In 2002, when President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), few would have predicted the law would last. Yet persist it did, and the controversial legislation remains on the books more than a decade later. Now that Democrats and Republicans have recently started its reauthorization process, it is time to examine one particular aspect, special education, that raises several different challenges.

Assessment of students with disabilities is perhaps the thorniest issue in education policy. For decades students with disabilities were not assessed or educated along with their peers. Schools, like all organizations, value what they can measure. The education system did not value students with disabilities because their success or failure was not counted.

That changed with the passage of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). It mandated that students with disabilities participate in state assessments. States argued it was unfair for students with severe cognitive disabilities to take a general test because they were unable to achieve proficiency. Disability advocates were right to include all students in assessments and states were correct that some students would struggle to succeed in the new system.

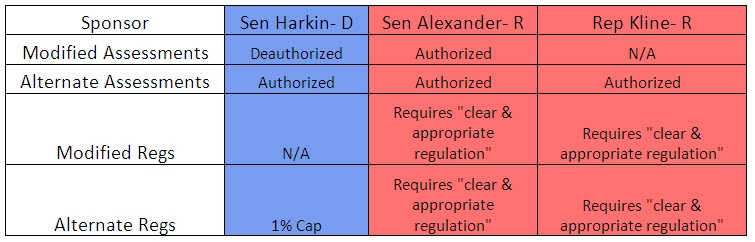

To address this issue the Education Department issued regulations allowing states to alter assessments for some students with disabilities. Students who received support services but were unlikely to achieve proficiency on the general test could take a modified assessment covering the same content with easier questions. Students with the most severe cognitive disabilities could take an alternate assessment that covered less content and included less challenging questions. The Department also placed caps on the number of students whose scores could count as proficient on modified (2%) and alternate (1%) assessments. The intent was to ensure all students were counted and also to recognize that students with severe disabilities may not reach grade level proficiency.

Despite these changes, the core policy conflict remains. Some schools inappropriately administer modified assessments to students who could achieve proficiency on the general test to artificially raise scores. However, many of those students rightly take an alternate assessment. The assessment of students with disabilities will remain difficult until researchers gain a better understanding of all cognitive disorders. Until then policymakers will have to balance setting high expectations without overburdening schools and students.

Congress should deauthorize modified assessments and reauthorize alternate assessments but without a cap. Research indicates that very few students have the most severe cognitive disabilities. Due to natural variation, there are undoubtedly some schools where the percentage of students with severe disabilities is greater than 1%. In some areas, for example, industrial accidents or high concentrations of toxins can lead to spikes in disability rates. In those cases, a 1% cap places a harsh burden on teachers and students. Until cognitive science and assessment technology has improved substantially students with severe cognitive disabilities should not take the general assessment.

Lawmakers should adopt an assessment system that uses computerized adaptive tests (CAT). Adaptive assessments create a custom test for each student based on their answers to test questions. Using an adaptive test vitiates the need for an alternate assessment because it administers test items at the student’s real grade level. This removes the need to administer a fixed form test with simpler questions. Adaptive testing also has built in presentation and response accommodations. This flexibility allows all students to take the same exam.

Congress should also empower parents to make choices about the assessment of their child. Currently parents have few options after a school decides whether the general or alternate assessment is appropriate. Ideally the school would make the initial judgment about administering an alternate assessment. Parents could then choose if they wanted their student to participate in the general assessment. Empowering parents and students has served as a successful strategy in the past. IDEA gave parents the right to sue if students didn’t receive the services they needed. Parents often have greater knowledge of their child’s capacity than educators or researchers.

The politics of No Child Left Behind will probably not allow for a full reauthorization. However, the politics of special education are unique. Disability impacts all Americans regardless of class, race, or party registration. Democrats and Republicans have shown a willingness to look past partisan blinders on this issue in the past. Congress should honor that legacy by demonstrating we value the learning of all students.

2013 No Child Left Behind Reauthorization Proposals on Assessment Special Education Assessment

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Special Education: The Forgotten Issue in No Child Left Behind Reform

June 18, 2013