The tangled web of Greek finances is a long-running saga whose current chapter is complicated. However, glimmers of relief are beginning to appear. Bright spots include the likely endorsement of the Greek budget by the Eurogroup on December 3. Yet, all is not sanguine and EU officials should avoid wearing rose colored glasses when it comes to Greece’s medium-term growth prospects.

On November 21, the EU Commission issued its first post-program enhanced surveillance report, postponing the release of 600 million euros to Greece. The funds link to two sources—the European Central Bank’s Securities Market Program (SMP) and the Agreements on Net Financial Assets (ANFA). They constitute an SMP/ANFA tranche. (ANFA is an agreement between the national central banks (NCBs) of the euro area and the ECB. The agreement sets rules and limits for holdings of financial assets made independently by the NCBs. The SMP purchases debt securities by the ECB as a way of helping member countries (like Greece) transition smoothly out of debt-distress.)

The delay of the SMP/ANFA tranche to Greece, among other stalled reforms—like the lack of progress in privatizations and arrears-clearance delays equivalent to about 3 billion euros—will cost the country dearly.

On the plus side, when the Eurogroup convened on November 19, the previously legislated “personal difference” pension cut was suspended. This preserves the extra money—around 2.0 billion euros, or almost 1 percent of GDP—given exclusively to pensioners who retired before the 2016 pension law came into force. The figures below show the dramatic fall in Greek wages (blue line) since inception of the crisis, compared to the slight decline in pensions during the same period. Figure 1b shows a possible number of pensioners who will benefit.

According to the mid-term 2019-2022 program agreed with the European creditors, the share of public sector wages in the budget increased from 15.6 billion euros in 2015 to 17.1 in 2018 and to 17.6 billion euros for 2019, as projected in the budget tabled at the parliament last week. It is thus evident that the government aims to extract political gains from throwing a proverbial bone to pensioners and public servants. Officials also hope to maintain a certain level of demand as they struggle to boost Greece’s economic growth in the face of a 183.1 percent debt-to-GDP ratio.

At the same time, the primary surplus for 2018 is projected 4.2 percent GDP for the third year in a row. The surplus arose at the expense of much-needed public investments, which were already trimmed by 300 million euros compared to original projections included in Greece’s 2019-22 medium-term fiscal strategy.

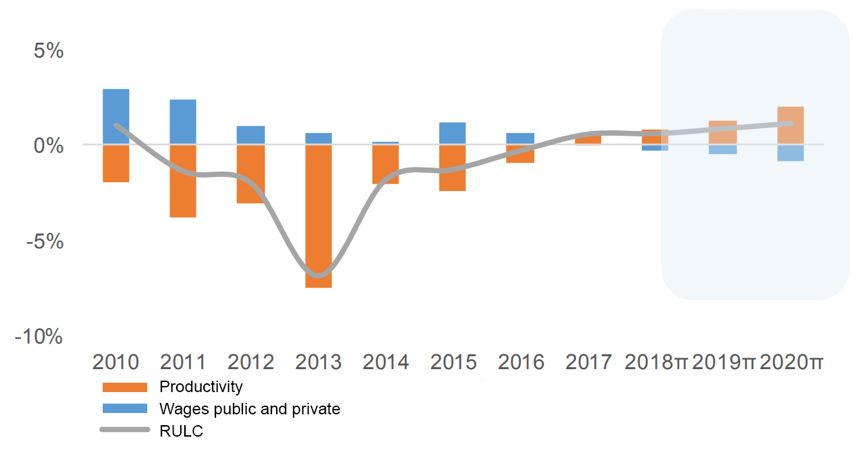

The curtailment of public investments continues to undermine Greece’s GDP growth prospects, productivity, wage levels, and net employment. As for the critical issue of productivity in particular, a November 23 report from Alpha Bank correctly emphasizes that as productivity falls more steeply, the resulting increase of the unit labor cost is hurting competitiveness.

Figure 2. Productivity and real unit labor cost (RULC)

Likely passage of the Greek budget

Signs predict that the Eurogroup meeting on December 3 will endorse the Greek budget. Eurogroup President Mario Centeno has already declared that Greece reached the targets set by the last summer’s agreement between EU creditors and the Greek government, despite the lackluster report of the EC regarding the progress of reforms in the context of the enhanced post-program surveillance.

However, it is not only this negative report that seems to send wrong signals to the markets. To achieve a primary surplus of more than 4.0-4.2 percent (instead of 3.5 percent, as agreed with creditors), the government draws from public investments, which further deteriorates long-term growth prospects.

A way out of the current conundrum

Given current constraints created by the primary surplus requirements, the best medium term policy (through 2022) would entail three steps:

- Vote into law the reforms agreed and get the 600 million euro tranche immediately,

- Undertake direct clearance of arrears,

- Avoid any extra primary surplus (above 3.5 percent) from 2019 onwards. (Unfortunately, the government in its MTFS 2019-2022 tabled last June featured a primary surplus of 5.2 percent for 2022!).

Satisfying these priorities could help de-escalate 10-year Greek Government Bond (GGBs) spreads, which have climbed to 420 basis points (the interest rates on such bonds are currently around 4.5 percent). This would effectively deny the country market access. The three steps might also give a substantial boost to the economy well above the current estimated 1.5-2.0 percent GDP growth rate. The measures would also leave consumers with more money to spend or to invest. Moreover, more disposable income for those who have borrowed heavily from banks will help such financial institutions reduce their sky-high non-performing loans.

Political expediency may win out over fiscal prudence

Yet in the face of decreasing public support and elections slated for some time next year, the government seems inclined to set different policy and fiscal priorities at the expense of long-term, sustainable growth. Strange those EU creditors are not intending to react.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Greece: A postponed tranche, relief for pensioners, and likely budget endorsement

November 29, 2018