Below is the sixth chapter from “A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice,” a report by the Brookings-AEI Working Group on Criminal Justice Reform. You can access other chapters from the report here.

People involved in the correctional system in the U.S. tend to be undereducated and underemployed compared to the general population. Roughly two-fifths of the people entering prison do not have a high school degree or General Educational Development (GED) credential,1 a rate which is three times higher than for adults in the U.S.2 The disparity for postsecondary education is even greater, where the rate at which adults have an associate’s degree or more is four times higher than what has been observed for prisoners.

Due to the stigmatizing mark of a criminal record along with the association between education levels and employment,3 relatively high rates of unemployment have been observed for correctional populations. A number of studies have shown that the pre-prison employment rate (in the year before coming to prison) for people in prison is no higher than 35 percent.4 Post-release employment rates have been found to increase shortly after individuals were released from prison but later decline,5 eventually returning to pre-prison employment levels within a few years.6

Level Setting

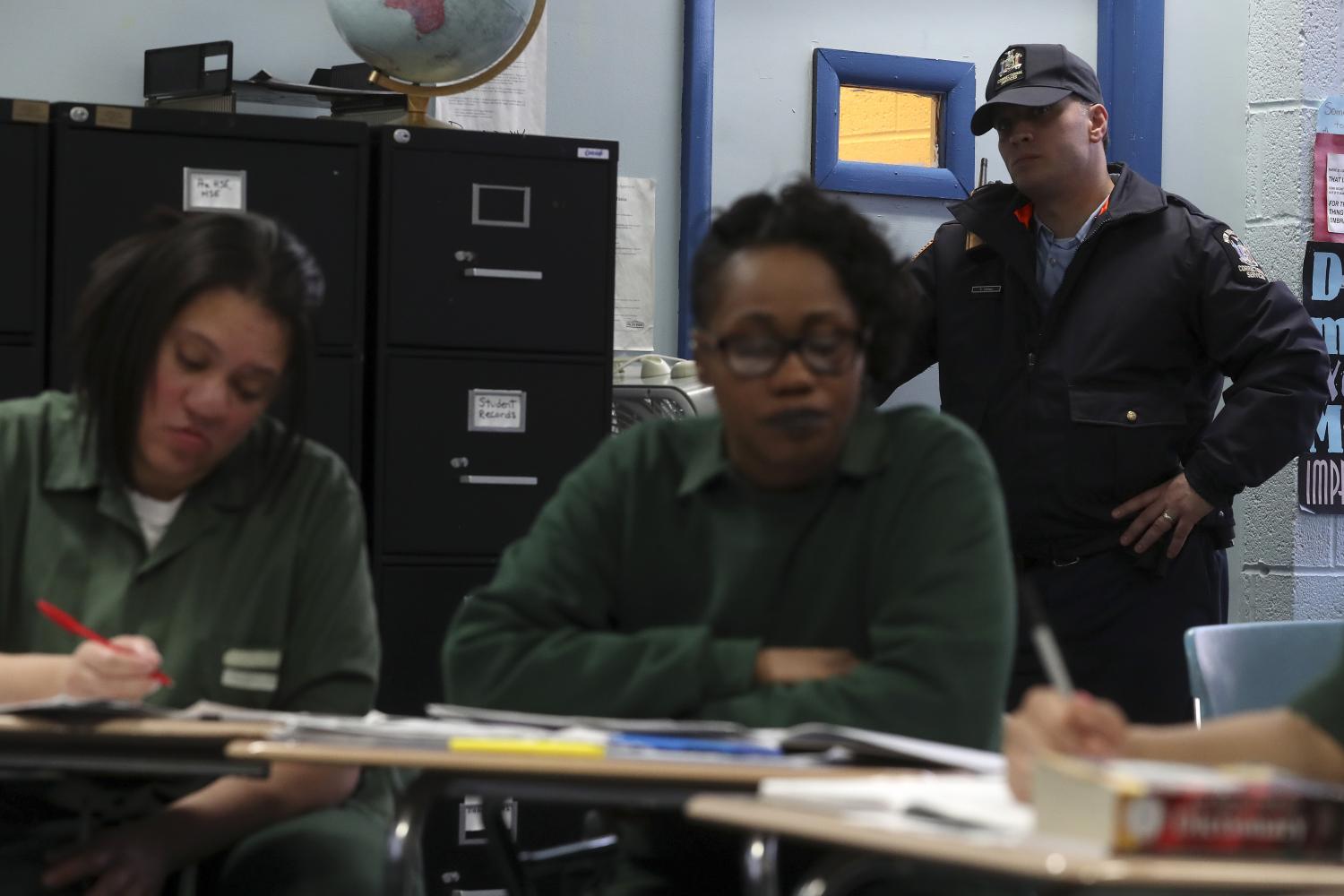

Education Programming

The emphasis on providing education programming for correctional populations is due not only to the lower observed rates of educational attainment but also to the well-documented relationship between low educational achievement and increased antisocial behaviors.7 Education and employment have each been identified as moderate risk factors for recidivism, which is the metric often used to determine the effectiveness of correctional programming. Risk factors for recidivism have been categorized as major (history of antisocial behavior, antisocial personality pattern, antisocial cognition, and antisocial associates), moderate (education/employment, family/marital, leisure/recreation, and substance abuse), and minor (low IQ and social class).8

Meta-analyses of prison education research have shown that it reduces recidivism, although the effect sizes have ranged from modest9 to relatively large.10 Prison education has been found to be more effective in lowering recidivism when participants complete the course or program,11 and individuals with the largest education deficits tend to benefit more from this type of programming.12 Although participating in secondary-degree programs has been found to reduce recidivism by 30 percent,13 better results have often been observed for postsecondary education programming.14

While the literature has evaluated the impact of education programming on recidivism, it has also examined the effects on other important outcomes such as prison misconduct, post-release employment and return on investment (ROI). Although prior research has yielded mixed results regarding the impact of educational programming on prison misconduct,15 the literature has consistently shown that prison education improves post-release employment outcomes.16 Even though meta-analyses of prison education have generally reported modest reductions for recidivism, the ROI estimates have been relatively large. Indeed, research has reported a ROI of $19.62 for prison-based correctional education (basic and postsecondary) and $13.21 for vocational education.17

Employment Programming

Obtaining employment is, as noted earlier, challenging for those involved in the correctional system due to the relatively low levels of educational attainment and the presence of a felony conviction. Having a job, however, has been shown to reduce recidivism,18 and individuals are less likely to commit crimes when they have stable, full-time employment.19 To address this moderate criminogenic need, correctional systems frequently provide individuals with employment programming, including prison labor opportunities as well as participation in programs such as work release.

Having a job, however, has been shown to reduce recidivism, and individuals are less likely to commit crimes when they have stable, full-time employment.

The evidence suggests the effect of prison labor on recidivism is, at best, minimal. Although some research has reported that prison employment reduced recidivism,20 other studies have not found significant effects overall.21 Conversely, the impact of prison labor on prison misconduct and post-release employment has generally been favorable.22 The most recent evaluation found that people who spent a greater proportion of their overall confinement time working a job in prison had less misconduct, lower recidivism, and increased post-release employment.23 The results from a cost-benefit analysis of correctional programming reported a ROI of $4.74 for the prison industry.24

Within the U.S., correctional agencies have long relied on the use of prison work release programs, which allow participants who are near the end of their prison terms to work in the community and return to a correctional or community residential facility during nonworking hours. Although most of the existing evaluations are outdated, the most recent research indicates work release produces a significant, albeit modest, reduction in recidivism.25 Prior research has consistently found positive results for employment, with the most recent evaluation showing that work release significantly increased the odds that participants found a job, the total hours they worked, and the total wages they earned.26 Given these findings, prior research has reported a ROI of $11.19 for work release and a benefit of nearly $6,900 per participant.27 In addition, an evaluation of a work release program in Minnesota reported a cost avoidance of nearly $700 per participant for a total of $350,000 annually.28

Policy Implications

Access to legal employment is key to reducing recidivism and the post-prison social disabilities that returning citizens endure. Extensive research has documented the interaction between employment and increased educational attainment as pivotal to reducing an individual’s propensity to recidivate.29 Roughly 7.9 million people return to local communities from state prisons and local jails across the country each year.30 The status quo of fractious federal and state policies combined with insubstantial funding are incompatible with the enormity of reentry challenges.

Reducing employment barriers for returning citizens requires practitioners and policymakers to enact policies at a scale commensurate with the decarceration rate. State and federal policies must be aligned and braided into an overarching policy framework to synchronously address the interlocking issues citizens encounter on reentry. Increasing access to gainful employment for returning citizens relies on seamlessly articulating multi-jurisdictional policies into a coordinated strategy across three (3) critical pillars: workforce training, educational upgrading, and regulatory employment barriers.

Accordingly, our recommendations include:

Short-Term Reform

- Deepen Pell Grant Investments for Incarcerated Individuals

Medium-Term Reform

- Expand Pre-Release Workforce Development Services

Long-Term Reform

- Reform Employment-based Criminal Background Checks

SHORT-TERM REFORMS

Without a doubt, education and employment are linked. The approved COVID-19 Economic Relief legislation reinstated the Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated students. This legislation reversed approximately three decades of government-sanctioned educational segregation.

Included in this legislation, the government funded Pell Grant’s minimum eligibility requires applicants to have earned either a high school diploma or GED. Data shows that nearly two in three (64 percent) incarcerated adults have a high school credential, clearing the way for them to take advantage of the Pell Grant repeal.31 However, 30 percent of incarcerated adults have not earned a high school credential. As a result, these individuals are considered ineligible for the Pell Grant unless enrolled in a career pathway program. We believe the COVID-19 Economic Relief legislation’s revival of the Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated students will increase their access to postsecondary training. Yet it is too early to determine all of the legislation’s effect on inmates’ educational achievements.

There are important questions about the functional literacy levels of the incarcerated adult population. Incarcerated adults with a high school diploma or less have significantly lower numeracy literacy levels than the U.S. adult population. Attaining a high school credential does not necessarily correlate to functional literacy. According to Rampey and others, 43 percent of incarcerated adults with a high school credential have low literacy and numeracy rates. Literacy rates among incarcerated adults without a high school diploma were even more alarming; 79 percent of these adults had low numeracy and literacy rates.32 The implication of these abysmal literacy statistics is grave, especially when translated into functional competencies. Adults scoring below basic on OECD’s aptitude test can perform basic arithmetic and read relatively short primary printed texts. However, individuals with low aptitude scores are likely to encounter difficulties with higher-order cognitive reasoning tasks, including drawing low-level inferences or interpreting basic statistics (OECD, 2013).33 These disquieting figures point to systematic functional illiteracy challenges within the incarcerated population.

It is urgent that policymakers address systemic remedial educational needs along with increasing access to postsecondary education for incarcerated students and structural education gaps. The impact of functional literacy challenges can limit the effectiveness of policies aimed at expanding access to postsecondary educational programming. Evidence shows that participation in correctional educational programming can increase the probability of finding post-release employment.34 Furthermore, President Biden should commission a task force to study fundamental educational competencies, functional literacy, numeracy, and digital literacy levels of the incarcerated adult population. This task force should also have a national advisory board of experts to study structural deficiencies and propose recommendations for digitizing education programs, providing qualified educators, and increasing access to educational resources.

It is important to note that only upgrading educational quality will not increase access to employment for returning citizens. Generally, in the U.S. labor market, individuals with a high school diploma experience substantially higher unemployment rates than their peers with a college degree. In 2020, the unemployment rate of individuals with a high school diploma was 63.6 percent higher than that of college-educated persons with a bachelor’s degree.35 Furthermore, the tremendous earnings gap between workers based on educational attainment mirrors employment disparities. Workers a high school credential earned 40 percent lower median wages than those with a bachelor’s degree. Similarly, individuals with less than a high school diploma earned nearly 53 percent less than their college-educated peers.36 Altogether, these labor market statistics show the benefits of a college education. Additional supporting evidence from a RAND Corporation meta-study suggested that inmate access to occupational training coupled with academic training were associated with a 43 percent reduction in probability to recidivate.

Increasing access to quality academic education and occupational skills-based training that builds a skill base to meet the needs of the current labor market will significantly increase access to sustainable post-prison employment opportunities. Based on promising evaluation results, the Biden Administration should authorize the Department of Labor’s (DOL) expansion of its Pell Grant Short-Term Training experiments to include incarcerated adults. The DOL Pell experimental studies examined the impact of expanding Pell Grants’ use for occupational training and short-term training programs for underemployed individuals and unemployed individuals. Recently released findings were positive: post-bachelor participants were 36.7 percent more likely than nonparticipants to complete occupational training in high-demand fields, including health and information technology.

Increasing access to quality academic education and occupational skills-based training that builds a skill base to meet the needs of the current labor market will significantly increase access to sustainable post-prison employment opportunities.

Not only were similar results obtained in short-term occupational training lasting less than 15 weeks, but also students were 15 percentage points more likely to enroll in additional educational programs and eight percentage points more likely to complete training. In short-term occupational training programs, students selected trade skill pathways in transportation and materials moving, health professions, and construction. Strikingly, the program’s positive effects—enrollment and completion—were most pronounced for dislocated workers and those facing employment challenges.37

The debate surrounding the long-term employment and wage gains associated with short-term occupational training remains unsettled. Without credible data-driven evidence, questions about benefits for incarcerated adults will be even more contentious. Interactions between employment and adjacent barriers such as housing insecurity, lack of adequate transportation, and community supervision restrictions increase recidivism risk. The federal government should evaluate the efficacy of expanding the Pell Grant experiments on sustainable employment and wage quality. Additionally, the task force should examine the effects of applying the Obama-era Gainful Employment rule to experimental Pell programs to evaluate whether the accountability framework increases access to relevant, high-quality skill development training.

MEDIUM-TERM REFORMS

Expand Pre-Release Workforce Development Services

Policymakers should strive to align the timing of holistic services with expanded access to educational training to improve reentry success rates. It is essential to match policy that supports the intersecting barriers returning citizens face on reentry. The federal government should center the public workforce development system in policy responses aimed at improving quality employment outcomes for returning citizens. DOL’s now-dormant pilot, Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release (LEAP), is an excellent policy candidate. Through LEAP, DOL established 20 jail-based job training centers to link incarcerated adults to the workforce system during incarceration to strengthen their connection to the labor market and enhance their employment readiness.

LEAP provided robust evidence on the types of workforce development services that improve post-carceral employment outcomes using a continuity-of-care model centered on linking pre-release services to post-release employment supports. Upon conclusion, 85 percent of LEAP’s scattered-site participants had increased their workforce readiness level, as measured by observed outcomes or improvements in job readiness pre- and post-testing.38

Although LEAP sites failed to meet planned-retention and tracked-employment targets, program evaluators reasoned that data collection deficiencies may have contributed to systematic underreporting and resulted in deflated impact metrics. Despite data collection challenges, LEAP succeeded in reducing recidivism for program participants; evaluators reported an overall recidivism rate of 20 percent after one year of participants’ release. Roughly 75 percent of LEAP sites reported recidivism rates lower than the programmatic target of 22 percent.39

The favorable results for LEAP are consistent with other research that has evaluated the effectiveness of employment programming that is designed to provide a continuum of services that begins within the correctional facility and continues in the community following release. In an evaluation of Minnesota’s EMPLOY program, which provided participants with employment assistance 90 days prior to release from prison and continued for up to one year after release, the results showed that it significantly reduced rearrest by 35 percent. Program participants were also more likely to find and maintain a job after their release from prison than their comparison group counterparts, resulting in more total wages earned.40 Due to these results, a cost-benefit analyses revealed that EMPLOY generated a ROI of $6.45 for a total of $2.8 million in costs avoided annually.41

Despite LEAP’s promising results, structural barriers such as criminal background checks, conflicts with supervision requirements, and housing insecurity, among other issues, dampened the pilot’s employment and educational gains. Nonetheless, LEAP and EMPLOY provide a propitious proof of concept on siting pre-release workforce development services within the prisonsystem and leveraging strategic partnerships with external community-based organizations and correctional system decisionmakers to bolster the framework’s design. The federal government should reauthorize the LEAP pilot, build upon lessons learned, and fund the next iteration at a scale that increases the program’s impact.

LEAP’s reauthorization in conjunction with the First Step Act (reauthorization of the Second Chance Act) would weave crucial funding streams into a comprehensive policy response. In the final analysis, Second Chance Act (SCA) Adult Demonstration pilots showed that multijurisdictional funding supports and a follow-through-care approach to reentry increased employment outcomes and wages for program participants. Individuals included in the SCA treatment group were more likely to be employed and earned an average $1,800 more than nonparticipants; this wage differential represents a 70 percent improvement in employment earnings. Although the SCA program did not reduce the probability of recidivism, participants were more likely to report receiving cognitive behavioral therapy, housing support, and job search assistance.42

LONG-TERM REFORMS

Reform Employment-based Criminal Background Checks

Successfully reintegrating formerly incarcerated individuals depends on policymakers’ abilities to close structural remedial education gaps and increase access to high-quality occupational skills-based training. Inattention to the large number of fundamental employment barriers challenges the effectiveness of any policy intervention. Criminal background checks present substantial hurdles to gainful employment even for college-educated, justice-involved persons. Criminal background checks function like a double-edged sword. Research has found that employers who conducted criminal background checks were more likely to hire Black men.43 However, in the absence of background checks, employers overestimated the relationship between visible minority markers and criminality, leading them to statistically discriminate against Black men and those with weak employment records; these assumption patterns resulted in reduced employment opportunities.44 The intersection of criminal records and stigmatized perceptions of criminality amplifies the social disadvantage for justice-involved persons. In essence, having a criminal record poses considerable obstacles to returning citizens, especially those without a college degree.

After two decades of steady momentum across states and local municipalities, efforts to promote fair chance hiring culminated in the passage of the Fair Chance to Compete for Jobs Act of 2019.45 Research on the effects of ban-the-box policies is still emerging. However, several formative studies have shown counterproductive or de minimis effects of fair chance hiring policies on employment.46 Similarly, another study found that ban-the-box policies reduced the employment rate of individuals with criminal records by 2.4 percentage points.47 These studies, among others, suggest that well-intentioned fair chance hiring policies may lead to counterproductive effects that disadvantage intended beneficiaries, further muddying returning citizens’ employment landscape.

Employers’ growing and widespread use of algorithmic criminal background checks raise serious concerns about background check data, particularly as robust data protection regulations continue to lag behind market innovations. The algorithmic background-checking cottage industry is fraught with harmful data mining practices that frustrate individuals’ efforts to find gainful employment due to collateral data errors.48 Policymakers should target other consequential screening barriers, such as the accuracy of criminal records that have been shown to adversely affect employment prospects.

Recommendations for Future Research

We suggest three promising avenues for future research to extend what we know about education and employment programming effectiveness for correctional populations. First, policymakers should expand research efforts to deepen our understanding of pre-release training programs. These efforts should rely on rigorous evaluation methods, including randomized controlled trials.

Second, while interventions that provide a continuum of service delivery from the institution to the community have generally yielded the best employment and recidivism outcomes, future research should examine the extent to which a continuum of care improves outcomes compared to services delivered only in prison or in the community. Finally, future research should focus on the extent to which functional literacy and digital illiteracy rates stymie incarcerated persons’ educational attainment pursuits and weaken their connection to gainful employment. Moreover, researchers should focus on identifying intersectional solutions, including educational models, with the potential to reduce literacy barriers.

Conclusions

The employability of returning citizens is a moral imperative and should be a central focal point of the criminal justice reform agenda. Increased educational attainment and connections to employment moderate recidivism risk factors; however, unimodal interventions seldomly yield sustainable outcomes. Addressing employability alone ignores attendant social vulnerabilities that returning citizens experience; formerly incarcerated women, in particular, are susceptible to adverse outcomes. The understandable effect of collateral consequences of incarceration should inform the scope of reentry policies. Furthermore, rigorous evidence-based research and robust evaluation strategies must inform comprehensive reintegration reforms.

Beyond employment, incarcerated persons contend with a morass of social and legal barriers that compound the social disadvantage of a felony label and increase recidivism risk.49 Adopting an interdisciplinary approach to reentry policy formulation is critical to resolving crucial disconnects, reduce social exclusion, and improve post-prison employment outcomes for returning citizens.

Recommended Readings

Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that

Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Bellotti, Jeanne, Samina Sattar, Alix Gould-Werth, Jillian Berk, Ivette Gutierrez, Jillian Stein, Hannah Betesh, Lindsay Ochoa, and Andrew Wiegand. Developing American Job Centers in Jails: Implementation of the Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release (LEAP) Grants. Rep. Washington: U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Chief Evaluation Office, 2018. Print.

Davis, L.M., Bozick, R., Steele, J.L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J.N.V. (2013). Evaluating the

Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Duwe, G. (2018). The Effectiveness of Education and Employment Programming for Prisoners.

American Enterprise Institute: Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-effectiveness-of-education-and-employment-programming-for-prisoners/.

Middlemass, Keesha. Convicted and Condemned: The Politics and Policies of Prisoner Reentry. New York: New York UP, 2017. Print.

-

Footnotes

- Duwe, Grant and Valerie Clark (2014). The effects of prison-based educational programming on recidivism and employment. The Prison Journal, 94, 454–478.

- Ryan, C.L., & Bauman, R. (2016). Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015. United States Census Bureau, 2015.

- Berstein, J., and Houston, E. (2000). Crime and Work: What We Can Learn from the Low-Wage Labor Market. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute.

- Duwe, G., & Clark, V. A. (2017). Nothing will work unless you did: The predictors of post-prison employment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44, 5, 657–677; Kling, J. (2006). Incarceration length, employment and earnings. American Economic Review, 96, 863–76; Lalonde, R. J., & Cho, R. M. (2008). The impact of incarceration in state prison on the employment prospects of women. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24, 243–265; Pettit, B., & Lyons, C. (2002). The Consequences of incarceration on employment and earnings: Evidence from Washington State. Unpublished manuscript; University of Washington: Seattle, WA; Sabol, W. (2007). Local labor-market conditions and post-prison employment experiences of offenders released from Ohio state prisons. In S. Bushway, M. Stoll, & D. Weiman (Eds.), Barriers to reentry? The labor market for released prisoners in post-industrial America (pp. 257–303). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Duwe, G., & Clark, V. A. (2017). Nothing will work unless you did: The predictors of postprison employment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44, 5, 657–677; Lalonde, R. J., & Cho, R. M. (2008). The impact of incarceration in state prison on the employment prospects of women. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24, 243–265.

- Kling, J. (2006). Incarceration length, employment and earnings. American Economic Review, 96, 863–76; Pettit, B., & Lyons, C. (2002). The Consequences of incarceration on employment and earnings: Evidence from Washington State. Unpublished manuscript; University of Washington: Seattle, WA; Sabol, W. (2007). Local labor-market conditions and post-prison employment experiences of offenders released from Ohio state prisons. In S. Bushway, M. Stoll, & D. Weiman (Eds.), Barriers to reentry? The labor market for released prisoners in post-industrial America (pp. 257–303). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Farrington, D.P. (2005). Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(3):177–190; Hagan, J., and McCarthy, B. (1997). Intergeneratioal sanction sequences and trajectories of street-crime amplification. In Gotlib, I.H. and Wheaton, B. (eds.) Stress and Adversity over the Life Course: Trajectories and Turning Points, pp. 73–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Huizinga, D., Loeber, R., Thornberry, T.P., and Cothern, L. (2000). Co-Occurrence of Delinquency and Other Problem Behaviors. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Maguin, E., and Loeber, R. (1996). Academic performance and delinquency. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, vol. 2, edited by M. Tonry. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Andrews, D.A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, S.J. (2006). The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime & Delinquency, 52, 7–27.

-

Adams, K., Bennett, K.J., Flanagan, T.J., Marquart, J.W., Cuvelier, S.J., Fritsch, E., Gerber, J.,

Longmire, D.R., and Burton, V.S. (1994). A Large-Scale Multidimensional Test of the Effect of Prison Education Programs on Offenders’ Behavior. The Prison Journal, 74(4), 433–449; Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; Wilson, D.B., Gallagher, C.A., & MacKenzie, D.L. (2000). A meta-analysis of corrections-based education, vocation, and work programs for adult offenders. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 37, 347–368. -

Davis, L.M., Bozick, R., Steele, J.L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J.N.V. (2013). Evaluating the

Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. - Pompoco, A., Wooldredge, J., Lugo, M., Sullivan, C., & Latessa, E. (2017). Reducing inmate misconduct and prison returns with facility education programs. Criminology & Public Policy.

-

Adams, K., Bennett, K.J., Flanagan, T.J., Marquart, J.W., Cuvelier, S.J., Fritsch, E., Gerber, J.,

Longmire, D.R., and Burton, V.S. (1994). A Large-Scale Multidimensional Test of the Effect of Prison Education Programs on Offenders’ Behavior. The Prison Journal, 74(4), 433–449. - Davis, L.M., Bozick, R., Steele, J.L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J.N.V. (2013). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Duwe, Grant and Valerie Clark (2014). The effects of prison-based educational programming on recidivism and employment. The Prison Journal, 94, 454–478; Kim, R.H., & Clark, D. (2013). The effect of prison-based college education programs on recidivism: Propensity Score Matching approach. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 196–204.

- French, S.A., & Gendreau, P. (2006). Reducing prison misconducts: What works! Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33, 185–218; Pompoco, A., Wooldredge, J., Lugo, M., Sullivan, C., & Latessa, E. (2017). Reducing inmate misconduct and prison returns with facility education programs. Criminology & Public Policy; Steiner, B., & Wooldredge, J. (2014). Sex differences in the predictors of prisoner misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41, 433–452.

- Cho, R.M., & Tyler, J.H. (2013). Does prison-based adult basic education improve postrelease outcomes for male prisoners in Florida? Crime & Delinquency, 59, 975–1,005; Davis, L.M., Bozick, R., Steele, J.L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J.N.V. (2013). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; Duwe, Grant and Valerie Clark (2014). The effects of prison-based educational programming on recidivism and employment. The Prison Journal, 94, 454–478.

-

Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that

Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy. - Skardhamar, T. & Telle, K. (2012). Post-release employment and recidivism in Norway. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 629–649.

- Crutchfield, R.D., & Pitchford, S.R. (1997). Work and crime: The effects of labor stratification. Social Forces, 76, 93–118; Uggen, C. (1999). Ex-offenders and the conformist alternative: A job quality model of work and crime. Social Problems, 46, 127–151.

-

Saylor, W.G., & Gaes, G.G. (1997). Training inmates through industrial work participation and

vocational apprenticeship instruction. Corrections Management Quarterly, 1, 32–43. - Duwe, G. & McNeeley, S. (2018). The Effects of Prison Labor on Institutional Misconduct, Post-Prison Employment, and Recidivism. Corrections: Policy, Practice and Research; Maguire, K. E., Flanagan, T. J., & Thornberry, T. P. J. (1988). Prison labor and recidivism. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 4, 3–18; Richmond, K.M. (2014). The impact of federal prison industries employment on the recidivism outcomes of female inmates. Justice Quarterly, 31, 719–745.

-

Duwe, G. & McNeeley, S. (2018). The Effects of Prison Labor on Institutional Misconduct,

Post-Prison Employment, and Recidivism. Corrections: Policy, Practice and Research; Gover, A.R., Perez, D.M., & Jennings, W.G. (2008). Gender differences in factors contributing to institutional misconduct. The Prison Journal, 88, 378–403; Saylor, W.G., & Gaes, G.G. (1997). Training inmates through industrial work participation and

vocational apprenticeship instruction. Corrections Management Quarterly, 1, 32–43; Steiner, B., & Wooldredge, J. (2014). Sex differences in the predictors of prisoner misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41, 433–452. - Duwe, G. & McNeeley, S. (2018). The Effects of Prison Labor on Institutional Misconduct, Post-Prison Employment, and Recidivism. Corrections: Policy, Practice and Research.

- Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

- Drake, E. (2007). Does Participation in Washington’s Work Release Facilities Reduce Recidivism? Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; Duwe, G. (2014). An outcome evaluation of a work release program: Estimating its effects on recidivism, employment, and cost avoidance. Criminal Justice Policy Review. DOI: 10.1177/0887403414524590.

- Duwe, G. (2014). An outcome evaluation of a work release program: Estimating its effects on recidivism, employment, and cost avoidance. Criminal Justice Policy Review. DOI: 10.1177/0887403414524590.

- Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy;

- Duwe, G. (2014). An outcome evaluation of a work release program: Estimating its effects on recidivism, employment, and cost avoidance. Criminal Justice Policy Review. DOI: 10.1177/0887403414524590.

- Nally J. et al. 2012. Post-Release Recidivism and Employment among Different Types of Released Offenders. Official Journal of the South Asian Society of Criminology and Victimology (SASCV) ISSN: 0973-5089 January–June 2014. Vol. 9 (1): 16–34.

- McKernan, Patricia. “Homelessness and Prisoner Reentry: Examining Barriers to Housing Stability and Evidence-Based Strategies That Promote Improved Outcomes.” Journal of Community Corrections, 2017, pp. 7–26.

-

Rampey, B. D., Keiper, S., Mohadjer, L., Krenzke, T., Li, J., Thornton, N., & Hogan, J. (2016).

Highlights from the U.S. PIAAC Survey of incarcerated adults: Their skills, work experience, education, and training: program for the international assessment of adult competencies: 2014 (NCES 2016-040). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ pubsearch -

Rampey, B. D., Keiper, S., Mohadjer, L., Krenzke, T., Li, J., Thornton, N., & Hogan, J. (2016).

Highlights from the U.S. PIAAC Survey of incarcerated adults: Their skills, work experience, education, and training: program for the international assessment of adult competencies: 2014 (NCES 2016-040). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ pubsearch - OECD (2019), Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f029d8f-en.

- Davis, L.M., Bozick, R., Steele, J.L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J.N.V. (2013). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- “Unemployment Rate 2.0 Percent for College Grads, 3.8 Percent for High School Grads in January 2020: The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-2-percent-for-college-grads-3-8-percent-for-high-school-grads-in-january-2020.htm#:%7E:text=Unemployment%20rate%202.0%20percent%20for,school%20grads%20in%20January%202020&text=The%20national%20unemployment%20rate%20was,people%20age%2016%20and%20older.

- “Unemployment Rates and Earnings by Educational Attainment: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov/emp/chart-unemployment-earnings-education.htm.

- Thomas, Jamie, Naihobe Gonzalez, Nora Paxton, Andrew Weigand, and Leela Hebbar. The Effects of Expanding Pell Grant Eligibility for Short Occupational Training Programs: Results from the Experimental Sites Initiative. Rep. Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences, 2020. Print.

- Bellotti, Jeanne, Samina Sattar, Alix Gould-Werth, Jillian Berk, Ivette Gutierrez, Jillian Stein, Hannah Betesh, Lindsay Ochoa, and Andrew Wiegand. Developing American Job Centers in Jails: Implementation of the Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release (LEAP) Grants. Rep. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor Chief Evaluation Office, 2018. Print.

- Bellotti, Jeanne, Samina Sattar, Alix Gould-Werth, Jillian Berk, Ivette Gutierrez, Jillian Stein, Hannah Betesh, Lindsay Ochoa, and Andrew Wiegand. Developing American Job Centers in Jails: Implementation of the Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release (LEAP) Grants. Rep. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor Chief Evaluation Office, 2018. Print.

-

Duwe, G. (2015). The benefits of keeping idle hands busy: The impact of a prisoner reentry

employment program on post-release employment and offender recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 61, 559-586. -

Duwe, G. (2013). What Works with Minnesota Prisoners: A Summary of the Effects of

Correctional Programming on Recidivism, Employment and Cost Avoidance. Minnesota Department of Corrections: St. Paul, MN. - D’Amico, Ronald, and Hui Kim. Evaluation of Seven Second Chance Act Adult Demonstration Programs: Impact Findings at 30 Months. Rep. Washingon, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2018. Print.

- Holzer, Harry J., et al. “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers.” The Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 49, no. 2, 2006, pp. 451–80. Crossref, doi:10.1086/501089.

- Holzer, Harry J., et al. “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers.” The Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 49, no. 2, 2006, pp. 451–80. Crossref, doi:10.1086/501089.

- Avery, Beth, and Han Lu. Ban the Box U.S. Cities, Counties, and States Adopt Fair-Chance Policies to Advance Employment Opportunities for People with Past Convictions. Rep. New York: National Employment Law Project, 2020. Print.

- Rose, Evan K. “Does Banning the Box Help Ex-Offenders Get Jobs? Evaluating the Effects of a Prominent Example.” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 39, no. 1, 2021, pp. 79–113. Crossref, doi:10.1086/708063.

- Jackson, Osborne and Zhao, Bo, The Effect of Changing Employers’ Access to Criminal Histories on Ex-Offenders’ Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from the 2010–2012 Massachusetts Cori Reform (2017-02-01). FRB of Boston Working Paper No. 16-30, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2942005

- Lapowsky, Issie. “Locked out of the Gig Economy: When Background Checks Get It Wrong.” Protocol The People, Power and Politics of Tech, 29 Apr. 2020, www.protocol.com/checkr-gig-economy-lawsuits. United States District Court Northern District of California. Jose Montanez V. Checkr, Inc. 29 June 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCOURTS-cand-4_19-cv-07776/pdf/USCOURTS-cand-4_19-cv-07776-0.pdf

- Middlemass, Keesha M. Convicted and Condemned: The Politics and Policies of Prisoner Reentry. NYU Press, 2017.

Longmire, D.R., and Burton, V.S. (1994). A Large-Scale Multidimensional Test of the Effect of Prison Education Programs on Offenders’ Behavior. The Prison Journal, 74(4), 433–449; Aos, S. & Drake, E. (2013). Prison, Police and Programs: Evidence-based Options that Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; Wilson, D.B., Gallagher, C.A., & MacKenzie, D.L. (2000). A meta-analysis of corrections-based education, vocation, and work programs for adult offenders. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 37, 347–368.

Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Longmire, D.R., and Burton, V.S. (1994). A Large-Scale Multidimensional Test of the Effect of Prison Education Programs on Offenders’ Behavior. The Prison Journal, 74(4), 433–449.

Reduce Crime and Save Money (Doc. No. 13-11-1901). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

vocational apprenticeship instruction. Corrections Management Quarterly, 1, 32–43.

Post-Prison Employment, and Recidivism. Corrections: Policy, Practice and Research; Gover, A.R., Perez, D.M., & Jennings, W.G. (2008). Gender differences in factors contributing to institutional misconduct. The Prison Journal, 88, 378–403; Saylor, W.G., & Gaes, G.G. (1997). Training inmates through industrial work participation and

vocational apprenticeship instruction. Corrections Management Quarterly, 1, 32–43; Steiner, B., & Wooldredge, J. (2014). Sex differences in the predictors of prisoner misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41, 433–452.

Highlights from the U.S. PIAAC Survey of incarcerated adults: Their skills, work experience, education, and training: program for the international assessment of adult competencies: 2014 (NCES 2016-040). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ pubsearch

Highlights from the U.S. PIAAC Survey of incarcerated adults: Their skills, work experience, education, and training: program for the international assessment of adult competencies: 2014 (NCES 2016-040). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ pubsearch

employment program on post-release employment and offender recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 61, 559-586.

Correctional Programming on Recidivism, Employment and Cost Avoidance. Minnesota Department of Corrections: St. Paul, MN.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).