This analysis is part of The Leonard D. Schaeffer Initiative for Innovation in Health Policy, which is a partnership between the Center for Health Policy at Brookings and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

A buzzword surrounding recent health reform efforts is state flexibility. The House-passed American Health Care Act (AHCA), what’s known about the Senate bill, and other major proposals make prominent use of waivers, block grants, and other tools to give states power to address their unique circumstances.

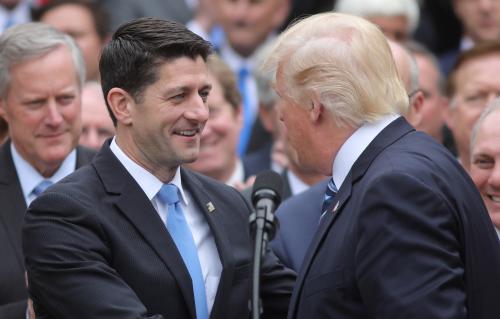

At the same time, concerns have been raised about the coverage losses that would result from the House bill or similar proposals. President Trump and members of his administration have promised legislation that maintains or expands insurance coverage and affordability. Earlier this month, President Trump reportedly criticized the House bill as “mean” and called on the Senate to make its bill more generous.

As Congress struggles to balance the goals of flexibility and adequate health coverage, it’s worth noting that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) already includes a measure that does exactly that. Section 1332 of the ACA allows for “state innovation waivers” that provide broad flexibility for states to redesign their health insurance markets while ensuring that health coverage is not jeopardized.

Section 1332 was the bipartisan brainchild of Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and former Senator Bob Bennett (R-UT). The measure allows states to waive or modify many of the central coverage provisions of the ACA, redirecting the current federal subsidies flowing to the state toward implementing the state’s own plan. To protect individuals, a waiver may be approved only if it won’t leave more people uninsured or make coverage less affordable or comprehensive. A waiver also cannot increase federal deficits.

Section 1332 has received praise from both ends of the ideological spectrum. Last year, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle wrote in the Washington Post that the waivers “can achieve what both sides earnestly wish for: providing more Americans with access to more affordable, flexible, patient-centered health care.” The Trump administration has also been strongly supportive, encouraging states to apply and providing a detailed checklist to help states develop applications.

Action on waivers has been relatively limited to date – largely because they only became available starting in 2017. The only waiver to receive approval so far is Hawaii’s, which frees the state from the requirement to maintain a small business Marketplace (since longstanding state law already achieved the same goal there). Another group of applications, led by Alaska’s, is currently moving through the approval process. These waivers would modify rating rules in the state and draw down federal dollars to help fund a state reinsurance program to both lower premiums and stabilize the insurance market.

These are important measures, and the value of allowing states this kind of flexibility should not be underestimated. But these waiver concepts only scratch the surface of what section 1332 permits. State innovation waivers can be used to make fundamental changes to the ACA’s coverage measures. For example, a state can completely waive the ACA health insurance Marketplace and associated financial assistance and use the money to provide coverage under a state-run program. Waivers can also change the rules for which plans can participate in the Marketplace. A state could even waive the individual and employer mandates so long as it finds another way to achieve broad, affordable coverage.

Given the recent effective date and the evolving federal landscape, states need time to explore options for these more comprehensive waivers. Several states have considered using section 1332 to enact something like single-payer coverage, though cost has been a barrier. Other states like Oklahoma have begun thinking through different kinds of waivers that fundamentally remake the state’s health care system. Overall, eleven states have legislation in place calling for the development of a waiver, and several others are considering it.

As Congress struggles to balance the goals of flexibility and adequate health coverage, it’s worth noting that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) already includes a measure that does exactly that.

Congress could also consider legislation to improve the waiver rules. An important opportunity to add flexibility without jeopardizing coverage is the rules for pass-through funding – money from forgone federal subsidies that would be passed through to states. Under current law, this funding is capped at the amount of forgone Marketplace subsidies, even if the waiver would create additional federal savings. For example, a waiver that reforms the health insurance market to reduce premiums would likely save federal dollars by trimming the cost of the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored coverage. But current law does not allow those savings to be shared with the state. This limitation makes many potential waiver concepts infeasible and does not serve a clear purpose in protecting coverage or the federal budget.

There’s also more the Trump administration could do. One concrete step would be to provide a template or other streamlined mechanism for receiving certain “standard” waivers. A good candidate is the Alaska-style reinsurance waiver, since its direct effects are generally limited to reducing premiums, simplifying the question of waiver approval. States could also benefit from additional clarification about the substantive and procedural rules for waiver approval.

The administration should also ensure that there is adequate staff at HHS and Treasury to help states pursue these waivers. HHS has dozens of staff working on the long-standing section 1115 waiver program, but HHS and Treasury – which share jurisdiction over state innovation waivers – between them have just a few staff positions focused on the section 1332 program. A joint section 1332 office with dedicated staff from each agency could be a good first step.

The desire for flexibility in developing health programs is understandable, even if there is disagreement about how to weigh it against other goals. Each state has unique circumstances that call for different solutions. And states can play an important role in testing different policies as laboratories of democracy, improving our understanding of what works.

But believers in flexibility must recognize that flexibility works both ways. Many states that have embraced the ACA have flourished under it, with robust insurance markets and large reductions in the number of people uninsured. For these states, legislation that removes the ACA’s coverage provisions as an option – like that being considered currently in Congress – is the opposite of flexible. (The AHCA would also undermine state innovation waivers by greatly diminishing federal health insurance subsidies and thus the potential pass-through payments to states.)

And this highlights the best thing about state innovation waivers. States that like the way the ACA works can keep it as is. States that want additional flexibility can receive federal funding to try out something different.

Before rushing to pass sweeping legislation in the name of flexibility, Congress should take a closer look at the flexibility state innovation waivers already provide.

Jason A. Levitis is a Senior Fellow at the Yale Law School’s Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy. Until January of 2017, he led ACA implementation at the U.S. Treasury Department. In that capacity, he co-chaired an interagency work group charged with implementing the state innovation waiver program.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Want states to have health reform flexibility? The ACA already does that

June 21, 2017