Technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence are influencing jobs and workflows across every major industry. However, businesses that want to deploy them are constrained by their capacity to keep employee skills up to date and recruit talent familiar with both the new technology and their industry.

Employers will inevitably need to rethink their talent recruitment and staff development strategies. A way to do this is through apprenticeship programs, which enable employers to play a more active role in shaping the talent they need while also building a culture of ongoing learning and innovation.

Apprenticeships provide long-term paid work-based learning opportunities and structured educational curricula that ensure the learner gains education and hands-on experience in an occupation, similar to how we train medical doctors with a mix of classes and residency experience. Registered apprenticeships are those that are formally approved by either the Department of Labor’s Office of Apprenticeship or a state’s apprenticeship agency. Registration ensures the apprenticeship meets certain criteria to protect apprentices (such as a wage progression) and to maintain quality. Some youth and adult apprenticeship pilots offer high-quality structured education and work experience but are not registered. Short-term work-based learning programs such as internships or staff development programs are not apprenticeships.

An apprenticeship system, rather than a one-off program, offers employers the ability to host apprentices while not having to bear the full costs of starting and maintaining the program themselves. Historically, in the U.S. building trades, labor unions have provided most of the funding, coordinating, and support functions. Other industries often rely on community colleges, workforce development boards, industry associations, private apprentice staffing firms, or community-based organizations.

Given the immense costs of higher education in the U.S. and underproduction of science and technology graduates, relying on college degrees alone for tech-savvy talent not only excludes most Americans, but it is also not enough to prepare organizations for the future of work. Low diversity among science and technology college graduates also stunts the ability of employers to boost innovation and produce stronger financial results. While Black and Latino or Hispanic people make up 30% of adults, they make up only 7% to 8% of people working in computing and mathematical occupations. Employers’ overreliance on college degrees as a proxy for skill in hiring reproduces this racial and economic exclusion, while employers pay a premium to compete in an artificially small labor pool because they cannot easily identify quality talent among candidates without a degree. This is doubly inefficient because diverse teams offer businesses the capacity to reach new markets for products and services.

Modern apprenticeships offer a talent development approach that onboards more diverse talent as well as internal infrastructure to create a learning culture. However, employer buy-in and awareness are major barriers to expanding and modernizing apprenticeships outside trades such as construction or electricians. These barriers are based, in part, on misconceptions or outdated understandings about what apprenticeships are.

This piece presents questions that employers who are new to apprenticeships frequently ask, and draws on available evidence to answer them. The goal is to build a more grounded understanding of the business case for apprenticeships by sharing resources and evidence.

What is the difference between an internship and an apprenticeship?

An intern at a winery may clean up after wine tastings, but an apprentice in viticulture spends years working under the wings of a master winemaker. Internships are short-term, while apprenticeships often last for several years. During the training period, apprentices follow a structured training plan that allows them to master occupational skills in the context of an employer’s organization and spend several hours a week learning general and theoretical content in the classroom.

Internships are usually unstructured and emphasize entry-level work, while apprentices work closely with a mentor to improve their skills and, in registered apprenticeships, they earn a higher wage as they advance. Interns rarely experience close work with a committed mentor and may or may not be compensated for their work. Finally, apprenticeships earn an industry-recognized credential upon completion of the program and often convert into a regular employee; internships rarely lead to any formal certifications and are less geared toward conversion.

How long is a typical apprenticeship?

Program length varies by occupation, employer sponsor, and apprenticeship model. While many apprenticeships require apprentices to complete a minimum of 2,000 work hours, others (such as electricians) require upwards of 12,000 hours. Registered apprenticeships can be based on competencies rather than recorded hours (or a hybrid of hours and competencies). Competency frameworks allow apprentices to complete their programs on a variable basis as they demonstrate mastery. Most apprentices complete their programs within one to six years.

What is the return on investment for apprenticeships?

Evidence suggests that returns on investment for employers vary greatly, but are generally positive. Several variables shape the costs and benefits of apprenticeships, such as industry and occupation, market for apprentices, and institutional and regulatory frameworks. Apprenticeships are not a solution for all employees or roles within an organization, but many firms find them valuable. Employers should view apprenticeships as a capital investment to account for both short- and long-run costs and benefits, as well as indirect costs and benefits.

The most significant direct cost is apprentice wages. Other costs include developing curricula or materials for training, the mentor’s time, and equipment suitable for early-stage training. Although poaching is a common concern among employers, studies suggest that it is not a major concern or cost among employers in practice as long as they earn back their training costs during the training period, retain enough apprentices, or save sufficiently on hiring costs overall. Grant-based assistance or public subsidies can help with startup costs, especially in registering the program or joining an existing program.

The direct benefits to employers are savings on overtime expenses, increased revenue and productivity, and lower recruitment costs.

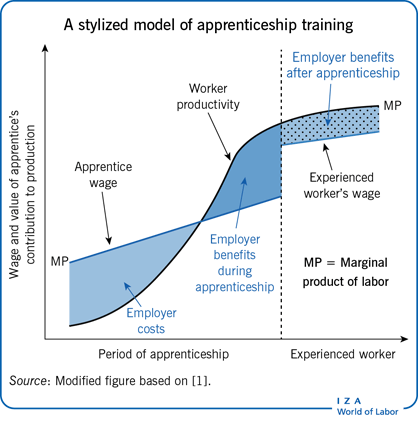

The duration of the training period affects employers’ return on investment. An employer can expect to see a return on investment because apprentices engage in productive activity along with training. Often, as shown in the below diagram adapted from Lerman, a longer training period frame increases return on investment for the employer.

Reducing the training period to minimize costs limits an employer’s ability to recoup those costs because the greatest costs and lowest benefits tend to be in the first year. The optimal duration balances a reasonable likelihood of return for the employer within the training period while protecting the apprentice from being stuck with a lower wage well past the time when they are performing at the level of an experienced worker.

How can employers optimize return on investment?

Employers should consider these tradeoffs that shape return on investment for apprenticeships:

- The mix of activities the apprentice does and the duration of the training period. The share of time spent in the on-the-job component doing firm-specific and productive activities increases benefits to employers in the short run. However, firms can also benefit from investing in more general skill training if that learning leads to greater productivity increases over time.

- The pay structure and credentialing. Apprentice wages are the largest direct cost, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that minimizing wages is the optimal choice. An employer can go beyond the minimum if the goal is to attract more competitive apprenticeship candidates. Apprenticeships with lower pay scales can remain attractive for quality talent (especially young adults) when the apprenticeship results in a nationally recognized credential or degree that allows the apprentice to demonstrate their qualifications in the labor market. Regulations for registered apprenticeships are flexible but do require wage progression and credentialing.

- The criteria for selecting apprentices and depth of apprentice training and mentorship. Employers can recruit apprentices at a higher level of skill and experience to reduce the costs of longer-term mentoring during the apprenticeship period. But doing so could reduce the return on investment, because those candidates have higher-wage alternatives on the labor market. Such a strategy also works against inclusion and equity goals for investing in underrepresented talent and associated revenue gains. Furthermore, it could restrict the size of the talent pool in ways that require costs to establish a stable source of apprenticeship candidates.

Apprenticeships are intended to be a learn-by-doing equivalent to college, and therefore should be designed as a quality higher education experience—the type of program that the employer would want to recruit midlevel professionals from. In the long-run, an apprenticeship program that balances the needs of the employer, the apprentice, and existing employees can more reliably benefit the firm.

What are the indirect costs and benefits of apprenticeships?

Employers should consider indirect factors when creating an apprenticeship. Indirect costs include overhead, human resources capacity, “red tape” for registering an apprenticeship, fulfilling compliance responsibilities, and certifying trainers. Intermediaries offer assistance to employers to help reduce these costs. Registration processes that incorporate user-centered design for easy navigation and electronic or automated reporting can reduce those costs for employers and also provide transparency for apprentices to understand their progress.

Employers also report indirect benefits: increased innovation, improved morale from mentoring junior staff, lower turnover, less need for supervision, lower error rates, an option to hire talent with company-specific knowledge, opportunities to develop future managers, and the ability to increase the size of the labor pool.

How can small and medium-sized businesses enjoy the benefits of apprenticeships?

Smaller businesses often struggle to launch an apprenticeship program because of limited overhead and human resources capacity. Apprenticeship programs are least expensive when they involve working with partners, rather than bearing all of the costs internally within the firm. Small and medium-sized companies have several options for cost sharing.

First, small businesses can participate in an existing industry partnership or form new partnerships with the goal of sharing costs for program design, equipment, outreach, etc. Below are some examples of industry-led consortia and partnerships involving small businesses.

- The North Carolina Triangle Apprenticeship Program (NCTAP) aims to develop technology and engineering talent in the Research Triangle area through a four-year program starting in the 11th grade.

- CareerWise Colorado works with educators and employers in seven industries to create and operate modern youth apprenticeships. The model is expanding to New York City, Washington, D.C., and Elkhart County, Ind.

- The Chicago Apprenticeship Network, founded by Aon, Accenture, and Zurich North America, has now expanded to include upward of 40 companies across various industries, as well as several education and nonprofit partners.

The National Skills Coalition has a report with additional examples of industry-driven partnerships for work-based learning, and an Urban Institute report has examples of apprenticeship consortia.

A second option is using intermediaries that work with employers to take on activities such as training employees, providing assistance with the registration process, designing the program, or recruiting suitable candidates. The intermediaries available for this support vary by region and industry.

Finally, to qualify as a registered apprenticeship, the program must involve some amount of classroom training (related instruction). Partnering with publicly subsidized education related to the occupation (especially early in the apprenticeship) can also reduce employer training costs.

How can apprenticeships improve diversity and inclusion in an organization?

Registered apprenticeships are uniquely positioned to build the skills of low-income workers and move them into high-quality jobs. Unlike a traditional college education, apprenticeships emphasize learning by doing and give workers the opportunity to earn a wage while learning. With an enabling policy framework, apprenticeships can offer a paid path to a degree, rather than a separate path away from a degree, counteracting the historical legacy of racialized tracking in the U.S. These features make registered apprenticeships appealing for individuals with family obligations, those who cannot take on large debts, or those who cannot give up working to go to college. Given the extent of occupational segregation in the U.S. labor market, these programs expand opportunities for low-income, female, Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American workers to access quality jobs.

Currently, however, registered apprenticeships in the trades have very limited gender diversity, mirroring the demographic composition of their respective industries. In 2019, 88% of new apprentices entering into federally registered programs were male. Among higher-paid science and technology apprentices between 2000 and 2016, 70% were white—highlighting the need for racial inclusion in high-wage occupations such as software engineering. Companies should take active steps to expand access to registered apprenticeships for women, people of color, people with disabilities, returning citizens, veterans, and members of other underrepresented groups, because diverse leadership and teams improve bottom-line results and lead to other benefits, such as greater innovation.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are not automatic outcomes of apprenticeships—they must be intentionally designed to be inclusive. Employers should first establish program components and metrics for increasing diversity and inclusion within their hiring and management process, setting goals and regularly evaluating progress. To reach these goals, program sponsors could help apprentices learn employability skills early in their careers. They can mitigate unconscious bias in hiring practices, recruit from more diverse sources of talent, establish peer support networks, train team leaders on managing diverse teams, and encourage current employees to pursue apprenticeship opportunities.

Employers should think carefully about their selection criteria for apprentices. Entry-level criteria are the easiest to source talent for, while requiring a higher qualification level will necessitate more focus on recruitment and retention and risks undermining inclusion and diversity goals. In general, apprentice selection criteria place less emphasis on existing technical skills than a regular hire, but test for traits such as adaptability, willingness to learn, the ability to demonstrate how they approach solving a problem, and teamwork. Rethinking the hiring processes to be more inclusive is a critical step.

Direct entry is also an option, including partnering with a pre-apprenticeship program that reflects the employer’s preferences. Pre-apprenticeships can support employers in their efforts to reach a wider pool of apprenticeship candidates. Community-based organizations that operate pre-apprenticeships often have a rich understanding of the needs of the people in their community, so they are well positioned to provide culturally appropriate preparation, accommodations, referrals, or safe spaces to raise and address challenges. Apprenticeship.gov has a pre-apprenticeship program search feature.

Finally, to ensure lasting success, employers should ensure that wages and management practices are equitable, apprentices feel welcome and supported, and those who are hired as regular employees after the apprenticeship have equitable pay and advancement opportunities compared to employees recruited through traditional methods.

What will the National Apprenticeship Act of 2021 do for employers?

On February 5, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the National Apprenticeship Act of 2021, and it will soon proceed to the Senate. The bill would more than double grant funding for intermediaries while increasing state and federal capacity to update, expand, and scale registered apprenticeships. This would help make the registration process more accessible and relevant to employers in a wider range of industries and occupations. The bill also has provisions for raising awareness and increasing access for underrepresented groups, which can help employers find diverse sources of talent. This fact sheet has more details.

What are some other resources on apprenticeships?

The Department of Labor’s website has many resources for employers interested in learning more about apprenticeships and identifying partners. The Chicago Apprenticeship Network also has a playbook that outlines the process of starting an apprenticeship program and factors to consider.

The Urban Institute collaborated with the Department of Labor to create a resource that outlines competency-based frameworks for occupations across seven industries: advanced manufacturing, energy, finance, health care, hospitality, information technology, and transportation. These frameworks may be helpful for employers to design a structured learning program and negotiate with education partners about which aspects of learning will be taught by whom. With funding from the Department of Labor, the Urban Institute offers free technical assistance in starting apprenticeships, as do other contractors.

Success also depends on designing a process for regularly assessing apprentices’ performance, measuring costs and benefits, and gathering ongoing feedback from apprentices. The Chicago Apprenticeship Network’s playbook recommends several metrics. Report cards, such as this Connecticut progress report, are common and require the apprentice to enter the number of hours worked on a specific task. Under this system, the mentor checks this report monthly and grades apprentices on their progress.

Apprenticeships can spark a cultural shift among employers

As with any organizational change, employers seeking to adapt their talent development strategy for the current economy and become more inclusive in their hiring and management practices should approach apprenticeships as a cultural shift across several dimensions:

- From charity to talent investment: Rather than a corporate social responsibility endeavor, diversity and inclusion initiatives and apprenticeship programs are talent investment efforts with benefits for businesses, apprentices, and incumbent workers.

- From consuming to co-producing talent: By playing a larger role in talent cultivation, employers can change how they engage with higher education, from a transactional approach to an ongoing collaboration that builds a pipeline of talent with a combination of company-specific and more general skills that can have many long-term benefits for the firm.

- From risk to asset: By investing in young adults and workers that a traditional hiring and recruitment process might otherwise overlook, employers can cultivate homegrown talent that is molded by the employer’s organizational values, create a culture of learning and mentorship, and develop future managers.

We need more research and measurement of the nation’s modern apprenticeship programs. There is also room for companies in different sectors to continue to innovate in order to identify the optimal balance of training, learning, and productive work in their organization and align it with the organization’s core goals. If Congress passes legislation to expand apprenticeships, there will be more opportunities to learn from and scale what works to make them an integral part of our education and training system.

Resources for more information

U.S. Department of Labor’s apprenticeship website

A Quick-Start Toolkit for Building Registered Apprenticeship Programs

The Urban Institute’s competency-based frameworks for apprenticeships

Chicago Apprenticeship Network playbook

New America’s Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship resource guide

Jobs for the Future’s Center for Apprenticeship & Work-Based Learning

Congressional Research Service’s FAQ on Registered Apprenticeship

Apprenti’s FAQ for employers (targeting the technology sector)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Robert Lerman, Alan Berube, Dr. Katherine Caves, Kirsten Lundgren, Annie Tahtinen, Kristin Wolff, Tracy Hadden Loh, and Dr. Richard Reeves for helpful feedback and suggestions.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful to Dr. Robert Lerman, Alan Berube, Dr. Katherine Caves, Kirsten Lundgren, Annie Tahtinen, Kristin Wolff, Tracy Hadden Loh, and Dr. Richard Reeves for helpful feedback and suggestions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).