This op-ed was originally published by The New York Times.

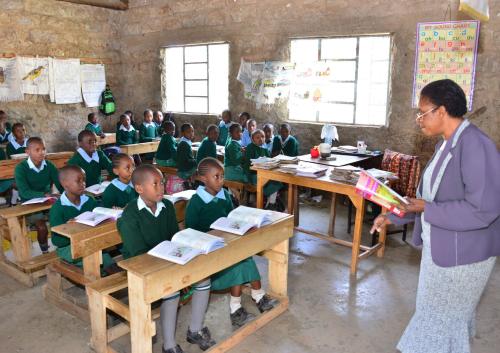

When Michael Kremer looked at the data for a study underway in Kenya in the 1990s, he was taken aback.

Mr. Kremer, a professor at Harvard, expected that the data would show how much better children in western Kenya did in school when they had textbooks. But the preliminary answer was: not at all.

“I was totally shocked by the result,” he said in a recent interview. “Even people who were skeptical that more resources was the way to improve education thought textbooks would help.”

Yet instead of amounting to utter failure, the field experiment helped him earn a share of this year’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, along with the MIT economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, for pioneering the use of field experiments to study which policies best improve the lives of the poor. The Nobel committee noted that “their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics, which is now a flourishing field of research.”

The unexpected result of that particular experiment, conducted with Paul Glewwe, now an economist at the University of Minnesota, and Sylvie Moulin, then at the World Bank, prompted Mr. Kremer to think harder about the schooling system in Kenya. He said he began to realize that one problem was an excessive focus on top students, and he went on to design and test other measures that would help a broader range of people.

The field experiments conducted by Mr. Kremer, Mr. Banerjee and Ms. Duflo—which they sometimes work on together—resemble the drug trials that pharmaceutical companies use to test new medicines. The economists’ experiments typically compare participants in anti-poverty programs with peers without access to the programs. The researchers choose program participants by lottery, or the arbitrary order in which a program is offered to people.

For example, in the study on textbooks, a nonprofit rolled out a free textbooks program gradually over several years. Some lucky schools received textbooks one to four years before others. To assess the benefits of textbooks, the researchers compared the test scores of students in the lucky schools with those of peers in the schools still in line to get textbooks.

Using field experiments to study poverty this way has attracted both praise, as evidenced by the Nobel award, and criticism on technical and broader grounds. Angus Deaton, himself a Nobel laureate, has cautioned that field experiments should be designed carefully to shed light on why a method worked and where else it might work. Otherwise, he has said, such experiments might not advance knowledge much.

I can attest to the new Nobel winners’ role in reshaping the field of development economics. They certainly influenced me. All three were my teachers when I was in graduate school at Harvard starting in 1999. In those days the field was small enough that they taught a combined class for Harvard and MIT students, and Mr. Kremer and Mr. Banerjee were among my advisers.

I have run randomized experiments in India, Uganda and elsewhere on topics such as how to improve child nutrition, protect forests, and reduce gender discrimination. Some of the interventions I have tested had beneficial effects, and others did not.

Learning early that a program has limited benefits is useful for the organization running it and the donors funding it. They can redirect their time and money elsewhere, or try to change the program to make it more effective.

But Mr. Kremer’s Kenya textbook study illustrates another value of discovering that a program falls short of its promise. This type of so-called null result, where the impacts of an intervention are indistinguishable from zero, can lead us to think differently and more creatively.

When Mr. Kremer and his colleagues looked at their data in more detail, they saw that textbooks did help the students whose test scores were very strong before the experiment began. That finding got the researchers thinking harder about what features of the Kenyan education system led to this pattern, he said.

The deep problem with the schooling system, Mr. Kremer believed, was that it was geared toward the top students. He speculated that this might have been a vestige of the colonial era, when access to education was mostly limited to children from relatively privileged families. Today, education is available to children from a much wider range of family backgrounds, but the curriculum has not been adapted enough, he said.

An obvious change would be to rewrite the textbooks so they are at the right level for the average student. However, because of the big variations in student preparation, that redesigned textbook would still be too hard for some people and too easy for others.

What was needed was instruction tailored to the needs of students at different levels. While Mr. Kremer was puzzling over his results on textbooks, Mr. Banerjee and Ms. Duflo began a field experiment in India to evaluate a program aimed at helping struggling students catch up. In Indian schools, as in Kenya, such students were often left to flounder. The researchers collaborated with an Indian nonprofit that placed extra teachers in schools to help the weaker students master basic literacy and numeracy skills.

Ms. Duflo said, in an interview, that it was largely a coincidence that her first foray was so thematically aligned with Mr. Kremer’s results. She and Mr. Banerjee were keen to collaborate with the nonprofit, Pratham, which happened to be pursuing remedial instruction.

But Mr. Kremer’s surprising results deeply influenced her, she said. She remembers him puzzling over them when he taught her as a graduate student at MIT.

“The fact that he didn’t find what he expected—it’s not so important that it was a null result as much as that it was unexpected—it made me much more interested in randomized trials than I would have been if I thought it was just a way of confirming intuitions you already have,” Ms. Duflo said.

Mr. Banerjee and Ms. Duflo found that the remedial instruction in India had large benefits for the weaker students, and further studies also showed that remedial education seemed to work while adding other resources did not.

Ms. Duflo and Mr. Kremer then worked together, along with Pascaline Dupas, now at Stanford University, on another educational program in Kenya directed toward the entire spectrum of students. They studied what happens when you place students into classes based on their academic preparation.

With less variance in students’ level, teachers could aim their instruction more precisely. The researchers found that the program increased student achievement for the entire range of students.

The negative finding about textbooks was important in the development of Mr. Kremer’s career. “I’m happier when I find that something works,” he said. “But I’m not in despair if I don’t—the key thing is listen and learn from it.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edWhen a disappointment helped lead to a Nobel Prize

December 30, 2019