This article is part of the Brookings Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative’s “Digital Prosperity” blog series, which examines how regions across the country are using innovative strategies to respond to a range of digital inclusion challenges.

Every region across the country experiences some level of digital disconnection. This can range from Brownsville, Texas, where just half of households have an in-home broadband subscription, to Portland, Ore., where all but a few pockets of homes are connected.

Many more communities, such as Louisville, Ky., fall somewhere in the middle. In Louisville, most households have access to broadband and pay for a subscription, but neither is universal. This leaves the city’s Office of Civic Innovation and Technology with a clear mission to overcome barriers to digital equity. However, there are often not enough resources to fully address the issue.

The story of Louisville is one of identifying existing resources, building relationships, and continually planning for the next step.

The city of Louisville houses 767,154 people, which represents the combined population of the historic city boundaries and its formal merger with Jefferson County as a unified government. The city/county represents almost half of the larger metro area population of nearly 1.3 million. Though the city’s median household income ($54,357) is below the national average, and the poverty rate (14.8%) is above it, the metro area has seen economic growth and prosperity outpacing the national average over the past decade.

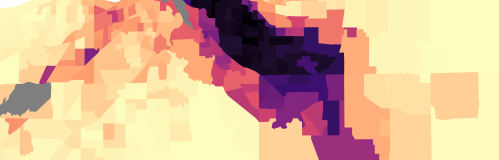

Both the historic city of Louisville and the Louisville-Jefferson metropolitan area have close to universal broadband access, with the internet service provider Spectrum offering high-speed cable broadband to more than 95% of residents, according to FCC data from June 2018. The percent of residents living in blocks with 25/3 Mbps speeds offered by two or more providers (Spectrum and AT&T) in 2018 was about 91% for historic Louisville and 85% for the entire county.

Yet even with expansive service, not all households have broadband subscriptions. The latest Census Bureau data indicates that 13.5% of households in historic Louisville lacked home broadband subscriptions of any kind, and an additional 14.3% of households lacked wireline broadband at any speed. The disconnect is closely tied to income: About 33% of Louisville city households with annual incomes below $20,000 had no home broadband of any kind. These accounted for 20% of all households but 45% of those without broadband. In contrast, all but 4% of households with incomes above $75,000 had some type of broadband subscription.

FCC data also confirmed the areas that did not have broadband at 25/3 Mbps speeds or greater were concentrated in lower-income neighborhoods surrounding downtown, and to the west and southwest.

In 2017, Louisville released a Digital Inclusion Plan referring to “fiber deserts” in neighborhoods in west and southwest Louisville, which also have the city’s highest unemployment rates. “These previously unrelated issues of employment and broadband access are now intertwined and are most likely, based on research, affecting outcomes for our citizens,” the plan stated.

The Digital Inclusion Plan identified lack of technology access and use as an issue that must be addressed. Louisville’s Office of Civic Innovation and Technology was created in 2019 to solve these challenges. With no project budget and no dedicated staff, the new office focused efforts on promoting discounted AT&T and Spectrum internet offers. The first step was to attend community gatherings such as back-to-school events and job fairs to inform and sign up individuals who were likely to be eligible (families with children receiving free/reduced lunches, seniors receiving supplemental security income, and households receiving SNAP benefits). Then they recruited volunteers to do the same and expand the office’s reach.

They also developed relationships with organizations providing services to low-income community members. Louisville worked with Goodwill Industries of Kentucky and the Louisville Metro Housing Authority to set up digital literacy training courses and computer labs. The office acquired donated computers which they and partners refurbished. Goodwill and the Housing Authority donated space and staff time.

In 2019, to identify new digital inclusion strategies for Louisville, the metro government established a research partnership with the local chapter of the Interaction Design Association (IxDA). The partnership’s goals were to understand how people without high-speed internet at home are accessing the internet now, how they use it, and what changes for them after they gain access. They also wanted to discover how to improve the sign-up process for low-cost internet services and where to increase awareness of low-cost internet and other digital inclusion services.

The results were illuminating. After conducting interviews with residents, the partnership identified four systemic barriers: a lack of awareness of home internet options, a lack of basic technology skills and stigma around asking for help, a challenging sign-up process for low-cost internet, and associated challenges involving financial assets, bureaucratic trust, and transportation limitations. Those findings are now informing a set of strategies to directly address these barriers and the needs of disadvantaged and disconnected households.

This commitment helped increase formal adoption of digital equity strategies. In 2019, the Office of Civic Innovation and Technology hired a permanent program manager focused entirely on digital inclusion. Past research results—plus Louisville’s relationships with Goodwill, the Metro Housing Authority, and other local partners—are all informing development of the metro area’s next steps.

Louisville’s journey to digital inclusion for all of its citizens has just begun. But the city’s leadership has made an exemplary commitment to pursue digital equity as a true community priority.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Louisville, Ky. is leveraging limited resources to close its digital divide

April 16, 2020