From burst pipes in Syracuse, N.Y. to chemical contamination in West Virginia and Ohio, America’s drinking water systems face a growing list of maintenance and investment challenges. Perhaps surprisingly, one big challenge is simply the sheer number of systems.

The United States has over 51,000 community water systems (CWS), which provide public water to more than 300 million people. That averages out to about 6,000 people per system, but few systems are average: 28,300 “very small” systems serve populations under 500; another 13,700 “small” systems serve 501 to 3,300 people; and 4,900 “medium” systems serve 3,301 to 10,000 people. As a result, the vast majority of public drinking water facilities serve a relatively small portion of America’s population.

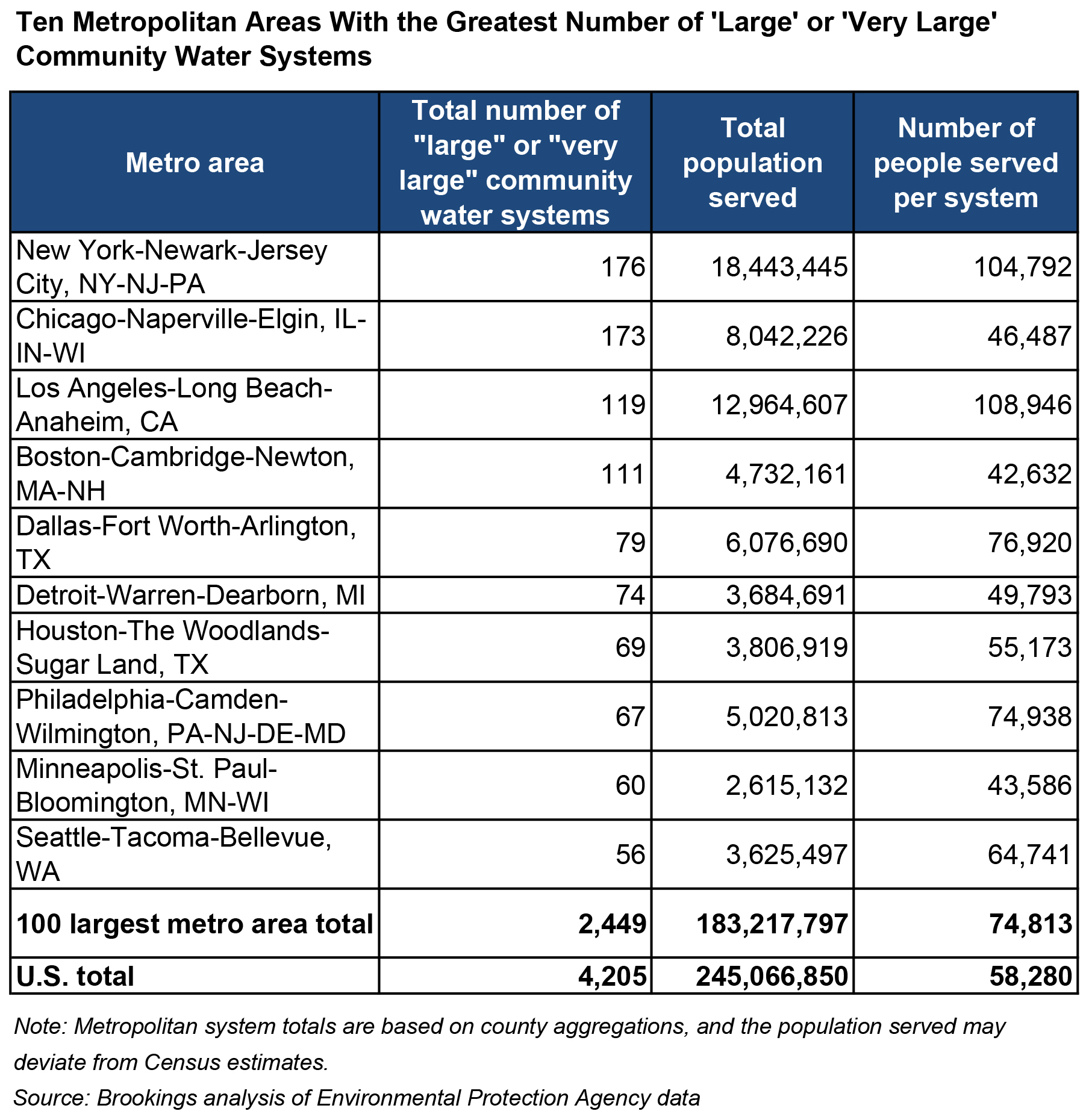

The remaining 4,200 “large” or “very large” CWS serve more than 246 million people, or 82 percent of the population, and tend to have the biggest impact on drinking water needs in the most productive markets. The country’s 100 largest metropolitan areas contain 2,449 of these 4,200 enormous community water systems, for an average of about 25 systems per market. When added to the thousands of smaller CWS, these systems form a complex web of public drinking water infrastructure that can lead to widespread governance challenges at a regional level.

Serving almost 70 million people, 984 large and very large systems are located in 10 metropolitan areas alone, led by New York (176), Chicago (173), Los Angeles (119), Boston (111), and Dallas (79). Even smaller metro areas like Dayton, Ohio, McAllen, Texas, and Greenville, S.C. can have up to a dozen or more big water systems, requiring extensive coordination among local leaders to address long-term infrastructure needs.

Not surprisingly, the most populated metro areas depend on more systems overall, but the number of people served per CWS can vary widely, leading to additional fragmentation and potential inefficiencies. For example, each large and very large system serves about 58,000 people on average nationally, but service in several markets is more fragmented. In Detroit, for example, each CWS serves an average of 49,793 people, and the metro area continues to struggle with a backlog of repairs and regional dysfunction. On the other hand, areas like Philadelphia (74,938 per CWS) have been able to benefit from a more consolidated and interconnected network.

A sprawling drinking-water system brings with it a number of planning and investment hurdles. At the same time innovations in water efficiency, quality, and reliability must come increasingly from state, local, and private leaders, as the federal government funds less than 1 percent of the $61 billion spent on water infrastructure annually. Installing smart meters and introducing new block rate structures, for instance, can help squeeze more efficiency out of existing systems, while the consolidation of individual utilities and public-private partnerships can further reduce costs. Given clean water’s crucial role in economic development, metros adopting these strategies are well-positioned to succeed in the future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Water systems everywhere, a lot of pipes to fix

July 2, 2015