Before resigning from his post due to allegations of illicit enrichment, Brazil’s disgraced ex-Chief of Staff to the President Antonio Palocci, who was considered one of the most influential officials in President Dilma Rousseff’s Worker’s Party (PT), dominated government. It’s not the first time that Palocci had resigned during a PT administration; his previous resignation stemmed from a scandal during the Lula administration when Palocci was involved in an illegal violation of the fiscal secrecy of the housekeeper, Francelino dos Santos Costa, who named him as a habitual visitor to a prostitution house in Brasilia. Nonetheless, that sex scandal was not an impediment for Palocci’s accession to the Casa Civil, since he had the support of former president Lula, who sternly lobbied for his appointment.

During the most recent accusations, the chief prosecutor decided not to open a formal investigation of Palocci’s activities and shelved the inquiry demanded by three opposition parties. However, unlike their blind support during the Lula administration, Palocci’s own political party also abandoned him during the aftermath of the scandal. For example, when PT senator Marta Suplicy tried to set a motion in the Senate in support of Palocci, she could not get even a single PT senator to sign her petition.

PT’s condemnation of Palocci showcases the contradictory beliefs in what they deem to be corruption. In the past, the PT had absolved Palocci and other members of the party from any responsibility in other cases if activities were undertaken in alignment with the party’s interests. Nevertheless, they deemed Palocci’s alleged personal choices to run counter to their agenda.

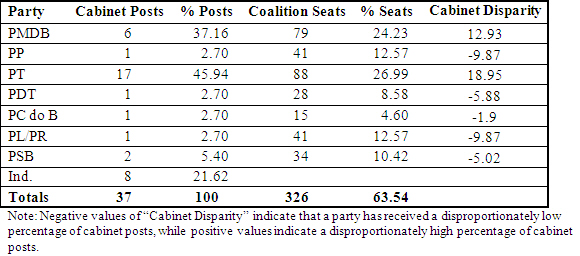

Table 1 shows the composition of Rousseff’s first cabinet, including the number of ministerial positions allocated to each party, the number of seats held by each party in the coalition Congress, and the cabinet disparity (i.e. the difference between percentages of cabinet posts held by the party and percentage of house seats held by the party). The chart demonstrates that when constructing her coalition cabinet, Rousseff’s appointments were unbalanced, heterogeneous, over-sized and over-concentrated. She preferred to satisfy the internal factions within the PT and members of her principal coalition partner, the Brazilian Democratic Party (PMDB). The only parties with positive cabinet disparities are the PT and PMDB with 18.95 and 12.93 respectively. In other words, these two parties received a disproportionately high percentage of cabinet posts, which do not reflect their proportional weight in Congress, 88 seats (26.99 percent) and 79 seats (24.23 percent) respectively. Still, the coalition formateur, the PT, holds an oversized number of cabinet positions.

Table 1: Rousseff’s First Cabinet, Coalition Seats, and Cabinet Disparity

The lack of support Pallocci received from coalition members after the money laundering allegations can be interpreted as the price Rousseff paid for allocating a disproportionate cabinet. A sustainable majority coalition serves not only to approve president’s agenda in Congress, but also to veto unwelcome legislation or block opposition initiatives capable of embarrassing the government. An unsatisfied coalition will be less motivated to bear the political costs of supporting government’s interests in moments of crises like Palocci’s case.

After Palocci’s departure, Rousseff seems to have wasted a window of opportunity; she could have reshuffled her cabinet to reflect a more appropriate allocation of cabinet positions to other coalition partners that have so far been under-rewarded. Instead, Rousseff attempted to assert her leadership by appointing junior PT Senator Gleisi Hoffmann the new chief of staff and Idelli Salvati, a former PT senator, as the new head of the Secretariat of Institutional Relations. Both politicians are renowned for having the same personal traits as Rousseff–a strong character, and technical and hierarchical—and are expected to play the same role that Rousseff once played for Lula.

Rousseff’s strategy behind the Palocci resignation does leave some food for thought. In an attempt to assert her authority, Rousseff disregarded an essential unwritten rule of proportional and ideologically homogeneous coalition government and increased tensions with governing coalition partners. Rousseff’s unilateral move represents a very risky gamble. She asserted her stern leadership style in a country where politics have always been characterized by the fine art of compromise. Surprisingly, it seems that her bet to appoint more PT members to the cabinet has contributed to the boosting the standing of her personal image among Brazilian voters. According to polls, 7 percent consider Rousseff’s performance “terrible”, 34 percent consider her performance fair, 47 percent consider it good and 12 percent declined to express an opinion.

It remains to be seen how the Brazilian political machine reacts to Rousseff’s bold actions. After all, during successive administrations it is this mechanism that has historically been the enabling force behind “smoother” governance in Brazil.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edThe Price of a Disproportional Cabinet: The <em>Paloccigate</em> in Brazil

June 28, 2011