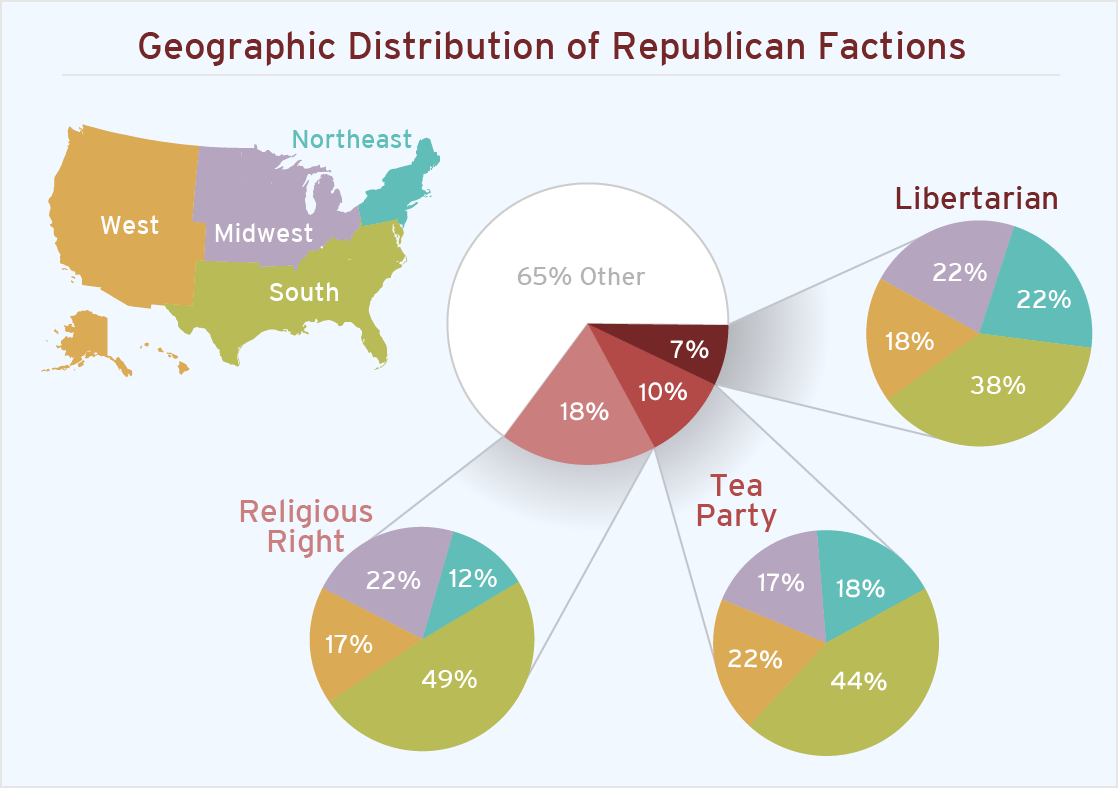

Editor’s Note: This post was updated on January 7, 2014 to include a graphic showing the Geographic Distribution of Republican Factions.

Would a stronger appeal to libertarian values help the Republican Party win elections? This was one of the central questions raised during a discussion of the Public Religion Research Institute’s (PRRI’s) American Values Survey, “In Search of Libertarians in America,” launched at the Brookings Institution on October 29th, 2013.

Libertarianism has become a major part of the political conversation in the United States, thanks in large part to the high profile presidential candidacy of Ron Paul, the visibility of his son Rand in the United States Senate, and Vice-Presidential candidate Paul Ryan’s well-known admiration of Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged.” And the tenets of libertarianism square with the attitudes of an American public dissatisfied with government performance, apprehensive about government’s intrusiveness into private life, and disillusioned with U.S. involvement overseas. Libertarianism is also distinct from the social conservatism that has handicapped the Republican Party in many recent elections among women and young people.

Within this context, libertarians seem likely to exercise greater sway on the Republican Party than at any other point in the recent past. But a closer look at public attitudes points to many factors that will limit the ability of libertarians to command greater influence within the GOP caucus.

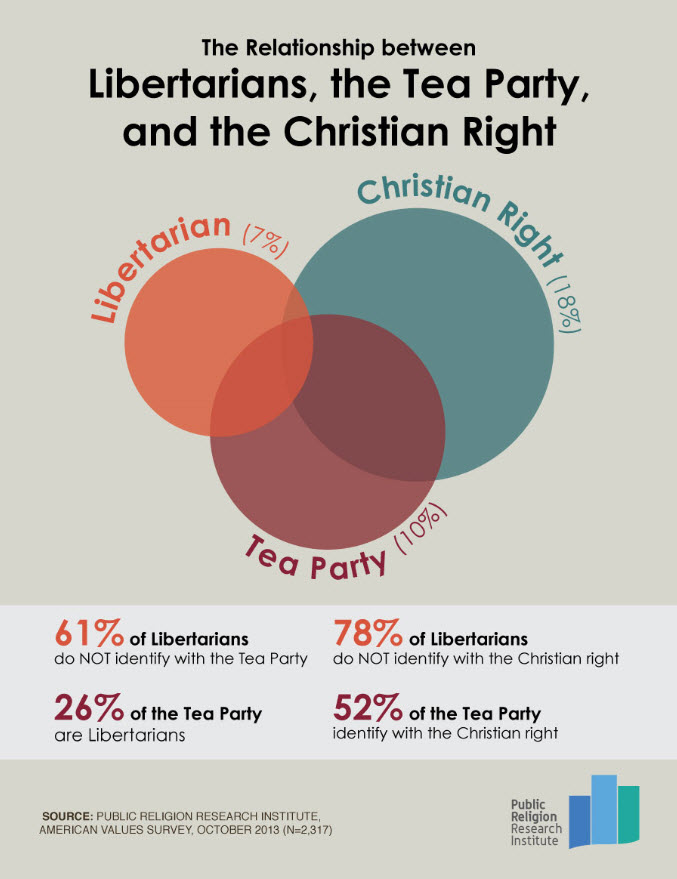

First, according to the PRRI poll, libertarians represent only 12% of the Republican Party. This number is consistent with the findings of other studies by the Pew Research Center and the American National Election Study. This libertarian constituency is dwarfed by other key Republican groups, including white evangelicals (37%) and those who identify with the Tea Party (20%).[1]

While these groups are similarly conservative on economic matters (indeed, libertarians are further to the right than white evangelicals or Tea Partiers on some economic issues, such as raising the minimum wage), they are extremely divided by their views on religion. Only 53% of libertarians describe religion as the most important thing or one among many important things in their lives. By comparison, 77% of Tea Party members say that religion is either the most important thing or one among many important things in their lives, and – not surprisingly – 94% of white evangelicals say that religion is either the most important thing or one among many important things in their lives. A full 44% of libertarians say that religion is not important in their lives or that religion is not as important as other things in their lives. Only 11% of Tea Party members and 1% of white evangelicals say that religion is not important in their lives.

Additionally, libertarians are among the most likely to agree that religion causes more problems in society than it solves (37% total: 17% completely agreeing, 20% mostly agreeing); the least likely to agree that it is important for children to be brought up in a religion so they can learn good values (35% total: 13% completely disagree, 22% disagree); and the least likely to think it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values (63% total: 30% completely disagree, 33% mostly disagree).

These stark differences in attitudes toward religion help explain the large difference in view between libertarians and other conservatives on social issues such as abortion, physician-assisted suicide, and marijuana legalization. Given their positions on these contentious social matters, it is very difficult to envision Libertarians gaining the support of socially conservative voters in the Republican Party.

Libertarians’ influence on the Republican Party is also limited by geography. Libertarians are broadly dispersed across the country – and even where they are most regionally concentrated, they are outnumbered by Tea Partiers and White Evangelicals. According to the PRRI survey, of the 7% of the American public that is libertarian:

- 22% live in the Northeast

- 22% live in the Midwest

- 18% live in the West

- 38% live in the South.

By contrast, of the 10% of Americans who consider themselves members of the Tea Party:

- 18% live in the Northeast

- 17% live in the Midwest

- 22% live in the West

- 44% live in the South.

Of the 18% of Americans who identify with the religious right:

- 12% live in the Northeast

- 22% live in the Midwest

- 17% live in the West

- 49% live in the South.

These numbers strongly reinforce the notion that the South is the center of gravity for the Republican Party, with nearly every major constituency within the party (perhaps with the exception of the business community) seeing its highest levels of support in the region.

According to a study on the ideological compositions of individual states, published by Jason Sorens, a political scientist at Dartmouth College and founder of the Free State Project, the ten states with the largest libertarian constituencies are (in descending order) Montana, Alaska, New Hampshire, Idaho, Nevada, Indiana, Georgia, Wyoming, Washington, and Oregon. By this analysis, the states with the highest levels of libertarian support are predominantly rural, sparsely populated, and share a frontier past, with the partial exceptions of Indiana, Georgia, and New Hampshire.

Of the 10 states that Sorens identifies as having the most libertarians, only New Hampshire, Nevada, and Georgia had spreads of 8 points or less in the 2012 presidential election. The other seven were either solidly red (Montana, Alaska, Idaho, Indiana, Wyoming, and Utah) or solidly blue (Washington and Oregon).

As such, there seems little impetus for any ideological change of course in these states—not to mention the South writ large, the region with the greatest level of libertarian support—since they are already so stoutly Republican. Perhaps in individual districts with a particular libertarian bent, libertarian candidates could have some electoral success. But any candidate running as a libertarian would, by the nature of libertarianism, have to emphasize their laissez-faire values on social issues. If running for higher office, this would surely alienate more socially conservative voters, so strongly represented in the Republican Party in these areas.

The business establishment of the Republican Party would seem a natural libertarian ally, given its moderate views on social issues, opposition to government regulation, and natural sympathy for classical economics. But this view is contested by Henry Olsen of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. At the recent Brookings discussion, Olsen argued that the business community consists of “people who are generally but not intensely opposed to government expansion, people who are generally but not intensely supportive of personal social liberties, people who are generally but not intensely suspicious of intervention abroad. That is the center of the Republican Party, not the libertarian alliance.” The very intensity of the libertarian movement is, as Olsen observed, “a bit off-putting to the person in the middle.”

There is also a kind of limiting syllogism: Though the states with the most libertarians are primarily rural, libertarians are also wealthier than average, better educated than average, and young (indeed, 62% of libertarians are under the age of 50)—three demographic sets that tend to live in densely populated areas. Heavily populated areas are overwhelmingly Democratic. It is not clear how many of voters in these areas would support a more libertarian Republican. Regardless, it is even less likely that libertarianism would tilt the balance in urban counties towards the GOP’s way. Writing in the New York Times, Thomas B. Edsall pointed to a study showing that “98% of the 50 most dense counties voted for Obama. 98% of the 50 least dense counties voted for Romney.”

For a variety of reasons, the burden falls on libertarians to demonstrate how they will change these dynamics. While there may be real appeal for some for Republicans to embrace a more libertarian approach, the undercurrents of the party do not paint an encouraging picture for this as a successful electoral strategy.

The cornerstone of libertarianism—a fervent belief in the preeminence of personal liberty—leads libertarians to hold views on social issues that fall far outside of the mainstream of large portions of the Republican Party. In addition, libertarians’ greatest concentrations in numbers tend to fall either in small, sparsely populated states with less national political power, or among younger individuals who live predominantly in densely populated, Democratic areas. This culminates in an environment where political and demographic forces across the United States and within the Republican Party itself severely limit the power and growth of libertarians as a force within the GOP.

Image source: Public Religion Research Institute

[1] Tea Party members are much more likely to identify with the religious right than they are with libertarianism. More than half of Tea Partiers (52%) say they are a part of the religious right or the conservative Christian movement, and more than one-third (35%) specifically identify as white evangelical Protestants. In contrast, only 26% of Tea Partiers were classified as libertarians on PRRI’s Libertarian Orientation Scale.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Libertarian Challenge within the GOP

December 27, 2013