Most governments around the world would declare their adherence to the principles of fairness and equity. But how should principles inform practical policies for allocating public spending? That question was at the heart of a two-day seminar held last week in Naivasha, Kenya.

Organised jointly by the Office of the Prime Minister, the Ministry of State for Development of Northern Kenya and other Arid lands, and the Commission on Revenue Allocation (CRA), and facilitated by the United Nation’s Millennium Campaign, the Naivasha seminar, Financing for a Fairer, Prosperous Kenya, addressed an ongoing public debate prompted by the adoption of a new constitution in 2010. The outcome of that debate will have profound consequences for poverty reduction in Kenya – and the issues raised have a resonance far beyond Kenya’s borders.

Adopted in 2010, the Kenyan constitution is a remarkable document. It shifts the locus of political authority away from what has been a highly centralized state toward 47 devolved counties. It enshrines far-reaching provisions on social and economic rights, including a new bill of rights. And it includes an injunction requiring all layers of government to apply the principle of “equitable sharing” to public spending, with an emphasis on “the need for affirmative action in respect of disadvantaged groups and areas.”

There are compelling grounds for policymakers in Kenya to prioritize greater equity. Wealth disparities are marked. The Gini co-efficient for wealth distribution is 0.44, which is higher than in neighboring countries like Ethiopia and Tanzania. Economic growth has been skewed toward urban centers and a narrow band of commercial farming areas, with the World Bank estimating that 80 percent of economic activity is generated in just half of the new counties.

While Kenya’s social indicators have been improving, national averages obscure deep sub-national fault-lines. Child mortality rates among the poorest 20 percent of households are twice as high as those among the richest 20 percent. Young adults from the poorest quintile have five years less schooling than those from the wealthiest households.

Intersecting with these wealth-based disparities are some of Africa’s starkest horizontal disparities. In a report prepared at the request of the Ministry for Northern Kenya and presented at the Naivasha seminar, the Brookings Center for Universal Education looked at social indicators for 12 of the Arid and Semi-Arid Land (ASAL) counties. Among the key findings:

- Poverty incidence in counties such as Marsabit, Wajir, Mandera and Turkana exceeds 80 percent – double the national average. Apart from being more pervasive, poverty is also far deeper.

- The 12 counties account for just over 20 percent of Kenya’s primary school age population, but almost half of the out-of-school population. They account for 9 of the bottom 10 counties in the national league table for enrollment.

- Gender gaps in education are among the widest in Kenya both in terms of access, progression through schools and test scores. In some of the ASAL counties, there are twice as many boys as girls in secondary school. Those (very few) girls who make it through the education system to take the secondary school exam are half as likely as boys to achieve the grade required to secure state funding for higher education.

- Health service coverage is limited. Just 5-6 percent of births reported in Wajir and Turkana are attended by skilled health workers, compared to a national average figure of over 30 percent.

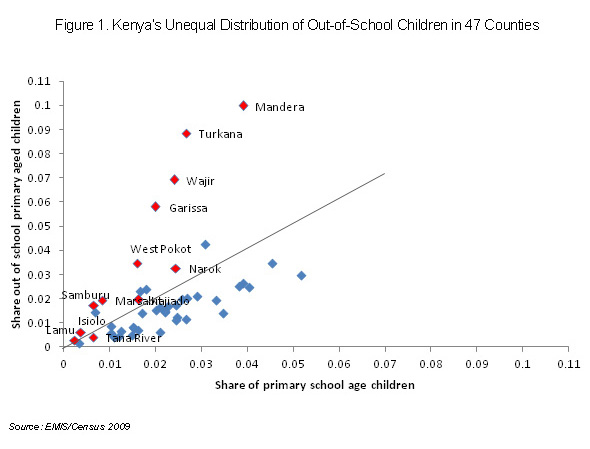

Some current public spending practices reinforce, rather than mitigate, these disparities. Consider the case of primary education, as illustrated by two simple figures. Figure I provides a snapshot of the share of each of Kenya’s counties in the total primary school age population, and the share of that population which is out of school. The 12 ASAL counties covered in the Brookings report are demarked by red dots. All but one is to the left of the “line of equivalence” – the point at which the county’s out-of-school share is equivalent to its share of the school population. For example, Turkana accounts for just over 2 percent of the school age population, but 9 percent of the out-of-school population. This is a stark illustration of the unequal life-chances facing children n many of the ASAL counties.

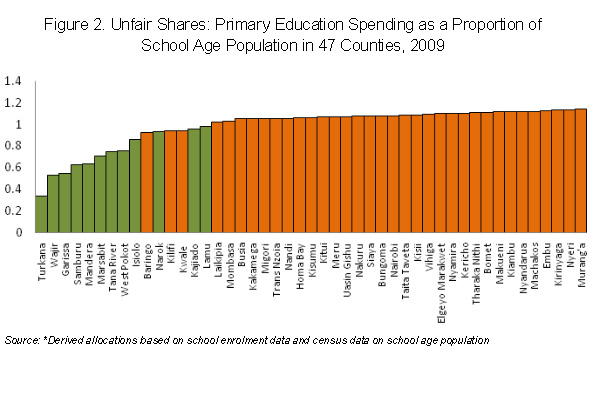

Given the level of education disadvantage facing children in the ASAL counties, an equitable system of public spending might be expected to transfer more per pupil than to other counties. In the case of Kenya, the inverse principle applies. Figure 2 measures the ratio of public spending received by each county against the county’s share of school-age children (equivalence is demarked by a ratio of 1). The ASAL counties (green columns) receive less than they would if the budget were allocated as an equivalent transfer for each child – in some cases, much less. Thus, budget transfers to Turkana are less than half of the level that would take place on the basis of equivalent transfers per child. The reason for the disparity: transfers are determined by the number of children in school, penalizing those counties with low school participation rates. Put differently, those with the greatest need get the smallest slice of the budget cake.

The new constitution marks a bold attempt to set Kenya on a course toward a more equal society. Prompted in part by the wave of violence that followed the 2008 election, its provisions reflect a broad public concern that the deep social fault lines running through Kenyan society are a source not just of social injustice, but of political instability and economic inefficiency. The CRA has been charged with translating constitutional principles in favor of greater equity into concrete policies for allocating government revenue.

That is no easy task. The CRA’s remit extends not just to the 15 percent of government revenue that will be allocated directly to the new counties, and to the design of a new Equalization Fund (0.5 percent of revenue), but to all public spending. Reaching a broad consensus in favor of “equitable sharing” is one thing. It is quite another successfully to navigate the political process through which public spending is allocated across counties, social groups and sectors.

The Naivasha conference explored a range of international approaches to equity in public finance. One particularly instructive case-study, presented by Pinaki Chakraborty of the National Institute for Public Finance and Policy in New Delhi, focused on India. This country has a highly devolved system of public finance, with around one-third of federal government revenue allocated to states. The allocation is governed by a horizontal distribution formula which takes into account the fiscal capacity of each state (their ability to raise revenue), population, land area and other factors. Broadly, the formula aims at narrowing fiscal inequality between richer and poor states, and at equalizing capacity to deliver basic services.

Wider experiences are also relevant to the debate in Kenya. In South Africa, public financing has sought to narrow the extreme disparities associated with the legacy of apartheid, in part through a Provincial Equitable Share formula that allocates additional resources to devolved governments in regions with large populations facing disadvantages in health and education. Fiscal devolution in Ethiopia is governed through a formula that measures fiscal capacity against the estimated costs of achieving specific policy targets, in some cases geared toward the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

While international experience is instructive Kenya clearly needs to chart its own course towards ‘equitable sharing’. The country is on a distinctive pathway. While political authority is being devolved to the counties, revenue mobilization will remain highly centralized (a marked contrast to the situation in large federal countries like India and Brazil). Some major sectors will not be devolved, including education. And while there has been an extensive debate over how to weight different types of inequality, the data available is often dated, unreliable and contested.

The CRA has made some initial proposals. In a framework submitted to parliament in May, it outline a formula for devolved financing that would allocate 60 percent of the budget on the basis of population size, 20 percent as an “equal share” to every county, 12 percent in the form of an equal payment for every person living below the poverty line, with residual transfers linked to land area and fiscal performance. Intended to generate a public debate, the formula is now under revision.

Proposals set out in a forthcoming Brookings Center for Universal Education paper advocate five core reforms to the current framework:

- Attach more weight to equity: The 2010 constitution is unequivocal in demanding that public spending plays a greater role in mitigating disadvantage. While income poverty is a partial indicator of disadvantage, it should carry a weighting of 30-50 percent in the devolved financing formula. One of the weaknesses of the CRA’s approach to date has been in the undue weight attached to population and equal per capita transfers. Providing an equal payment for people and counties in very unequal positions is not compatible with the constitution’s equitable sharing provisions.

- Focus on the poverty gap: The current formula envisages equal transfers to each poor person, irrespective of their distance from the poverty line. In the Brookings paper, we advocate for an approach that weights each county’s share in the national poverty gap – and approach that would capture the depth of poverty and, by extension, the costs of eliminating poverty.

- Look beyond devolved financing: Much of the debate in Kenya has focused on the devolved budgets, to the exclusion of the 85 percent of public spending that will remain under the control of central government.

- Identify equitable financing approaches for each sector, starting with education. As the major non-devolved basic service budget, education is a test case. Kenya urgently needs to move away from the current “equal finance for each pupil” model and toward “an equal chance for every child” approach. The Brookings paper explores a number of options and calls for an approach that would allocate spending through the following formula; 50 percent for children in school, 20 percent for children out of school, 20 percent on the basis of the county share in the national poverty gap, with residual transfers linked to gender equity and a special fund for the most disadvantaged ASAL counties.

- Develop a cost-based citizenship entitlement framework: The 2010 constitution enshrines a number of citizenship rights to basic services. If these rights and entitlements are to be translated into real entitlements, government needs to establish the costs of provision and to allocate resources against these costs.

The debate on public spending prompted by the new constitution provides Kenya with a real opportunity to accelerate human development. Current levels of inequality are a source of social injustice, political instability and economic inefficiency, with disparities in opportunity acting as a drag on growth. As the recent history of Brazil has demonstrated, strategies that are good for equity and the development of more inclusive societies can also be good for growth. The converse also holds true.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the fiscal framework for devolved financing in Kenya. Much will depend on political leadership. The CRA is staffed by highly competent professionals. Ultimately, though, it is a technical advisory body set up to recommend on options. So far, political leaders have been content to take a back seat. They have steadfastly avoided engaging the public in a wider debate on the case for greater equity, preferring to delegate responsibility to the CRA without establishing clear guidelines.

If Kenya is to translate the bold new principles of the constitution into policies that expand opportunities for the country’s most disadvantage people and marginalized counties, political leaders will need to abandon the back seat and provide real leadership. The wider challenge for Kenya’s elite is to recognize that the real threat to the country’s future is not from an imagined trade-off between economic growth and equity, but from a continued indifference to the inequalities that are destroying so much human potential, hampering productivity and fuelling social division.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edFinancing for a Fairer, More Prosperous Kenya

July 11, 2012