What really defines austerity? In the context of a stagnating economy or recession as seen in Greece, austerity is: increasing taxes on productive economic sectors and households, slashing wages and pensions, and reducing public expenditures. This is Economics 101.

It is widely known and accepted that Greece desperately needs growth, and after five years of severe economic contraction, almost everyone agrees that any measures should not be of a pro-cyclical direction. Instead, efforts should be made—bearing in mind the period of 2 percent deflation for a consecutive 2-year period—with the target to mobilize existing resources, taking advantage of idle resources to strengthen the domestic growth potential.

The European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund, sometimes referred to as “the troika,” have roughly proposed a VAT equalization across all of Greece’s regions and islands, but if an agreement could be reached on taxing only the country’s prosperous islands with 23 percent, the rest of them could continue with the current, lower VAT. This would have a negligible impact both on tourism revenues as well as general spending in the economy, so the negative impact on GDP would be negligible.

As for slashing wages, the troika is proposing the implementation of a uniform pay structure in the public sector. Such a pay structure would be a pillar of social justice and ex ante performance evaluation, and would automatically increase wages of the competent and skilled and decrease wages of the less qualified. It will also improve incentives, thus making for more efficient distribution of resources. Overall the impact on spending and GDP will again be negligible.

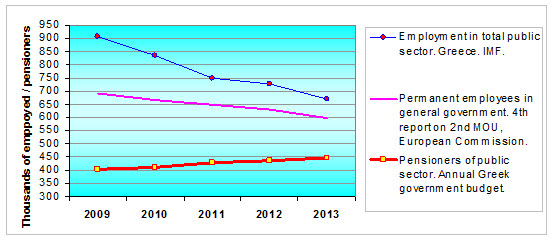

What about pensions? The troika are asking for a 2 percent of GDP (for 2015-2016) decrease of state contributions, which would see Greece approach the average European levels. But, as far as I know, the troika says nothing regarding where to spend alternatively this 2 percent. If this 2 percent of GDP is extracted from the economy, it will certainly have a contractionary effect; yet as proposed, this is not certain. One thing is sure. Parametric changes should take place for the sake of the youth, the hard working, already overtaxed people, and above all, for the future of Greece. The pension of a 55-year-old retired senior police officer is around 1,650 euros per month. A lecturer working in a university is earning around 1,200 euros (net, after tax and social security contributions). As you can see for yourself in figure 1, there are currently less than 700,000 public servants working in the total public sector and a little less than 500,000 public sector pensioners. There is no way for the country to prosper with a situation like that.

Figure 1. Pensions in the Greek public sector

Regarding Greece’s primary balance, both the government and the “institutions” (troika) are very close to agreement on the “+1 percent” for 2015. This is a serious rollback from the +3 percent agreed to with the previous government, and the financial gap is supposed to be covered both with new taxation and a new loan, possibly from the European Stability Mechanism. This a victory of the government over the troika as a 1 percent surplus will possibly not have a serious contractionary result on domestic spending and GDP. But if the gap is financed with extra taxes, as the Syriza government is actually planning to do, raising the 45 percent rate on incomes over 50,000 euros an extra 4 percent (and 8 percent for even higher incomes of above 100,000 euros!), the impact on spending and GDP will be substantial and certainly will have a contractionary effect on the economy.

More than 200,000 people have left Greece over the last 4 years; raising taxes on the people that already exclusively bear the heavy tax burden of the country will simply boost emigration, lead to less production, less tax revenues, and less social security contributions. Such a plan also will push productive sectors of the economy either outside the country or to the fringe of black market. This too is elementary economics.

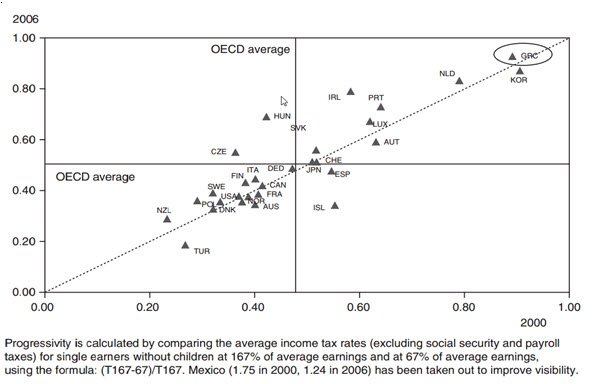

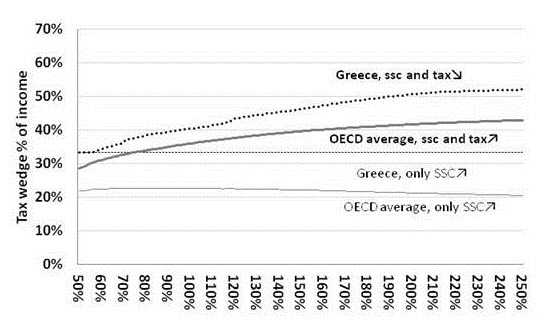

A final point here: according to declare incomes, Greece had (figure 2) and still has (figure 3) the most progressive tax system in the OECD, contrary to what is commonly believed. In addition, also contrary to common perceptions, there has been a huge improvement in the means and the functions of the Greek tax authorities due to the work that has been done both by the Greek governments and the troika, and tax evasion has significantly declined. So, beware of clichés about wealthy Greeks not paying taxes and remember to always look at the data.

Figure 2. Taxation progressivity in the OECD

Source: OECD

Figure 3. Tax wedge in Greece, 2014

Income as percent of national average income.

Source: OECD. Note: One-income family with two children.

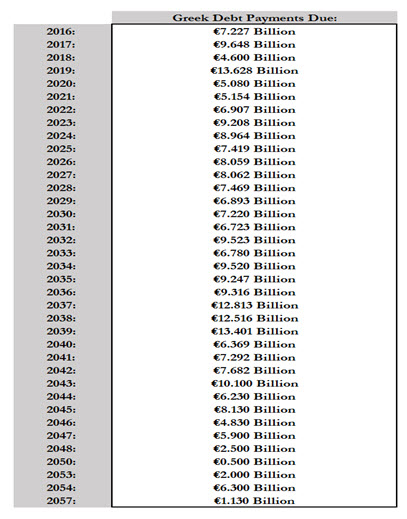

The discussions have now moved again to the level of debt, as it is reported that the government is asking the troika to officially declare along with a potential agreement that they will soon institute a “haircut” or extend the bilateral and European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) loans. Many times now finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has declared that Greece needs a haircut and that sky-high debt makes the economy toxic. This is again a popular view, albeit one often adopted uncritically by many analysts and academics. Figure 4 shows that, since 2016, annual tranches to be paid by Greece are very low by international standards and an average bond’s maturity fluctuates at around 18 years. Average interest rates are also projected to be extremely low, at 2.4 percent (figure 5). The troika also could easily extend the EFSF and bilateral European loans for 10 years without bearing any cost to the European taxpayers, and give Greece another 30 billion euro bonus breath for the coming years.

Figure 4. Projected Greek debt payments

Source: Stratfor, 2015.

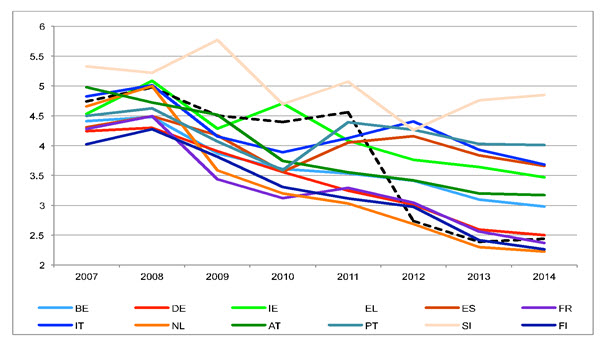

Figure 5. Effective interest rates on public debt, %

Source: AMECO data, T. Pelagidis and M. Mitsopoulos, Who’s to Blame for Greece?, London, MacMillan/Palgrave November 2015, forthcoming.

In conclusion, with the troika plan Greece is not being asked to slash wages; and, while pensions should be restructured, we still need to know what will happen with the amount proposed savings so as not to have a contractionary effect on the economy. In contrast, further huge tax increases proposed by the government both to corporations and households of an annual income above 30,000 euros is an austerity measure that will hurt growth, employment, and incomes in the economy. The target should be to help the economy restore confidence, and create new jobs. For these matters, both parties have to do a lot more.

Read more from Theodore Pelagidis on the Greek economy in his Brookings book “Greece: From Exit to Recovery?”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Comparing proposals for the Greek economy: The Troika vs. the Syriza government

June 18, 2015