Yes, I know: social mobility is not the first thing that springs to mind when you think of the United Kingdom – more likely it will be the hereditary monarchy, expensive soccer stars, or Downton Abbey.

But in recent years, the challenge of improving intergenerational mobility has seized the British political class, as a result of depressing academic research, growing concern about inequality, and the laser-like focus of one think-tank in particular, the Sutton Trust (which is currently holding a joint summit on teaching with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Washington DC).

Handling the (Often Painful) Truth: A New Commission

One tangible result was the creation, in 2012, of an independent, statutory Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission (Disclaimer: I was involved in my previous role). Headed by a former Labour Party politician but with cross-party membership, the Commission publishes annual reports on the UK’s progress on both poverty and social mobility.

In its latest 260-page report, the Commission gives an upbeat appraisal of the overall economic situation, employment rates, and the rise in the proportion of low-income adults attending college (despite a rise in tuition costs). But the Commissioners do not pull their punches on other fronts, describing the government’s failure to revise its poverty measures as ‘lamentable’ and warning of a ‘bleak outlook’ for both mobility and poverty unless radical action is taken. Remember: this is a Commission that the government chose to establish, in order to hold itself and others to account. So, credit where it is due.

The report is also bursting with ideas: a Living Wage, universal parenting classes, further devolution of power to major cities, higher pay to good teachers in challenging schools, and so on. But perhaps the most provocative is the abolition of unpaid internships in the professions.

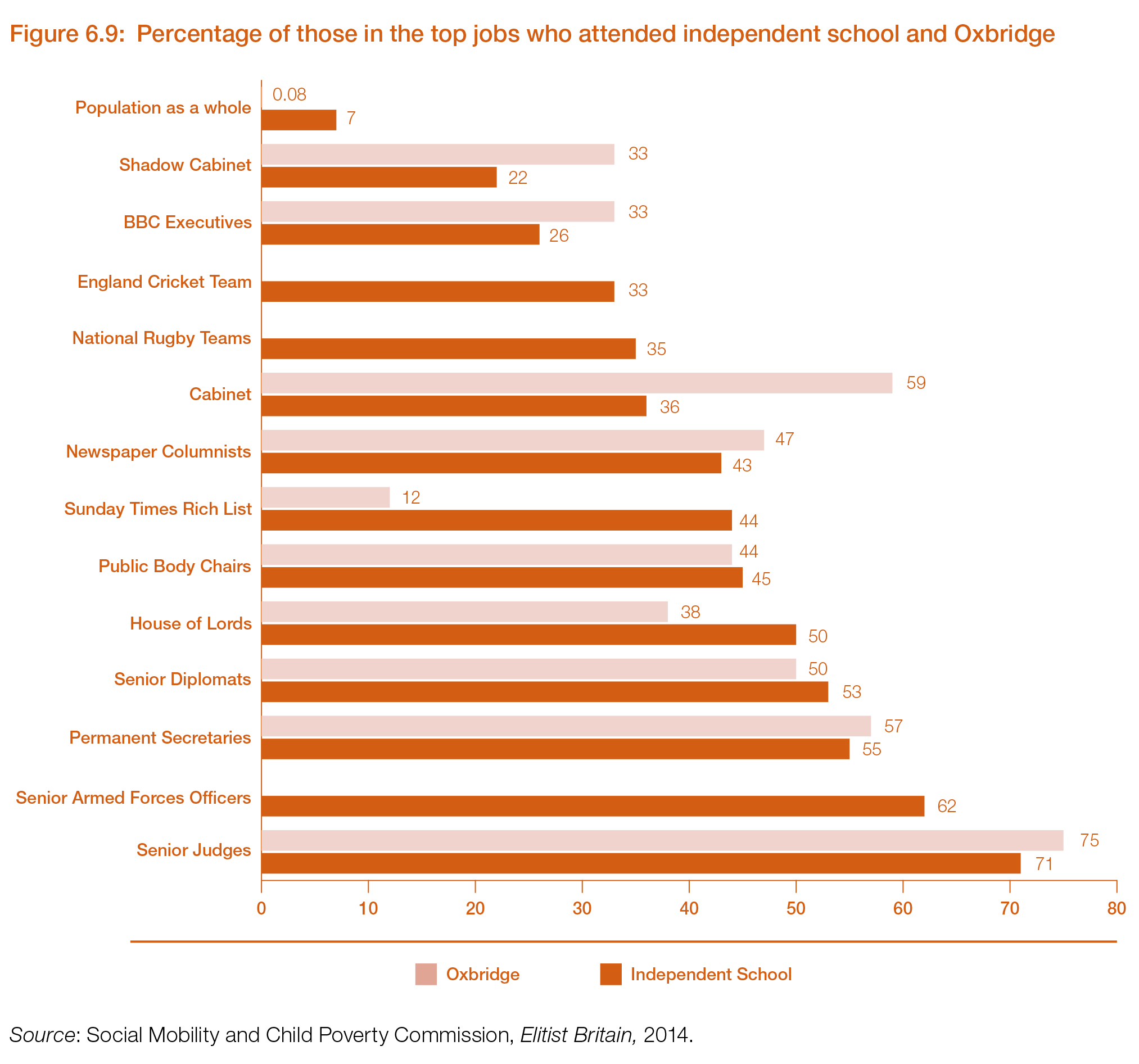

The Commission has focused a good deal of attention on the lack of broad social representation in the top professions and other areas of national life – an earlier report was titled simply Elitist Britain. The Commission is worried about the over-representation of those from private schools (K-12, that is) and from either Oxford or Cambridge (‘Oxbridge’) in the top-tier:

Unpaid Internships Equal Elitism: So Ban Them?

Unpaid internships contribute to the ‘elitist’ make up of medicine, the law, and journalism, according to the Commission. For example, 83 per cent of new entrants to journalism have done an internship, lasting around seven weeks, and 92 per cent of these are unpaid. (This particular finding was not widely covered in the British media, oddly enough.) The Commission calls on professional bodies to end the recruitment of unpaid interns by 2020, and adds that “if rapid progress is not made legislation banning unpaid internships should be introduced”. This seems radical even by European standards of government regulation, let alone in the US. But if internships represent an increasingly important ‘opportunity hoarding’ mechanism for the affluent, radicalism might be required.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Social Mobility: Can the U.S. Learn from the U.K.?

November 4, 2014