In this episode of Foresight Africa podcast, Ruth Kagia, senior fellow at Results for Development and former country director for Southern Africa at the World Bank, discusses the risks and opportunities of STEM education in Africa. She explains ways that young girls and women can enter STEM-related fields and more broadly how to address “learning poverty” on the continent.

- Subscribe and listen to Foresight Africa on Apple, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

TRANSCRIPT

[music]

ORDU: I’m Aloysius Uche Ordu, director of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. And this is Foresight Africa podcast.

Since 2011, the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings has published a high-profile report on the key events and trends likely to shape affairs in Africa in the year ahead. Entitled Foresight Africa, the goal of the publication is to bring attention to these burning issues and to support policy actions to address them.

This is season two of the Foresight Africa podcast in which I engage with the report authors, as well as policymakers, industry leaders, Africa’s youths, and other key figures. Learn more on our website, Brookings dot edu slash Foresight Africa podcast.

My guest today is Mrs. Ruth Kagia. Ruth spent over two decades in senior management positions at the World Bank, including as global director for education and country director for Southern Africa. She returned home to Kenya and was appointed to an influential position as deputy chief of staff and senior adviser, policy and strategy for the former president of Kenya, H.E. President Uhuru Kenyatta. Ruth wrote a brilliant essay for Foresight Africa 2023 titled, “STEM Education in Africa: Risk and Opportunity.” She graciously agreed to be on our panel when we launched Foresight Africa recently in Nairobi. Sister Ruth, a very warm welcome to the show.

KAGIA: Thank you very much, my brother, Aloysius.

ORDU: Shall we start then with for the benefit of our listeners—and we’re delighted that many, many, many of our listeners now coming from many countries across the continent and elsewhere in the world—and for their benefit, could you tell us a little bit about your journey, what you did prior to embarking on your distinguished career in international development at the World Bank?

KAGIA: Thank you. Before joining the World Bank three intersecting experiences in a sense led me almost inevitably to the World Bank. The first is one of the very first jobs that I did in research was a very large scale, privately funded research program looking at the impact of socializing practices on the future growth and behavior practices of children. And what that experience gave me is some unique insights into the critical role of mothers in shaping the lives of their children.

The second experience was when I taught in several girls’ high schools. And again, that left me with a deep impression of, one, the sorting mechanism of education and how education message particularly at high school during adolescence sorts young people into the good, the bad, and the ugly, if you like. I have tracked many of those young women through life and the veracity of that observation remains very strong.

But in teaching young women, I saw the energy, the vision, the dreams that young people have when those are well harnessed. But I also witnessed at a very close range the risks that adolescents have, even buried one girl who died as she was trying to procure an abortion.

So, just seeing the experiences of how the future is held in the hearts of teachers again was a critical marker in my career.

And then the third one was that I got a political appointment by the then President Moi way back in ‘86. And what that did was to propel me into high-level policymaking, into beginning to understand how you translate ideas into policy and practice at the highest level. And the convergence of those three experiences was how intertwined development is between the social, the political, and the economic.

ORDU: Very few people I know would have had such an auspicious convergence, if you like, of a trinity of events that shaped you and prepared you for a career in international development. Ruth, after the career you’ve had, right, some people would have returned home and just retired, but not you. In your case, you returned to Kenya and you landed in the inner circle of policymaking under the President H.E. Kenyatta. How did that come about?

KAGIA: Believe it or not, Aloysius, this was pure serendipity. I knew of President Kenyatta a little bit from working at the World Bank when he was finance minister. And when I came and he found out that I had retired, he told me that you really can’t retire, we need to utilize your international experience. And President Kenyatta is, you know, of one of the most visionary leaders in Africa, recognized the importance of putting Kenya on the global map, of attracting investments into Kenya, and the importance, therefore, of bringing in international experience to bear on realizing that vision. And in me, he saw the bigger possibility of my helping him realize that vision.

So, it was a meeting of minds. I was honored to be able to give back to the country that had supported me to grow into the high levels of the international arena, and this was a unique opportunity to give back. So I did not say no, I did not even ask, what what would you like me to do? I just said, when do you want me to start?

ORDU: Difficult to say no to such an offer, right?

KAGIA: It is. It was a tremendous privilege.

ORDU: Right. Especially working closely to one of Africa’s greatest visionaries, President Kenyatta. Before all this, at some point, you wrote a book titled Balancing the Development Agenda: The Transformation of the World Bank under James D. Wolfensohn, 1995–2005. What motivated you to write the book and what were some of the key findings in that book?

KAGIA: In many ways, we are all products of our history. Part of the reason why I ended up working for President Moi at such a high level was because he was having a lot of difficulty with the Bretton Woods institutions. They were clashing over governance issues. They were clashing over the way he was sort of utilizing the resources available. And the Bretton Woods institutions were so dictatorial that if they said you can’t do something, you wouldn’t be able to do it and none of the other partners would be able to release funds to you.

So, I was brought into his office partly to help broker dialogue between Kenya and the Bretton Woods institutions. So, when the Bank began to face issues of 50 years is enough, a lot of questions about the relevance of the Bank, the dictatorial approach of the World Bank to to countries, part of the response was to begin to bring in people from the social sectors to balance the overly economic focus of the World Bank.

So, I came in when the Bank was very, very unpopular. Then Jim Wolfensohn joined the World Bank in ‘95. And almost immediately we began to see finally somebody who was willing to listen to the concerns of developing countries. And I watched him over the next decade as he literally turned the institution around completely , focusing on the client, focusing on results, understanding that development is not monolithic. We cannot just look at the economic elements. So, putting the Bank on two legs: investment in people and investment in growth, recognize the interdependence of all of us, therefore leveraging partnerships.

I saw that transformation at very close range. And for me, having experienced it firsthand in Kenya and beginning to see the Bank finally beginning to listen to the side of the client for me it was very personal and very meaningful because I saw how an important institution can be a force of good or a force of evil, so to speak.

Therefore, as Jim Wolfensohn came to the end of his tenure in 2005, and it was proposed that we need to record that huge transformation that had taken place, I did not hesitate to lead the exercise. It is one of the most meaningful that I have done. Basically, just it was watching change and history being made right in front of your eyes.

ORDU: In fact, history was definitely made since the World Bank opened its doors in June 25, 1946. In my own reckoning, there has been three really, really transformational presidents of the World Bank of the 14 or so that have served. I think Eugene Black was just a phenomenal president. I think that Robert McNamara was absolutely a phenomenal president. And of course, of course, Jim Wolfensohn I think Jim really, really vastly expanded the remit of the Bank and basically reformed it to good effect. And Africa benefited tremendously under his leadership. It was great of you to pay tribute to him in that way.

KAGIA: Exactly. And if I may say so, Aloysius, the Bank is at that point, it was in ‘95, as we speak, with the influx of private capital, with a multiplicity of development institutions, the Bank really needs to do another Jim Wolfensohn moment and think where do they fit in the global development arena.

ORDU: I couldn’t agree more. In the nation’s capital throughout the spring meetings 2023, I think the debate is on as to which direction the institution should go. And as you and I know, there is no shortage, there is no shortage of what people are telling the Bank to do. Nobody ever says, drop this or drop that. Everybody’s adding on to the list of what the Bank should do. It’s going to be interesting to see how things unfold under a new leadership of Ajay Banga.

KAGIA: Indeed, indeed.

ORDU: Yeah, right. So, Ruth, you coauthored a blog, “Investing in sexual and reproductive health paves the way for healthier families and stronger economies.” What were your key conclusions in that blog?

KAGIA: We did that stimulated by the concern that, on one hand, we all recognize the centrality of women in development. We recognize that women are the gateway to family and child health. We recognize that women hold half of the sky. But when we look at key investments that should be made to realize that potential, we found there were, they were missing in critical areas, particularly on women’s health. And globally over 200 million women do not have access to family-planning methods, so they cannot plan their families. More than 40 million do not give birth in a health facility. Over 20 million do not get health care support when they develop pregnancy related complications. Another 20 million don’t get medicines to prevent mother-to-child transmission, and so on.

So, when we look at critical women health issues, we found it was lacking in an adequate response. And that in essence was jeopardizing the mother’s health, but more critically jeopardizing the future of children who either die before five years old or grow up with deficiencies or disabilities that would impair their long-term productivity.

So this blog was against that context, that for only $25 per woman, you can address all these issues, secure the health of the woman, secure the health of the child. And we looked at countries that had provided sufficient contraceptives, provided sufficient maternal care, and you could see the difference. Kenya was … is an example in point where we have seen, for example, because of increased availability of family planning support, 70% of women have that, fertility has declined from about 6.7% in ‘89 to 3.4 in 2022. That’s dramatic. It means women have the choice to have the size of family that they require and all that goes with it in terms of improving child health.

But we also found, and that continues to be a major concern even today, that teenage pregnancies, early marriages by young women are in essence putting a brake on the potential of young women. The most recent demographic and health survey in Kenya, which was released in January, demonstrated that 15% of 15- to 19-year-olds in Kenya have been pregnant, and in one county, Samburu, as much as 50%. That is phenomenal. That means that you’re losing about half of your young women even before they start their lives. So the, the rationale behind this blog was to sound the alarm on a best-buy: just invest in the health of women and girls, and we are investing in the future.

ORDU: I find it astonishing, Ruth, that poorer countries all over the world are giving women opportunities to control their own destiny and their own bodies. Yet here in the United States of America, who would have who would have thought the richest country on the planet, you know, and the political momentum is inextricably to control women’s bodies. I mean, it just it’s incredible. Absolutely unbelievable.

KAGIA: That’s a story for another day.

ORDU: Indeed, a story for another day. But it provides us a very, very excellent segue, Ruth, to pivot to your brilliant essay for us in Foresight 2023. You open that essay with a quote from former President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. Nkrumah, in his statement when the OAU was founded in 1963, when he said, “it is within the possibility of science and technology to make even the Sahara bloom into a vast field and verdant vegetation for agricultural and industrial development.” Ruth, what inspired you to open with this brilliant quote?

KAGIA: What inspired me was the COVID experience. Because what I saw during those two years of COVID is how, when faced with a crisis that seemed almost insurmountable, when African countries realized that they are last in the queue in getting vaccines, they came together and they established the Africa Medical Platform that basically helped them secure the needed pharmaceuticals for to respond to COVID in a way they wouldn’t have been able to do it if they had acted on their own.

But for me, what that awakened is a reminder of the vision of the ‘60s when these countries were becoming important and the very clear sense of direction our leaders then had about where they would like to take Africa. But I think as things improved, everybody sort of went to their own spaces. And that unanimity of vision and unanimity of purpose in essence receded into the background until COVID hit. So, that is what in essence stimulated it. It’s a reminder that when you have a single-minded focus on an issue that unites us as a continent, there is nothing that we cannot overcome.

ORDU: Fascinating indeed. You also wrote, Ruth, that STEM education—STEM meaning science, technology, engineering, and maths education landscape in Africa—is characterized by risk and opportunity. What are some of these risks and inherent opportunities that you’ve observed?

KAGIA: I find when we talk about Africa on such critical issues, it is the classical case of half empty, half full glass. There are huge risks, mainly associated with resources, inadequate financing for science education to get the facilities. Once you have the facilities, maintaining them in a functional level in terms of equipment, some of which is renewable, and there isn’t enough recurrent expenditure. Resources to train teachers in such a specialized area because countries tend to be overwhelmed by the numbers. And when it comes to specialized areas, those are the ones that suffer.

But even as I say that, I get excited by the level of entrepreneurial and innovation energy I see in the continent. Look at any international competition, whether it is in technology related or science related, and there’ll be several Africans there. Quite often Kenyans, I dare say.

But the point is, imagine several green shoots of innovation and creativity that almost defies the poverty of resources. That’s where I see the opportunity. And the question is, how do you make those green shoots of innovation more generalized and more the norm? And I do propose in the essay that one way to do that is to strengthen the school-industry linkage so that kids are getting exposed to industry and beginning to explore some of those innovations in real life contexts.

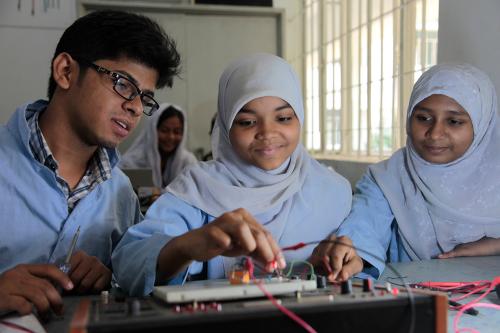

ORDU: Indeed. And one of the things we are finding and of course, you have been at the epicenter of this, is the remarkably few numbers of our young girls and women pursuing careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. How do we address this to attract more young girls and women to STEM?

KAGIA: It is relatively easy if you like in the sense that “to see, is to believe.” When you see women who are successful in science, whether they are in labs, or in hospitals, or in engineering, then you know that if she can do it, I can do it, too. So, just having somebody that you can relate to, who is like you, who is in these fields, so role models become very, very important. And some of the most successful programs in terms of getting women into STEM education have been by just inviting successful women scientists and engineers to interact with these young women.

The second one is providing scholarships and opportunities for women who are smart, who have demonstrated the capability to pursue the courses up to higher levels.

The third one is providing opportunities in work environments either through internships or sort of selective recruitment. You know, these are companies coming in and selecting young, bright women consciously into the workplace.

And of course, I can’t forget this: making sure that you have enough women, female teachers, because in one of the studies that ACET had done, 95% of the teachers are in one school were all men, and there’s no way you are going to even get girls to aspire into science education if they have not seen a single female teacher.

ORDU: I think the issue of role model in studies after study, representation matters, I hear you say, and of course the more we can have female teachers who also act as role models, whether it’s primary or all the way to university is very, very important, especially in STEM education.

Ruth, on education more broadly, you wrote that even before COVID-19 made the situation worse, more than 50% of children in basic education in sub-Saharan Africa were unable to read and understand a simple age-appropriate story. As you know, the World Bank has characterized this situation as “learning poverty.” This is indeed a staggering revelation, 50%, especially as today’s students are tomorrow’s teachers. So, what’s being done, in your view, to address this learning poverty on our continent?

KAGIA: Several things, Aloysius. It is actually a crisis, and it’s a compounded crisis. Part of it is a good reason: is because as education has become more democratized, as more kids have gotten into to school, and access to particularly primary school has become almost universal in many countries, we just dealing with the issue of numbers. And when a teacher has to deal with a hundred kids in a classroom, there’s only so much they can do in terms of individualized focus. So, it’s a good problem to have because at least you have them in the classroom.

The second comment is that just recognizing that being in a classroom or being in a school is not learning. That has been an important recognition because for the longest time the cry was, let’s get them into school. And once they got there, it was almost like they would automatically learn. So, recognizing that schools could become education facades as opposed to learning institutions, that has been important.

And in September last year, the United Nations had for the first time a UN-level discussion on how to actually transform education. It was Transforming Education Summit, that recognized the importance of quality, the importance of inclusion, the importance of equity—issues that we’ve known about but they are not getting sufficient attention as leaders, political leaders and country leaders kind of were addressing competing needs of environment, financing, agriculture, and so on. Education tended to recede into the background in the mistaken assumption that now that we’ve got universal primary education, all is well. So, recognizing that there’s a deficit that needs to be addressed is one.

Three, there has been a lot more focus on learning from each other as an international community. The Global Partnership for Education, for example, that focuses on supporting developing countries, improve their education system, sharing good practices, and supporting them with grant resources is one such effort.

And then finally, the sort of single-minded focus in many ways being spearheaded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to strengthen foundational learning. Because if the foundations are weak, every successive step in education becomes a remedial exercise. So, you find that those in secondary schools are basically making up for what they didn’t get in primary schools, and so on and so forth. So, spending much more effort on getting the foundations right in spite of the constraints of numbers and resources. And it’s much cheaper to do it at the beginning rather than to do a remedial process.

ORDU: Excellent point on foundation, the solid foundation, reminds me of the number of number of children across our continent, the “second chancers” as they call them, who miss out on the opportunities at this foundational stage, or a parent who pays fees has died, or in the case of young girls, they have early pregnancies but they are not by any means less smart than others. And this burgeoning population of second chancers, I’m just wondering, these are all challenges we have on the continent.

So, what are some of the critical lessons that COVID has taught us from your point of view.

KAGIA: That schools are important for protecting our children. We did a study last July where we found the number of girls and boys who had dropped out of school during COVID, the number of girls who went into early marriage during COVID, young boys going to look for work because of COVID. So, the importance of school as protecting, for protecting people, which in essence reinforces what we’ve known for a long time, that the longer you can keep kids in school, particularly girls, the greater the opportunity for them to succeed in life is. So, that was one lesson.

Two, learning doesn’t have to happen just in front of a blackboard with a teacher at the front. Learning can happen anywhere if it is well organized. It was amazing to see the extent to which schools went to make sure kids were learning, involving parents, using radio and TV, using smartphones, in some cases using computers. And then dynamic learning actually did take place when it happened. The challenge was that not everybody had access to those online learning instruments. But the important point is learning can take place anywhere if it is well organized.

And a positive outcome out of that is how you can cooperate as a group of teachers, a group of schools, a group of counties to prepare lessons so that the weaker ones are supported by the stronger ones. That cooperation at the teaching-learning level was more effective during COVID.

And we also learned that if a doctor came into this space we are at today from a hundred years ago, they would not recognize the health system. If a teacher from a hundred years ago came and joined this conversation, they would find things were pretty much the same as they were 100 years ago. So, it was a wakeup call that education, as we are handling it, is a hundred years behind schedule, it needs to sort of be education for the 22nd century as opposed to 18th or 19th century. So because the learners are learning for problems of the future, the environment that they are learning in is the environment of the 22nd century, and yet the methods we are using are the 19th century methods. So a wakeup call to align the reality of teaching and learning to the realities that they are facing.

ORDU: Ruth, conflicts as you know, fragility and insecurity, have imposed huge disruption on the education systems across our continent—next door to you in the Horn of Africa, in the Sahel, in northern Nigeria and elsewhere. What strategies can be deployed, in your view, to ensure that children are able to learn on the move in fragile settings?

KAGIA: It is basically a situation of doing the best with a difficult situation. Because as long as there’s conflict and fragility, the learning environment is going to be suboptimal. So, how do you recognize that? There are several things that could be done. The first is to protect the safety of the children. So, creating safety zones for them, whether it is through a camp or through extra protection by the local administration. But focusing on the safety and security of the children, particularly young girls.

Two, integrating education, teaching, and learning to the broader response to the conflict, because there are not separate activities. Sometimes the communities are moving from place to place. So, making sure that there’s sufficient mobility in the teaching process—not easy, but not impossible.

Three, making sure that the content of teaching focuses on conflict prevention so that conflict does not breed conflict, that these young people grow up recognizing that conflict is not inevitable. And that is easier said than done when you look at some of our neighbors who have been in conflict for several generations. It requires a mindset change for these young people to realize that it’s not inevitable. You can coexist peacefully.

ORDU: As we come to a close, Ruth, looking back at your illustrious career and then looking forward to the future of education on our continent, what would be your top two recommendations for transforming our education systems to assure better outcomes?

KAGIA: I’m always careful not to kind of zero in on only one or two solutions, because if it was a silver bullet, we would have discovered it. Having said so, I would perhaps prioritize political prioritization of education. We saw the difference it made in the ‘60s and ‘70s in Africa when politicians said our primary goal is to eliminate poverty, ignorance, and disease. I recall that after independence, as Zimbabwe’s secondary education expanded by 200%. So, just that political momentum and political focus on the importance of education, not as a political tool, but as a core economic investment to the country… and the subsequent need to allocate sufficient resources, therefore.

The second is to focus much more on quality rather than quantity. So, looking much more at matrices that indicate who is learning and who is not learning. What are the bottlenecks to learning?

And then I know you asked for two, but I’ll add a third one, which is inclusion, because there is no point of educating a few when a whole swathe is being left behind, because then that becomes a seedbed for insecurity at a later point.

[music]

ORDU: Sister Ruth, it’s been a pleasure speaking with you today. Thank you very, very much for making the time for this conversation.

KAGIA: Thank you very much. It’s good to talk to you.

ORDU: I’m Aloysius Uche Ordu, this has been Foresight Africa. To learn more about what you just heard today, you can find this episode online at Brookings dot edu slash Foresight Africa Podcast. The Foresight Africa podcast is brought to you by the Brookings Podcast Network. Send your feedback and questions Podcasts at Brookings dot edu.

My special thanks to the production team, including Fred Dews, producer; Nicole Ntungire and Sakina Djantchiemo, associate producers; and Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer. The show’s art was designed by Shavanthi Mendis based on a concept by the creative firm Blossom.

Additional support for this podcast comes from my colleagues in Brookings Global and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastRisks and opportunities of STEM education in Africa

April 26, 2023

Listen on

Foresight Africa Podcast