President Obama is scheduled to deliver a farewell address on Tuesday, Jan. 10 in Chicago, continuing a longstanding tradition that began with George Washington’s farewell in 1796. Historians largely agree that Washington’s written farewell, along with Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1961 farewell address are the most significant in American history. In this piece, Brookings Senior Fellow Emeritus Stephen Hess shares for the first time his recollections of being on Eisenhower’s speech writing staff at the time of his farewell address, made famous for its warnings against the “military industrial complex.”

Addresses—plural—yes, there were two in 1961 although hardly anyone, even those who were around then, can recall the second one.

President Eisenhower’s chief speechwriter was Malcolm Moos, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins, a man of great charm and ambition, who also happened to be the city chairman of the Republican Party in Baltimore. He brought with him from his native Minnesota a moderate political caste that was not always popular in his party. (He would later become the President of the University of Minnesota.) I like to think that I had been his favorite student, helping him research a history of the Republican Party as well as biking door-to-door when he needed political support.

Almost exactly when Mac joined the White House staff in early September, 1958, the United States Army made me a civilian again. I had been drafted in 1956, sent to Germany (to be replaced in the 3rd Armored Division by Elvis Presley, at least his unit for my unit) and was now a former Private First Class.

Mac brought me to the White House to help on the president’s political speeches during the midterm election. (I was paid by the Republican National Committee until January when I was switched to the White House staff.)

My addition expanded the White House speech writing staff to a team of three. In addition to Mac, I joined Naval Officer Ralph Williams of Pecos, TX in the White House. Ralph was brought to the White House as Assistant Naval Aide to the President. But for years before that, Williams was the recipient of the top prize in the Naval Institute’s annual essay writing contest. Year after year, Ralph worked as a supply officer by day and produced winning essays at night, so when he dropped by to ask Mac if he could be of help, Mac, having never been in the military, was delighted to add an at-hand expert on national security to his team.

My specialty was the political stuff such as the President calling the Republican Party “a hibernating elephant” after badly losing the midterm election (a phrase that became the subject of a Herblock cartoon).

After a Moos-Williams-Hess session to discuss an upcoming speech we each drafted our ideas independently; then Mac, who called himself the “carpenter,” would piece them together to present to the President.

Among Mac’s other duties was being our chief diplomat, protecting speech drafts from the Important People (and sometimes other staffers) who knew just what Eisenhower should be saying. But most important, unlike the case of Mac’s predecessor, law professor Arthur Larson, the President was very comfortable working with Mac.

The three of us were a happy team. Busy, but not overworked; there were lots of “remarks” as in “Remarks at a Dinner Given by the Indiana State Society,” but scripted “addresses” probably averaged only two a month. (Mac and I even found time to complete a little book, Hats in the Ring, published by Random House in 1960.)

The President liked to start with a full text version of a speech and would become more and more involved, draft after draft, until it took on his character. A major speech might go through ten drafts. A draft only changed its number after it had been edited by the President. Because of Ike’s famously awkward responses at press conferences, it always surprised my friends when I told them that he was a superb editor, and had once even been a speechwriter (for Douglas MacArthur). Given the President’s medical history—he had had a mild stroke in 1957—I tried to shorten sentences when I could and he always returned to his own style. He was not especially interested in gimmicks or rhetorical flourish although there were exceptions as when he addressed a national speech to a young woman from Colorado who wrote him a letter asking why she should be a Republican. Primarily I think of him as an informational speaker. His objective was to say something clearly, as precisely and briefly as possible.

…

On May 20, 1959, Mac filed a “memo for record:”

The President mentioned in an aside this morning, when I brought up the topic of selective major addresses for the remainder of his term, that he had one speech he would like very much to make.

He hoped, he said, that the Congress might invite him to address them before he left office, at which time he would like to make a 10 minute farewell address to the Congress and the American people.

I think this is a brilliant idea if it can be carried off with a minimum of fanfare and emotionalism, and we should be dropping ideas into a bin, to get ready for this.

…

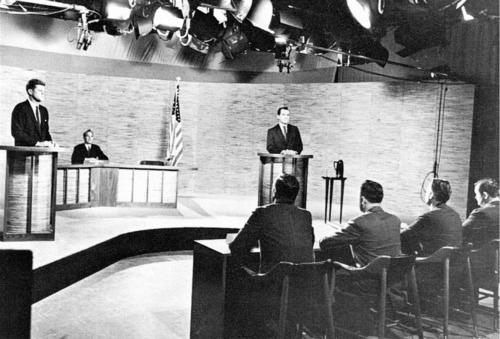

On January 17, 1961, Dwight Eisenhower delivered his now-famous “Farewell Radio and Television Address to the American People:”1“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

The primary writers were Mac and Ralph, with massive additions and corrections from brother Milton Eisenhower, the President of Johns Hopkins. I did not work on the speech except for some early kibitzing.

Eisenhower’s White House staff were expected to live by the “passion for anonymity” rule. For speechwriters this meant that all words were the President’s. Period. A leak to the press or a casual aside at a Georgetown cocktail party on who wrote what would be a hanging offence. There was never the credit-claiming made famous by some subsequent presidents’ speechwriters. Historians tend to simply attribute Ike’s words to the chief speechwriter at the time. Thus the origin of “military-industrial complex” has remained vague. The latest book on the speech, Three Days in January, by Bret Baier, ignores the subject.

Eisenhower had a long history of concern over the growth and cost of the military, especially the air force, and the lobby industry in Washington that promoted expansion.

The speechwriter’s task was simple and crucial: how to join military and industrial to reflect Ike’s concern. One additional word was necessary.

This was Ralph Williams’ solution:

“I think the ‘complex’ part of it came—you know, you get to the end of a sentence and you don’t know how to end it up and this word comes to you and you write it in and that’s the way it fits and that’s the way it came out.”

Ralph’s three words were the most quoted phrase of the Eisenhower presidency. “The military-industrial complex” ranks high among all presidential references.

After his White House service, Ralph was assigned to the Naval Supply Center at Pearl Harbor as comptroller. He retired in 1965 with the rank of Captain. He then entered the civil service, working on mineral resources at the Department of the Interior, ultimately retiring from public service in 1982.

…

Though the White House shelved its initial idea of the farewell address as a congressional event, there was another opportunity for a second leave-taking. It was billed as an “Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union.” Such messages are the traditional way that presidents attempt to set their blueprint for the coming year, but Ike had other plans as he opened his 1961 message:

“Once again it is my Constitutional duty to assess the state of the Union.

“On each such previous occasion during the past eight years I have outlined a forward course designed to achieve our mutual objective—a better America in a world of peace.”

But he then explained:

“My purpose is to review briefly the record of these past eight years in the hope that, out of the sum of these experiences, lessons will emerge that are useful to our Nation.”2

In contrast to the near-philosophical reflections of his January 17 farewell, his second farewell was meant to be a compilation of achievements.

I was given the assignment to draft the President’s assessment of his eight years.

I had about three weeks. The first draft was delivered on New Year’s Eve, December 31. Don’t worry about length, I was instructed. The President is not going to give it in person. It will be read into the record by the House clerk. Long is good.

What should have been a herculean task was not. Six months earlier, I had been directed by the White House chief of staff to compile a narrative of the Eisenhower record for Charles Percy, the chairman of the Republican Party’s platform committee. Eisenhower had no role in this process. The presidential nominee would be Nixon. But Percy was a Chicago industrialist of limited political experience and the White House staff worried that his committee might not be sufficiently appreciative of our boss’ accomplishments.

The platform data needed only to be updated in places. The President did “light editing” on three drafts. Example. Hess: “Thus it is obvious that important adjustments must still come” becomes Ike: “Obviously important adjustments must still come.” Oddly, on the back of page 25 of the January 10 draft Ike doodled a two-inch head in profile, perhaps slightly resembling a self-portrait.

The final message to Congress was 6,500 words, 18 pages of the Public Papers. Seventy-one percent came from the material I had prepared for the platform committee. The organization was straight platform-style: Foreign Policy, National Defense, The Economy, Government Finance and Administration, Agriculture, through Veterans. Others must judge the substance.

Still, deep inside there was something that had not been there before in the Eisenhower history.

On civil rights, Eisenhower had acted with riveting strength in confronting Arkansas Governor Faubus during the Little Rock crisis. Yet on May 17, 1954, when U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that ruled state-sanctioned segregation of public schools unconstitutional, the President’s response was “The Supreme Court has spoken and I am sworn to uphold the constitutional processes in this country; and I will.” Perhaps Eisenhower’s initial restraint accurately calibrated the national threshold on civil rights. Perhaps it was the time to try to rally the nation behind this controversial ruling. His position on civil rights would be that he would do what was a president’s right to do.

This was first reflected in the January 12 message:

“Segregation has been abolished in the Armed Forces, in Veterans’ Hospitals, in all Federal employment, and throughout the District of Columbia—administratively accomplished progress in the field that is unmatched in America’s recent history.”

But he then concludes with these final words as President on civil rights:

“This pioneering work in civil rights must go on. Not only because discrimination is morally wrong, but also because its impact is more than national—it is world-wide.”

There is a moment of joy for a presidential speechwriter when he has something to do with a statement of great importance –in truth, speechwriters will admit this is not often. “Discrimination is morally wrong” was to be my moment.

On January 12, the House clerk read these words to a near-empty chamber. The words were Dwight Eisenhower’s.

-

Footnotes

- Public Papers of the Presidents, 1960-61, pp. 1035-1040

- January 12, 1961, Public Papers of the President, 1960-61, pp. 913-930).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).