Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

Opening the political sphere, empowering the legislative branch, promoting and protecting civil and political rights would go a long way towards diminishing popular dissatisfaction with Morocco’s political dynamics, says Yasmina Abouzzohour. This piece was originally published by the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis.

The Moroccan police on December 26, 2019 arrested journalist Omar Radi after charging him. Radi spent six days before being released on bail. His trial is set for March 5, 2020. His crime according to the authorities? Tweeting six months ago in criticism of a judge involved in the trials of Rif activists. This official reason is confusing given the timing of Radi’s arrest. In fact, it is possible that Radi’s arrest was motivated, not by his supposedly “insulting a magistrate” six months prior, but by an interview he gave on an Algerian radio channel on December 23 discussing the Moroccan regime’s expropriation of tribal lands.

A pattern of judicial repression

The regime has displayed a pattern of repressing activists through judicial proceedings, sometimes under false pretexts. Indeed, famous activists perceived by the regime as dissidents- such as Radi, the journalist Hajar Raissouni, and the rapper Gnawi- are taken to court over unrelated issues, such as a supposed abortion in Raissouni’s case or a video that allegedly incited violence against the police in Gnawi’s case.

In fact, Omar Radi was not the only Moroccan to face prosecution over freedom of expression on December 26. That same day, YouTuber Mohammed Sekkaki (known as Moul Lcasquetta) was sentenced to four years in prison and a 40,000-dirham fine (close to four thousand dollars) for accusations of “insulting the king” in several YouTube videos. In a similar case, Mohamed Ben Bouddouh (known as Moul Lhanout) was arrested earlier in December in Tifelt for criticizing the king on social media. His whereabouts are currently unknown.

In the same week of Radi’s arrest and Sekkaki’s sentencing, Abdelali Bahmad– an unemployed youth and former member of the National Union of Moroccan Students- stood trial on December 23 for “insulting the country’s flag and symbols” and “violating [its] territorial integrity” on social media. Bahmad, who had participated in several protests in Al Hoceima and Jerada, was arrested in the past due to his political activism.

Activists and journalists who criticized the regime have faced increased repression since the 2011 uprisings, but they are not the only ones targeted by this sort of crackdown. Most notably, the Rif protests– catalyzed by Mohcine Fikri’s death and triggered by economic hardship, social inequality, and government corruption– were met with brusquerepression. Protest organizers were handed down 20-year prison sentences, and several mid-level Rif protesters have sought asylum in Europe after receiving summons to appear. While a royal pardon suspended many of the Rif sentences, high-profile activists remain in prison.

The regime’s judicial repression of critical voices targets not only activists but non-politicized young people as well. For instance, an eighteen-year-old high school student in Meknes was sentenced on December 19 to three years in prison for a Facebook post in which he used the lyrics of the controversial song “Aach Achaab” (Long Live the People). Gnawi, one of the rappers who wrote and performed the song, is himself currently serving a one-year jail sentence supposedly for insulting the police in a video released in October. However, his lawyer maintains that the legal proceedings targeting his client were motivated by the controversial song. Another eighteen-year-old high school student was arrested near Laayoune on December 29, 2019 for posting a rap song on YouTube criticizing the kingdom’s socioeconomic situation and qualifying the regime as a “dictatorship.” He was sentenced to four years in prison on December 31, 2019.

The practice of silencing dissident voices through legal proceedings is not a recent phenomenon. On October 17, 2018, entrepreneur Soufiane Al Nguad was sentenced to two years in prison and a 20,000-dirham fine (around two thousand dollars) for “inciting public violence,” “insulting the country’s flag and symbols,” and “propagation of hate.” Al Nguad had published a Facebook post calling people to protest after the Moroccan navy had shot a migrant speedboat on September 25, 2018, leading to the death of 20-year-old Hayat Belkacem.

The previous year, on August 4, blogger Mohammed Taghra was arrested in Ouled Teima and was sentenced to 10 months in prison for “criminal defamation.” Taghra had published a video report on police corruption (in which he interviewed local citizens and asked about their firsthand experience on the topic). His videographer, Badreddine Sekouate, received a four-month sentence. Taghra’s sentence was later reduced to four months while Sekouate’s was suspended.

The myth of Moroccan exceptionalism

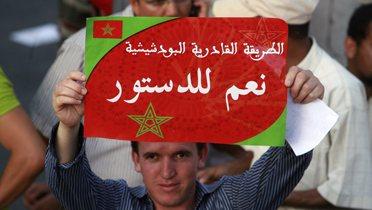

The Moroccan regime’s pattern of judicial repression may come as a surprise to outside observers who had applauded the regime’s reaction to the 2011 uprisings and what some termed “Moroccan exceptionalism.” The latter argues that the kingdom successfully contained the uprising by behaving exceptionally, through pre-emptive reforms , and due to inherent legitimacy (tribal, religious, or historical). While Morocco was integrated with the other Arab monarchies in the “monarchy-republic divide” coverage of the uprisings, by far the most popular angle used to explain the Moroccan regime’s survival is one related to its so-called reformist behavior. This argument overlooks the reported violence against February 20 activists and the wider protest movement, and it focuses on positive changes made to the constitutional text in 2011.

Close to ten years after the 2011 uprisings, however, this argument has been disproved by (1) the lack of genuine change within the political system, as well as (2) the authorities’ repeated judicial harassment of activists, (3) the regime’s unwavering repression of protesters in Al Hoceima, Jerada, and elsewhere, and (4) police forces’ brutal shutdown of scattered protests across urban centers.

Outlook: So long, Human Rights!

Omar Radi may receive a prison sentence – in which case he may be pardoned or the charges against him may be dropped due to the popular backlash triggered by the unfair accusations made against him. However, beyond this singular case, the degradation of human rights in Morocco is concerning.

Unbridled by domestic or international human rights organizations, the Moroccan regime will have little incentive to stop repressing protestors and activists as the socioeconomic crisis that inspired recent popular unrest persists. Indeed, according to the World Bank, a quarter of Moroccans are poor or at risk of poverty, and the gap between the highest and lowest socioeconomic classes is wide. Morocco’s Gini Coefficient (i.e., inequality index) is 40.9%, meaning it has not improved since 1999. This is the highest rate in North Africa – excluding Libya which is in the throes of civil war. Morocco also ranks lower than its neighbors in the UNDP Human Development Index, especially in terms of healthcare, education, and access to electricity and clean water. Furthermore, Morocco struggles with high youth unemployment rates, which reached 22% nationally and 43% in urban areas in 2017.

These persistent socioeconomic woes will motivate further unrest, which creates a threat to the regime. This threat, combined with an opaque executive and low public trust in government and political parties will probably lead to unorganized repression. However, increased repression is unlikely to put an end to protests which are bound to multiply as social inequality persists. Any further crackdown will only exacerbate the population’s underlying disillusionment.

A smart move on the regime’s part, as it continues to struggle with finding a development plan that effectively targets territorial and demographic inequalities, would be to genuinely liberalize. Opening the political sphere, empowering the legislative branch, promoting and protecting civil and political rights would go a long way towards diminishing popular dissatisfaction with Morocco’s political dynamics. However, the regime is unlikely to take this route given its recent crackdown on protesters and activists. Rather, as the socioeconomic situation incites further discontent, the regime will likely continue to target activists and protesters through legal proceedings and increased surveillance.

After all, it is ten years after the Arab Spring, and the regional chaos that once incited the Moroccan regime to promise genuine change is long gone. In 2020, the regime will likely see little reason to introduce reforms that might open the political sphere and potentially reduce its own powers. In fact, the regime will more likely double down on its pattern of repression to maintain the status quo at the expense of human rights.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edMorocco’s sharp turn toward repression

Wednesday, January 8, 2020