The Vitals

Opioids are a class of drugs that affect the brain, including by relieving pain, and they are extremely addictive. Policymakers can combat the opioid epidemic by:

- limiting inappropriate use of prescription opioids;

- reducing the flow of illicit opioids (like heroin);

- helping people seek treatment for opioid misuse; and

- deploying harm reduction tools that blunt the risks of death, illness, or injury.

These strategies are reflected in ongoing work at the federal, state, and local levels.

-

130 Americans die from an opioid overdose every day, and millions of Americans report misuse of opioids.

-

Policymakers can combat the epidemic by reducing the number of people who receive prescription opioids and reducing the volume of prescription and non-prescription opioids released into communities.

-

Addressing the opioid epidemic requires helping the millions of Americans who are misusing opioids today by making treatment more widely available and using harm reduction strategies.

A Closer Look

Opioids

include prescription drugs like oxycodone as well as illicit drugs like heroin.

These drugs are extremely addictive. While opioids have existed for hundreds of

years, health care providers generally limited their use because of concerns about

addiction. However, beginning in the 1990s, a constellation of factors

led to increased use of prescription opioids, including growing attention to pain

management as an important clinical goal and the manufacture and marketing of a

new generation of prescription opioids. The rise in prescriptions was also associated

with increased availability of illegal opioids like heroin.

We

have seen a dramatic rise in illness and death associated with improper use of opioids.

According to federal data:

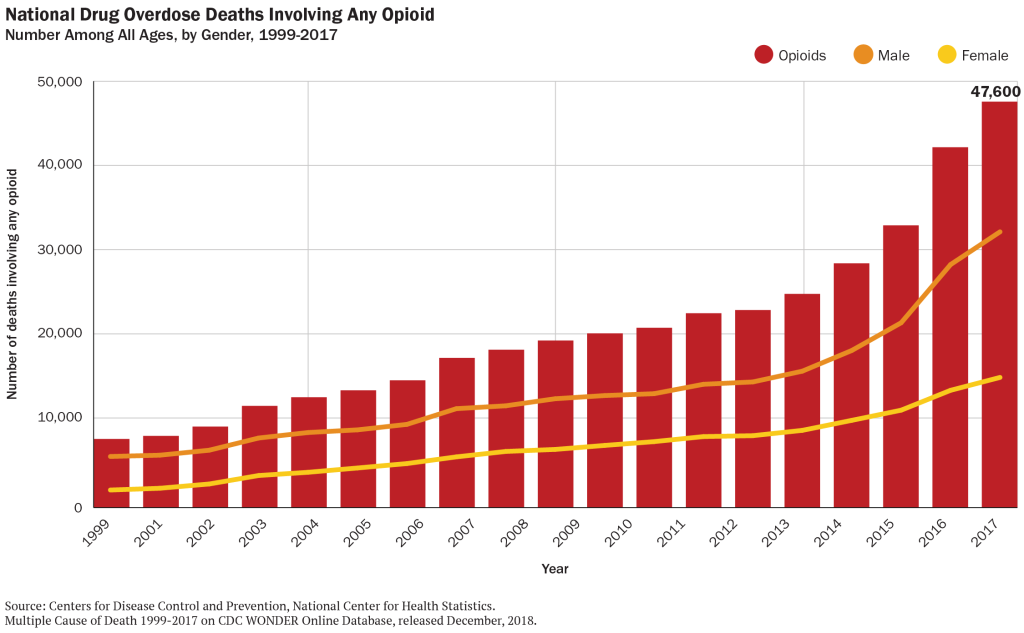

- 12 million people reported misuse of opioids in 2016.

- Estimates suggest that 2.1 million people struggled with opioid use disorder in 2017.

- Doctors wrote 59 opioid prescriptions per 100 residents in 2017, down from a peak of about 81 per 100 residents in 2010.

- There were 140,000 visits to an emergency room because of an opioid overdose in 2015.

- About 48,000 people died from an opioid overdose in 2017, or about 130 people per day.

For context, the number of deaths from opioid overdose in 2017 is comparable to the number of deaths from HIV-related causes at the height of that epidemic in the 1990s, and is nearly 8 times larger than the number of HIV deaths today.

What can policymakers do to combat the opioid epidemic?

Addressing

a public health crisis of this magnitude is a complex undertaking. Policymakers

can work to prevent people from becoming addicted to opioids and to help people

who are already misusing opioids to treat their addiction and minimize the risk

of death or other harm. In general, there are four kinds of strategies:

Limiting prescription opioids

For

the last 15 years, physicians have been prescribing opioids at high rates. In a

handful of states, there is more

than one opioid prescription per person each year. Some overprescribing

is the result of “pill mills”—unethical providers who write prescriptions with indifference

to clinical need. Other times, patients may be visiting multiple prescribers to

seek prescription opioids. And in still other cases, providers may be using prescription

opioids to combat pain when other treatments, smaller quantities, or less potent

drugs may suffice.

The

overuse of prescription opioids fuels the epidemic in two ways. First, it introduces

patients (even when taking these drugs as prescribed) to an addictive substance,

which creates the risk of subsequently developing opioid use disorder. Second, it

creates a flow of opioids that can be diverted from their intended purpose.

Therefore,

policymakers can take actions that reduce opportunities for misuse of prescription

opioids. These include:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs).

49

states and the District of Columbia have established a PDMP, a statewide

database that shows every opioid prescription. Health care providers can check (or

be required to check) this database before writing a prescription, allowing them

to see if the patient has received opioids from other doctors.

- Prescriber limits. In 2016 the federal government released guidelines for prescribing opioids

for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life

care. Consistent with these guidelines, many

states have made it unlawful for providers in many circumstances to write

opioid prescriptions that exceed a particular strength or that span longer than

a few days or weeks.

- Law enforcement. Cracking down on “pill mills”

and other unethical and illegal overprescribing behavior by health care providers

can have a major impact on the volume of prescription opioids.

- Stakeholder education. Provider education can emphasize

the appropriate and limited role of opioids. Similarly, insurance companies can

be encouraged to cover non-drug pain therapies and to monitor their own data for

early warning signs of opioid misuse or prescriber misconduct.

All of these strategies must balance opioids’ valuable benefits in pain control against the risk of misuse. Policymakers should always be cognizant of the possibility that they could enact too many or the wrong kinds of restrictions and leave patients unnecessarily struggling with unmanaged pain.

Reducing the flow of illicit opioids

Many

opioid deaths are associated with illicit opioids like heroin and illegally produced

fentanyl. (Fentanyl, in particular, is an extremely potent and deadly opioid, and

its use is on the rise.)

Although there are no simple solutions,

many communities have invested in funding for law enforcement efforts that target

large scale opioid distribution.

Collaborative

efforts that work across borders and jurisdictions are necessary to share up-to-date

information. The federal government has helped facilitate

intelligence sharing across agencies, which can help federal, state, and local law

enforcement identify and respond to emerging trends. Federal law enforcement agencies

have also brought cases against major drug trafficking organizations using this

shared information.

In

addition, communication among law enforcement, public health professionals, and

first responders about distribution patterns can help target public health efforts.

Promoting

treatment

A

variety of treatment options exist to help people already suffering from opioid

use disorder. Experts

believe that the most effective treatment for many people will be “medication

assisted treatment,” or MAT. MAT involves taking one or more drugs that are intended

prevent opioid misuse. These drugs can reduce cravings for opioid misuse or prevent

opioids from causing a “high.” (Some of the drugs involved in MAT are themselves

opioids.) MAT also involves structured counseling and other support.

Only

17.5%

of people who could benefit from specialized treatment for prescription opioid use

disorder received it in 2016. Obstacles to treatment include lack of insurance coverage

for treatment, difficulty finding a provider, and patients’ unwillingness to begin

treatment. Strategies to promote treatment include:

- Medicaid expansion. In states that have expanded

Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act , any low-income individual can enroll in

Medicaid, where they will have coverage for a wide variety of opioid treatment options.

Many

studies

have linked Medicaid expansion to improved take-up of MAT therapies. Therefore,

in states that have not yet expanded, Medicaid expansion can help many people access

treatment.

- Payments for opioid treatment. Policymakers can

also provide funding for opioid treatment for people who are uninsured or underinsured.

This can include supporting treatment directly (like paying for MAT therapies) or

subsidizing services like housing support that can make treatment more successful.

- Expanding treatment capacity. Communities can invest in training providers to treat opioid use disorder or supporting the development of new treatment facilities or modalities. Policymakers may also wish to consider updates to policies about how physicians can become certified to prescribe MAT.

- Peer support. There are many successful models

of peer support interventions where people in treatment help encourage others with

opioid use disorder initiate treatment and offer support throughout recovery. Peer

supports can bridge the gap between the clinical treatment setting and everyday

life.

- Treatment and the criminal justice system. The

federal government has also recently released new guidance

to states on MAT in the criminal justice system, suggesting that criminal

justice agencies may choose to provide MAT in-house, or partner with community-based

providers to deliver treatment to voluntary participants in custody. Establishing

relationships with community-based providers can help ensure continuity of care

once individuals have been released from incarceration.

The

federal

government has provided significant grants to states, and states and

local communities are also investing their own resources in these kinds of treatment

strategies. Policymakers may also recognize that injury and death associated

with opioid use has been concentrated in communities experiencing lower

rates of economic growth, which can help target treatment

investments.

Reducing

harm

Finally,

policymakers can also focus on “harm reduction” – that is, mitigating the risk that

opioid use disorder will cause illness, injury, or death. This includes:

- Naloxone. One of the most important tools is broad

availability of naloxone, a drug that can immediately reverse the effects of an

opioid overdose. Making naloxone widely available to first responders (including

police officers) and to individuals can

dramatically

reduce the risk of death from overdose.

- Prisons and jails. Individuals recently released

from prison are 40

times more likely than others to die of opioid overdose. Making naloxone

available to individuals about to be released from incarceration can be a particularly

impactful harm reduction strategy.

- Needle exchange. Opioid misuse often involves intravenous

drug use, which can lead to transmission of infections like HIV and Hepatitis C.

Making clean needles available can reduce the risk of these diseases, and can connect

drug users with vital

health care services. Needle exchange programs can also link individuals

with opioid use disorder to treatment services when they are ready to seek treatment.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How do we tackle the opioid crisis?

October 18, 2019