings gaps may be perpetuated through pension policies.

“Gender wage gaps persist among teachers, with male teachers earning $2,200 more than female teachers of similar characteristics. Supplemental school-based compensation plays a lead role in these gaps.”

Conclusion

Gender wage gaps persist among teachers, with male teachers earning $2,200 more than female teachers of similar characteristics. Supplemental school-based compensation plays a lead role in these gaps. Average male teachers earn $1,700 more in extra duty pay than their female colleagues with similar qualifications and in comparable contexts. We also find a gender gap in the likelihood of receiving payment for performing extra duties and being compensated for them. Men are even more likely to be paid for this extra work when the principal at the teacher’s school is male. These income sources off the salary schedule provide the most likely avenue for gender-based wage discrimination among teachers. Our results are in line with prior work examining wage gaps among principals both at the national and state level.

“…we argue that increasing pay transparency and including supplemental pay in collective bargaining agreements have the most potential to achieve pay equality.”

We then explore the potential of a battery of policies to reduce the gender wage gap. Among these, we argue that increasing pay transparency and including supplemental pay in collective bargaining agreements have the most potential to achieve pay equality. Additionally, salary history bans and participatory budgeting hold promise and warrant further exploration. We note that this report reveals areas where gender discrimination may be taking place among teachers, not whether a discriminatory act has occurred. Further research, particularly audits, would be useful in exposing these instances.

Teachers are critical for many reasons, including their influence on students. They deserve to be adequately compensated for the work they do leading our nation’s classrooms, regardless of their gender.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hana Dai and Melissa Carmona for excellent research assistance, as well as Jason Grissom and Jon Valant for providing thoughtful feedback on this brief.

-

Footnotes

- Explanatory variables include the following: teacher age, race, experience, certificate status, advanced degree, subject specialization, part-time status, number of contract days, the share of students eligible for subsidized lunch service, per-pupil expenditures, and district enrollment. The adjusted results include state fixed effects, removing any variation that occurs across states. We also tested the results using district fixed effects to account for teacher sorting and differences in contracts or cost of living across districts; the differences in the results were negligible. See the paper for full methodological details.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).