Earlier this week, the Obama administration released guidance that impacts the way that adjunct professors are paid. The new guidelines indicate that institutions should count hours that adjunct faculty spend preparing in addition to the time that they spend in the classroom. This modest step comes after months of heated debate about the issue of fair compensation for adjunct faculty. A report released last month by the democratic staff of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce captures many of the arguments for greater oversight. The report, which is based on an informal survey, affirmed that many adjunct professors feel both under-compensated and overworked and have concerns about the legality of their inability to access employer sponsored health insurance. The significance of these issues is heightened by the fact that adjuncts make up a growing fraction of the instructional staff at post-secondary institutions.

While it is easy to sympathize with the plight of these highly educated, yet poorly compensated individuals, it’s not clear that federal policy can or should do anything beyond enforcement of existing labor law. Surely there are many occupations in which workers would prefer to be compensated more generously. In fact, you might be hard pressed to find a group of workers who would turn down a raise. From this perspective, it is difficult to justify the government intervening in the labor market for college professors — not to mention that more generous compensation for faculty would lead to higher costs for students with potentially negative impacts on access.

Rather than creating a distortion in the labor market for professors through aggressive regulation, policy makers should take steps to ensure that this market can work efficiently on its own. The composition and employment status of the teaching faculty at an institution should reflect the market demand, rather than the preferences of policy makers. In the current environment, there is a general sense of indifference about this issue among students. We don’t often hear about students evaluating prospective colleges on the basis of their faculty workforce model. As a result, institutions are incentivized to simply minimize labor costs. It is conceivable that as students become more aware of this issue they will demand full-time, more generously compensated instructors, but it is also conceivable that they will prefer the lower cost option once the trade-offs are made more salient.

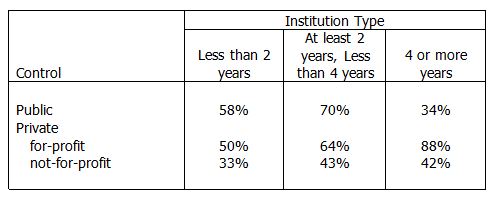

While the coverage of this issue often portrays students as unsuspecting victims of this trend, that doesn’t need to be the case. If students were to have a preference over different labor practices it would not be difficult to select an institution that satisfies their preference. The table below shows the fraction of the instructional faculty that is employed part-time at different types of institutions. It is clear that the reliance on adjunct faculty varies widely across types of institutions. For instance, nearly 90 percent of instructional faculty at for-profit, 4-year institutions are employed part-time while only 34 percent of instructional faculty at 4-year public institutions and 42 percent of faculty at 4-year, not-for-profit private schools are part-time employees. At institutions offering associates degree programs, the fraction of faculty employed part-time ranges from 43 percent at private not-for-profit institutions to 70 percent at public institutions, including community colleges. There is further variation within these categories and yet even further variation in the experiences of individual students. While students may not often exercise a preference over this dimension, the market does continue to offer choice.

Fraction of Instructional Faculty Employed Part-time at Title IV Institutions

Source and note: IPEDS, universe is Title IV participating institutions

There are two reasons to think that students, the consumers of education, would care about the employment status of their instructors. First, it could be the case that instruction quality is systematically different between full-time and part-time faculty. Second, students may care about the well-being of their professors. While it is somewhat contrary to classical economic theory to argue that students would prefer a production process that raises their cost without necessarily improving quality, there is precedent for this type of behavior. One example is the market for fair trade coffee. Many coffee drinkers are willing to pay a premium for fair trade coffee when they could buy a comparable (or even superior) product for less. These consumers derive some value from knowing that the coffee growers are paid more generously than they would be otherwise. It is not inconceivable that some students might prefer institutions that employ better compensated faculty for similar reasons.

It is more likely, however, that preferences over labor practices will be driven by actual differences in quality. Many of the anecdotes gathered in the committee report indicate that adjuncts feel that the necessity of working multiple jobs makes them unable to devote sufficient time to their students. Some mentioned that the compensation is insufficient to allow them to be available to students outside of the classroom. However, there is limited evidence about the effectiveness of different types of faculty. One recent study [i] indicates that adjunct faculty perform just as well as full-time faculty, while others have found evidence to the contrary (a discussion of this work can be found here). A recent Brown Center report provides some additional evidence on this issue, suggesting that instructors with master’s degrees are more effective than instructors with doctoral degrees and full-time instructors are more effective than part-time instructors. The mixed findings suggest, perhaps, that the efficacy of the adjunct model varies with the institutional setting.

The answer to this challenge is not to introduce regulation that dictates the way that post-secondary institutions can utilize labor. Any rigid policies regarding adjunct faculty are likely to leave students worse off because they would limit the ability of institutions to be innovative. The current debate focuses on the tradeoffs between using full-time professors, who usually split their attention between teaching and research, and adjunct professors, who by all accounts are paid meager wages and have little incentive to enhance student learning. Surely, there are alternative models that could generate better outcomes for students. The role of policy in this setting is to raise awareness about these issues so that students and their families can develop their own informed preferences. At a time when student success is at the forefront of every policy discussion, we are all grateful for the hard work and passion of the adjunct faculty serving at our nation’s postsecondary institutions. However, moving toward a regime of federally mandated “fair trade” faculty is questionable, at best.

[i] Marilyn Sherman, David Figlio, Morton Shapiro “Are Tenure Track Professors Better Teachers?” NBER Working Paper 19406, September 2013

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fair Trade Faculty: Should Policy Enforce a Living Wage for Adjuncts?

February 12, 2014