For the past six months, the Center for a New American Security and the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy have convened regular meetings of a Task Force on the Future of U.S. Foreign Policy toward Gaza. The recommendations outlined in this report were informed by the deliberations of that group and reflect the ideas that emerged from the discussions, but the report and the recommendations therein represent the views of the authors alone, not all of the task force members. The authors are deeply grateful for the effort, advice, and dedication of the task force members.

Executive Summary

Situation Overview

A crisis is unfolding in the Gaza Strip. Its nearly 2 million residents live amid a man-made humanitarian disaster, with severe urban crowding, staggering unemployment, and a dire scarcity of basic services, including electricity, water, and sewage treatment. Three rounds of open warfare have devastated Gaza while endangering Israel, and the situation remains on the brink of another conflict. Gaza’s deterioration further fosters instability in neighboring Sinai while creating opportunities for external extremist influence. Moreover, the continued political and physical separation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank hinders Palestinian national development while making a two-state solution even more remote. Given the moral, security, and political costs of this state of affairs, the United States should no longer accept its perpetuation.

A standoff has persisted since Hamas took over the Gaza Strip in 2007, leading to an ugly and predictable pattern of events. Hamas has repeatedly turned to violence to build political support in Gaza and apply pressure on Israel. Israel, with support from Egypt and, in recent years, from the Palestinian Authority (PA), has used a blockade to deter Hamas and deprive it of materiel. This dynamic has led to intermittent bouts of conflict. When the situation escalates, the international community has stepped in, led by Egypt and the U.N. Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process (UNSCO), to negotiate fragile, temporary cease-fires and marginal economic relief for Gaza. After each conflict, however, no long-term resolution has been found for the severe differences between Israel, Hamas, the PA, and Egypt, and thus the pattern has repeated itself with no end in sight.

U.S. policy on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has focused primarily on final status negotiations between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israel. This limited attention has led to reactive and unimaginative American policy toward Gaza. When Hamas first took power, the United States responded by pursuing a policy that attempted to isolate and then dislodge the group from Gaza. When that failed, the United States shifted to a more passive approach, deferring to others. Throughout, policymakers treated the Gaza Strip as a side issue that would resolve itself once peace was achieved. With no peace agreement likely in the near future, a proactive U.S. policy on Gaza, as part of a broader approach to the Israeli-Palestinian challenge, can no longer wait.

A New American Approach

The authors recommend a new U.S. policy toward Gaza. This will not require a fundamental shift in objectives, but it will demand both a major change in the strategies and tools the United States uses to achieve them and greater American engagement.

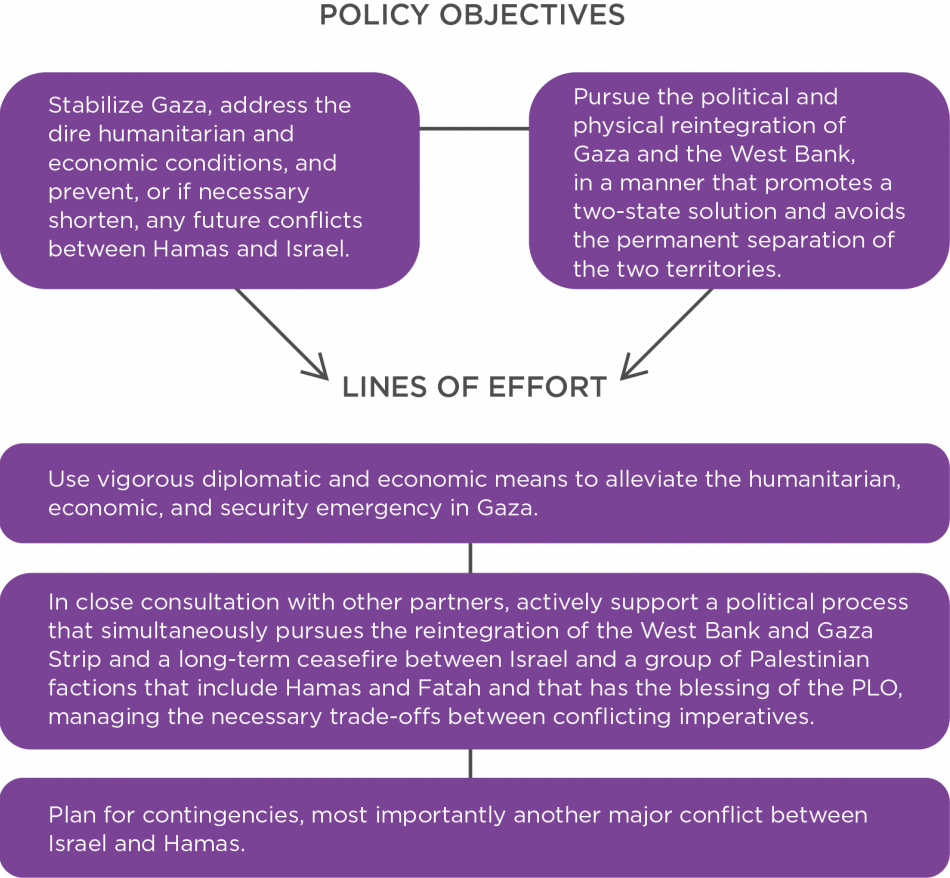

U.S. policy toward Gaza should pursue two central objectives:

- Stabilize Gaza, address the dire humanitarian and economic conditions, and prevent, or if necessary shorten, any future conflicts between Hamas and Israel.

- Pursue the political and physical reintegration of Gaza and the West Bank in a manner that promotes a two-state solution and avoids the permanent separation of the two territories.

These objectives are consistent with past U.S. policy and international efforts that have prioritized either intra-Palestinian reconciliation or a long-term cease-fire between Israel and Hamas. These efforts have failed, in part because they were pursued independently of each other, and they lacked international coordination and proactive U.S. involvement.

Tension exists between these two objectives, and pursuing them simultaneously is difficult. A policy focused on addressing the immediate emergency in Gaza risks reducing pressure on Hamas and legitimizing it, thus weakening the PA in any reintegration negotiation. A policy focused solely on reintegrating Gaza and the West Bank may take years, during which time the humanitarian crisis will likely worsen. Despite this tension, U.S. policy can and should pursue both objectives, recognizing the balance required and managing the necessary tradeoffs between conflicting imperatives. From these two objectives, the authors derive a strategy consisting of three lines of effort, which should be pursued with far greater intensity than in the past:

- Use vigorous diplomatic and economic means to alleviate the humanitarian, economic, and security emergency in Gaza.

- In close consultation with other partners, actively support a political process that simultaneously pursues the reintegration of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and a long-term cease-fire between Israel and a group of Palestinian factions that includes Hamas and Fatah and that has the blessing of the PLO, managing the necessary tradeoffs between conflicting imperatives.

- Plan for contingencies, most importantly another major conflict between Israel and Hamas.

While shifting away from the West Bank-first policy, the United States must avoid a Gaza-only strategy that ignores the peace effort between Israel and the PLO. Such neglect would cement Palestinian division, empower Hamas at the expense of the PA, and scuttle any chance of an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal in the future.

A new U.S. policy toward Gaza will not require a fundamental shift in objectives, but it will demand both a major change in the strategies and tools the United States uses to achieve them and greater American engagement.

Before the United States can credibly promote a resolution of the crisis in Gaza, however, it must walk away from several major recent policy decisions. It must recommit to pursuing a two-state solution and act in a manner that supports that objective. This includes restoring U.S. funds to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), especially for its vital Gaza operations, and finding ways to close the breach with the PA that followed the decisions to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem and subsume the U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem into the U.S. Embassy. Without such a commitment, many critical players – most importantly the PA – will view American efforts with deep suspicion, worrying that the U.S. focus on Gaza is simply an effort to permanently separate the Palestinian polity and foreclose the possibility of a two-state solution. This must not be the U.S. objective, and it must not be seen as such. As long as the Trump administration continues to pursue its current policies, any effort by the United States to take on a greater role in Gaza will be dead on arrival.

Table 1. Alleviating the Humanitarian, Economic, and Security Crisis in Gaza

| Freedom of Movement | Electricity | Water | Social Services | Administrative Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allow more Gaza workers to return to Israel, gradually increasing the number while accounting for security considerations. | Increase the supply of fuel to Gaza Power Plant so it can function at full capacity. | Repair pipes to stop widespread local water loss. | Reinstate UNRWA funding, allowing for Gaza services to be fully restored. | Expand assistance and range of U.S. activities allowed in Gaza. |

| Allow new categories of individuals to regularly and reliably travel from Gaza to Israel, the West Bank, and elsewhere. | Double Egyptian supply to over 50 Megawatts. | Double the water supply from Israel. | Support PA resuming salary payments but rationalizing them down over time. | Once U.S. assistance is restored, double U.S. staffing footprint in Gaza. |

| Ease significantly import and export restrictions. | Double Israeli supply to 200-240 MW. | Accelerate sewage treatment. | Appoint an economic coordinator who reports directly to the special envoy. | |

| Permanently ease fishing restrictions. | Long-term, large-scale desalinization. | Build online resource center to coordinate international donors. | ||

| Reopen and develop industrial zones on Gaza side of the border. |

Immediate Stabilization

Given Gaza’s size and population density, its economy cannot function while closed. Even if its nearly 2 million residents were provided with access to unlimited electricity and water, they could not afford to buy it without jobs. Such jobs could only be provided within the context of a viable economy, and a viable Gazan economy requires a vastly freer flow of people and goods as well as the provision of water and electricity. These issues, in other words, are deeply connected – without progress on all, progress on any one area will be limited.

Several steps should be taken to increase freedom of movement and economic activity. Israel should gradually reissue permits to residents of Gaza to work in Israel, increasing their number from a small initial amount over time, and it should also allow new categories of people to leave Gaza for business and professional training. Other key steps include: reopening and upgrading industrial zones just inside Gaza’s borders with Israel and Egypt; expanding fishing zones off the Gaza coast; and easing dual-use restrictions on imports as well as other restrictions on exports.

The international community should simultaneously work to address the water and electricity emergencies directly. Israel and Egypt should take steps to boost the supply of electricity they make available for sale in Gaza, as both have indicated they are keen to do, while the PA should reduce the cost of fuel in Gaza so its power plant can operate at greater capacity. Renewable sources of energy, such as solar fields inside and just outside of Gaza, can be quickly and cheaply developed. Support from international donors will continue to be necessary to provide for Gaza’s short-term electricity expenses until improving economic conditions allow Gaza’s residents to pay for it themselves.

To increase the supply of potable water, international aid should focus on existing infrastructure and fixing a rampant problem of leaky pipes, and on short- and long-term desalination projects. More water should be piped in from Israel. Continued funding is also necessary to guarantee electricity for Gaza’s main sewage treatment plant. In addition, Israel should ease its dual-use restrictions to allow in the materials needed to complete the construction of new sewage treatment plants.

If the United States is to play a serious and credible role in improving the situation in Gaza, Washington should go beyond these areas, resuming funding to UNRWA so it can restore services in Gaza, restoring and indeed expanding the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) assistance that goes to Gaza, and supporting cash-for-work programs. The United States should also at least double its local-hire Gaza staffing footprint, consider allowing American officials to re-enter Gaza after a 15-year absence, and create a senior position focused on improving the situation on the ground in both the West Bank and Gaza to knit together the various relevant U.S. government entities both in Washington and the region. This person should report directly to the senior U.S. official responsible for overseeing the Israeli-Palestinian issue.

Sustainable Political Arrangements

The authors recommend working toward a sustainable political arrangement on two pillars, pursued as part of a wider initiative: (1) an agreement between the PA and Hamas on the gradual reintegration of the West Bank and Gaza, and (2) a long-term cease-fire between Israel and a group of Palestinian factions that includes Hamas and Fatah and that has the blessing of the PLO.

Numerous efforts to pursue these tracks independently have failed. Integrating them would bring a greater chance of success. For example, a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas would require the easing of the blockade, which is only possible with Israeli consent, a much harder prospect without a PA presence in Gaza. Similarly, reintegration without a serious cease-fire would last only as long as the quiet lasts, as a new major Hamas-Israel conflict would make it impossible for the PA to continue to simultaneously integrate with Hamas while maintaining peace with Israel.

Table 2. Summary of a Sustainable Political Arrangement

| Hamas | PA/PLO | Israel |

|---|---|---|

| Accept the PLO’s continued role as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. | Allow for the establishment of a joint committee for consultation on governance that would include Fatah, Hamas, and other key political parties and draw its legitimacy from the PLO. | Agree to Palestinian reintegration and to working with a Palestinian national unity government, including people acceptable to, if not members of, Hamas. |

| Agree to abide by a long-term cease-fire in Gaza. | Agree to a process to reintegrate the public-sector workforce in Gaza. | Agree to meaningful gestures to the PA/PLO in the West Bank such as the reclassification of a portion of Area C into Area B. |

| Suspend military operations in the West Bank. | Take a much more proactive posture in supporting infrastructure and long-term economic development in Gaza. Play a central role as part of the delegation that negotiates a long-term Gaza cease-fire. | Agree to significant long-term relaxation of restrictions on the movement of people and goods into and out of Gaza, most importantly by offering a meaningful number of work permits for the residents of Gaza. |

| Freeze any expansion of its military capabilities, destroy its attack tunnels, commit to not launch rockets, and agree to a gradual process for dismantling its offensive capabilities. | Retake control of the ministries responsible for key services inside Gaza. | Agree not to hold the PA/PLO responsible for any and all rocket fire or other attacks coming out of Gaza – instead continuing to hold Hamas directly responsible. |

| Relinquish its control of key civilian governing ministries inside Gaza. | Gradually insert PA security forces to Gaza, first at the border crossings and over time inside the Strip. | |

| Agree to a process to reintegrate the public-sector workforce in Gaza. | ||

| Work toward a long-term vetting process to integrate its security forces in Gaza with PA security forces, which would gradually re-enter Gaza starting with the border crossings. |

Should such an arrangement succeed, Hamas would see an end to the Gaza Strip’s economic strangulation and could relinquish unwanted governing responsibilities in Gaza while being included in Palestinian political decision-making. Israel would receive sustained long-term quiet. And the PA would receive both the national unity ordinary Palestinians desire in overwhelming numbers and actions from Israel and/or international players that strengthen its position in the West Bank and signal progress toward a two-state solution.

This proposal would require concessions by all parties. Hamas would have to agree to a long-term suspension of hostilities, allow the PA back into the Gaza Strip, and enter into a process that would include significantly reducing its military capabilities. Israel would have to significantly ease restrictions on the movement of goods and people in and out of Gaza, despite its security concerns, and hold Hamas, not the PA, responsible for infringements of the cease-fire. Israel would also have to agree to one meaningful step inside the West Bank to signal to the PA its continued commitment to a two-state solution. The PA would have to retake control over the ministries faced with the daunting task of servicing Gaza’s battered population while accepting Hamas’ inclusion in Palestinian-wide decision-making. Both Israel and the PA would also have to accept that Hamas would retain some of its military capabilities for the time being.

While this agreement may be unlikely today, the authors believe that when a moment of opportunity presents itself, it is the political formula most likely to succeed.

A Greater American Role in Orchestrating a Solution

The strategy described requires effective coordination between the many interested international actors. This can only be achieved if the United States uses its influence to help coordinate the effort in close partnership with Egypt and UNSCO. The United States should not attempt to take over the process, pushing out other key players, as its limited influence with the Palestinian actors means it cannot single-handedly solve this problem. The United States does not engage with Hamas and the authors do not recommend opening any such direct channel. Additionally, the United States’ relations with the PA have soured dramatically in recent months. The United States does, however, have the greatest influence of any actor with Israel, the various Gulf states, the European Union (EU), and many European countries, and so has a special role to play in this effort.

The United States, UNSCO, and Egypt should work quietly in concert, engaging with Israel, the PA, Hamas, and the international community on a common vision for the economic development of Gaza, while simultaneously the United States and UNSCO can forge ahead with an economic development agenda for the West Bank. Once goals and methods are aligned, the parties should form an international coalition in which outside players can take coordinated leadership roles in various subsectors or projects. As part of this effort, the United States should back an international mechanism being set up by UNSCO to provide more direct, emergency relief in Gaza.

A similar U.S.-Egyptian-UNSCO partnership should guide the pursuit of a long-term political arrangement. Egypt and UNSCO can bring their leverage with Hamas and the PA and experience in previous intra-Palestinian reconciliation and Israel-Hamas cease-fire negotiations, while the United States can offer its unique influence with other actors. Egypt, UNSCO, and the United States, consulting with the parties, should agree on a common political plan and rally the other external actors.

As part of this effort, the United States should both press the Gulf states and Arab League to publicly pressure Hamas to accept the authority of the PA and encourage the constructive role Qatar has played in providing aid to Gaza, but make sure the Qatari message to Hamas is that the Egyptian-U.N.-U.S. plan is the only political option. Europe should present the PA with incentives to enter into a political arrangement and provide pressure when necessary. Getting agreement from Israel, Hamas, and the PA/PLO will still be extraordinarily difficult, but a campaign coordinated between all the external actors has the greatest likelihood of success.

Table 3. Coordination of Key Roles by External Actors

United States

- Play the role of international coordinator, pressing all of the external actors to line up behind an Egypt-U.N.-U.S. approach.

- Use its special relationship with Israel to encourage it to end the blockade, take steps in the West Bank that strengthen the PA, and show it is serious about a two-state solution.

- Re-establish some influence and leverage with the PA by reversing some of the recent policy shifts.

Egypt

- Continue to play the role of mediator between the PA and Hamas in negotiating a reintegration arrangement.

- Work with Israel on loosening the blockade, using its strong defense relationship and geographic location.

- Provide additional electricity to Gaza in the near term.

- Play a role in monitoring and execution of any agreement.

U.N./UNSCO

- Take on a greater role in implementing projects inside Gaza.

- Act as real-time mediator between Israel and Hamas.

- Given the U.N.’s central role in the PA’s internationalization strategy, encourage the PA to be more flexible in taking on a greater role in Gaza.

Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates

- Incentivize Israeli and PA cooperation in an agreement on Gaza by offering openings to Israel and financial aid to the PA and projects in Gaza.

- Make a declaratory statement supported by the Arab League that affirms the importance of “one authority, one gun” in Gaza.

Qatar

- Continue to act as a significant donor for financial projects inside Gaza. Coordinate carefully with UNSCO and the United States to make sure these projects reinforce the Egypt-UNSCO-U.S. plan.

- Ensure that any political mediation does not conflict with the Egyptian role.

Europe

- Incentivize PA cooperation, such as by offering greater recognition and diplomatic support, tied to progress on Gaza.

- Reprogram funding and assistance if the PA is not cooperative in pursuing a constructive solution for Gaza or tries to financially strangle Gaza.

- Provide economic and political incentives and disincentives for Israel as part of a Gaza package.

- Non-EU countries, especially Switzerland and Norway, can play a constructive role in encouraging and echoing the political plan with Hamas and coordinating aid from Europe into Gaza.

- Switzerland and Norway can assist in the implementation and monitoring of any agreement.

Jordan

- Use its relationship with the PA and Israel to press both sides to agree to the Egypt-U.N.-U.S. plan.

Turkey

- Provide funding for projects inside of Gaza but only through the agreed funding mechanism. Coordinate carefully with UNSCO and the United States to make sure these projects reinforce the Egypt-UNSCO-U.S. plan.

- Avoid (and be dissuaded by the United States from) playing a role in the political mediation process other than reinforcing support for the Egypt-UNSCO-U.S. plan.

Contingency Planning

American policy should prepare for significant changes in the political landscape that may create severe challenges but also new opportunities. The most important scenario would be a major new military conflict between Israel and Hamas. The United States should also be ready for a change in Israeli or Palestinian leadership that could create new opportunities for a breakthrough.

The United States should do everything possible to prevent fighting. However, should conflict break out, it could create a moment in which all sides feel immense pressure to be more flexible. In such a scenario, the United States and the international community should avoid the temptation to again take the simplest route, with Egypt negotiating a “quiet-for-quiet” deal that ends immediate hostilities but preserves the status quo. Instead, the parties should pursue a more detailed and comprehensive agreement such as the one outlined below.

Such an agreement cannot possibly be developed from scratch in the middle of a fast-paced war. If the United States were to pursue the political arrangements recommended in this report now, however, the groundwork could be laid for the parties to accept this outcome in a moment of crisis. Thus, even if the PA, Israel, and Hamas are not yet ready to accept such a formula today, pursuing it now could facilitate its success in the future.

Conclusion

The situation in Gaza holds extraordinary challenges, and the authors recognize that the critical parties may reject these proposals many times before they have a chance to succeed. The framework laid out in this report, however, presents the best chance to escape the present situation. In proposing an effort focused both on the political reintegration of the Palestinian polity and the stabilization of Gaza, in the short and long terms, the authors aim to move past the failed policies of the past dozen years. The United States can contribute greatly to this effort. It should take on a far more active role, working closely with other external actors, Israel, and the Palestinians to end the perpetual disaster in Gaza.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).