The mathematical models of economic theory have always sacrificed a bit of on-the-ground accuracy for what has been assumed to be a larger measure of insight. Work on how local labor markets respond to shocks like mass layoff events and recessions is a case in point. While the near-term pain of these shocks has raised more and more questions, the conventional wisdom of a relatively benign “adjustment” period over the medium-term has largely survived. The general consensus: Workers and local economies will adjust. Dislocated workers will leave distressed regions and move to healthier ones. Jobless rates will revert to the mean.

Yet it now appears this consensus view of dislocation and recovery is breaking down.

In the last six months a burst of new empirical work—much of it focused on the region-by-region aftermath of the Great Recession—is shredding key aspects of the standard view and suggesting a much tougher path to adjustment for people and places.

Overall, the new research—notwithstanding general “equilibrium theory” and the notion of the business cycle—shows that the reality of adjustment is far from automatic, far from quick:

- In much-discussed new research on the local impacts of trade touched on the other day by my colleagues Joe Parilla and Amy Liu, David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson focus on the “stunningly slow” adjustment of exposed local labor markets to the “China shock” and argue that the story challenges “much of the received empirical wisdom about how labor markets adjust to trade shocks.” Autor and his colleagues do not see much evidence at all of a frictionless labor market in which the rapid mobility of workers across firms, industries, and regions guarantees rapid adjustment to new realities. Instead they see a series of slow-moving crises in particular metro areas. “Switching costs” and other frictions inhibit workers’ ability to shift quickly to new, less-threatened firms or industries. Many workers never recoup lost earnings and depend more on transfer payments. Little offsetting growth is detected in industries not exposed to the shock. Autor and his co-authors—who support trade—call for a “more convincing” assessment of the benefits and adjustment challenges of trade shocks.

- Turning to migration, another form of adjustment, Andrew Foote, Michael Grosz, and Ann Huff Stevens recently confirmed that whereas worker out-migration has typically been a major part of labor market adjustment things did not work that way during the Great Recession. Few people moved away from the scene of mass layoff events, perhaps because the housing crisis impeded mobility. Far more frequent was non-adjustment: settling into non-participation in the labor force, which explained 67 percent of the net labor force change prompted by the mass layoff events.

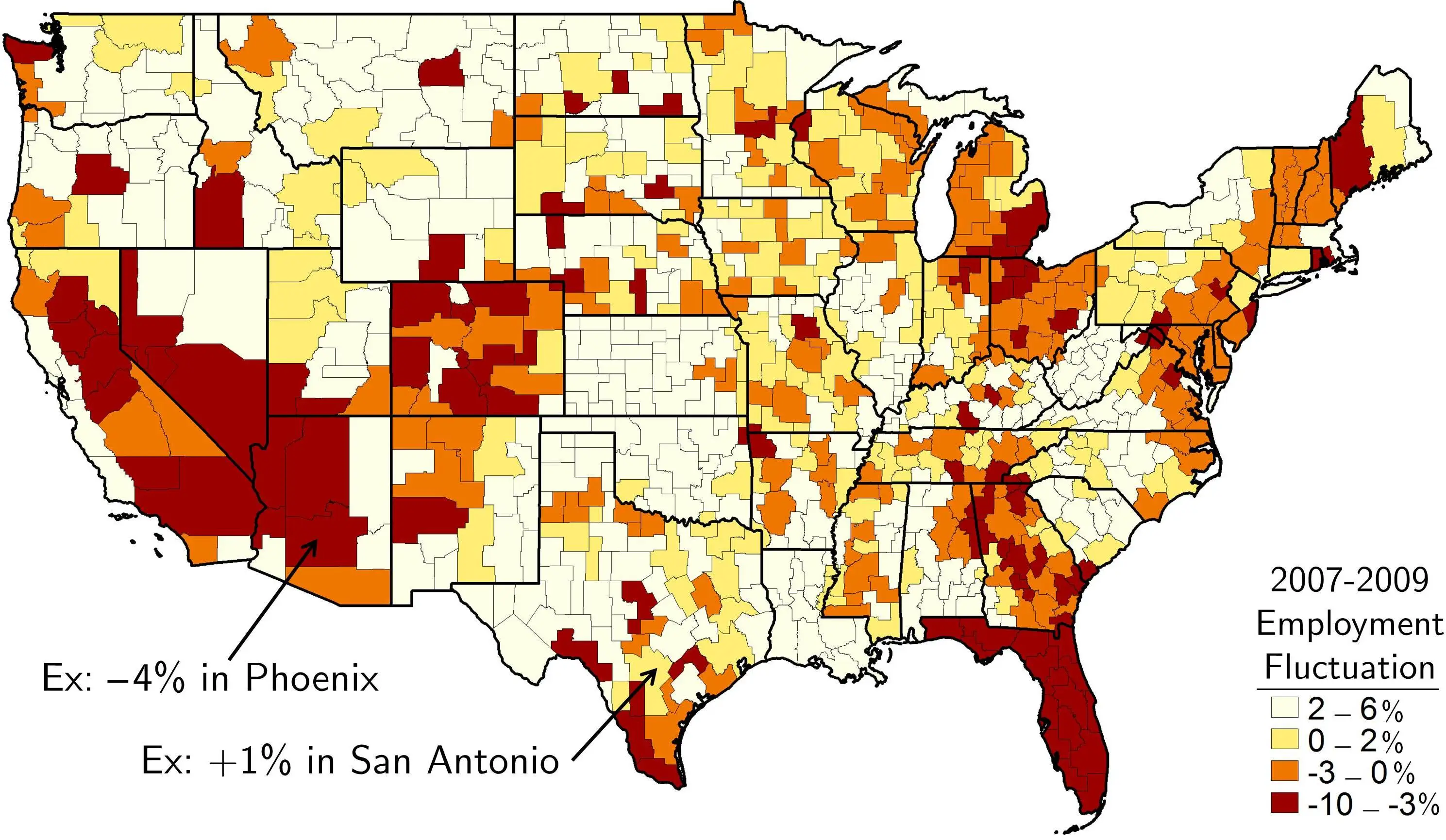

- And finally, Danny Yagan reported last month that whole regions are struggling to adjust in the wake of the recession. Even factoring in out-migration, employment remains depressed in severely affected metro areas even nine years later. In fact, adjustment is occurring so slowly that at the current pace of normalization, employment rates across the United States won’t return to normal levels until the 2020s, “amounting to more than a relative `lost decade’ of depressed employment for half the country.” Part of the problem: Displaced workers, as per Foote and colleagues, haven’t been moving.

Source: The Enduring Employment Impact of Your Great Recession Location

As to the upshot of this work, it’s increasingly clear that policymakers need to be thinking much more urgently about how to provide for and accelerate adjustment for the victims of economic shocks.

Some of that thought should go into strengthening the nation’s ineffectual Trade Adjustment Assistance program. Grossly underfunded, the program provides only puny financial and transitional support to workers who have been displaced by foreign competition. And while assistance with retraining would seem essential, not many of those who lose jobs because of trade actually receive training through the program.

Yet the problem is much broader than that. Given the growing variety of labor market stresses, ranging from recessions to automation, the nation needs broader safety net and transition programs—a point that was made well in January by the Council on Foreign Relations in a report entitled, “No Helping Hand: Federal Worker-Retraining Policy.” The Affordable Care Act, with its insurance subsidies for those who have lost jobs, is a start, but the nation, states, and regions need to do more to retrain displaced or vulnerable workers for jobs in expanding industries. Likewise, the limited wage-insurance program in TAA needs expansion into an omnibus national program through which the government would help workers maintain their wage level while they train for and start new jobs. And maybe the limited reimbursements for moving costs in the TAA should be expanded into a more robust provision of aid to help displaced workers move to cities or states where jobs are more plentiful.

In this respect, recent calls for a basic income—while not yet part of the thinkable consensus—certainly reflect broader concerns about adjustment in all of its forms as the pace and scale of disruptions grow.

In any event, it’s time to get real about the grittiness of adjustment. Adjustment happens, but it’s a far more painful process than the models and textbooks have imagined. Policy, and the economists, should take it seriously.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Adjusting to economic shocks tougher than thought

April 18, 2016