Differences in parenting behavior can exacerbate other inequalities, such as those in income and education. Take breastfeeding, for example. There is solid medical evidence that breast is better than bottle, for both mother and child.

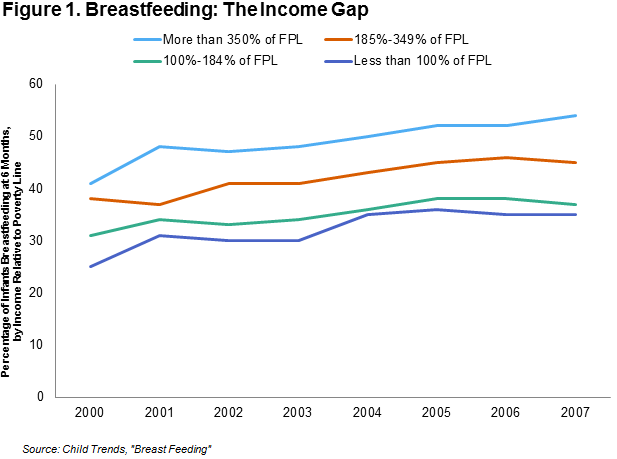

Good news: breastfeeding rates are rising. Bad news: the gap between low-income and high-income parents remains wide, contributing to gaps in life chances for children. Mothers below the poverty line are 19 percentage points less likely to breastfeed than mothers 350% above it.

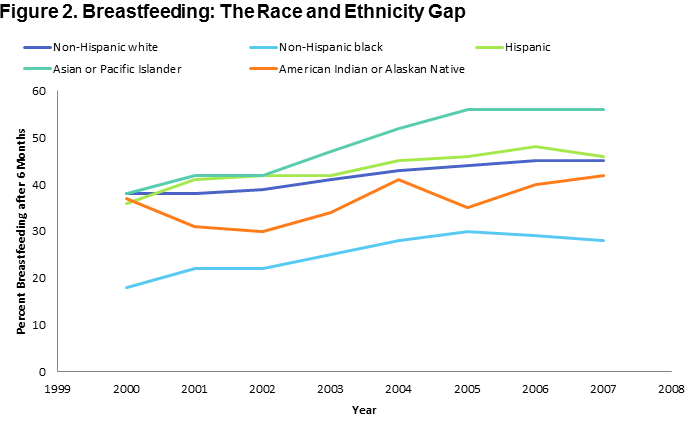

There are also significant gaps along racial and ethnic lines:

Source:

ChildTrends

A Mother’s Milk: Good for Life Chances

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers feed their babies exclusively with breast milk until they are at least six months old. Research links breastfeeding with reduced risk of developing allergies, infections, obesity, and diabetes. For mothers, breastfeeding may reduce the risk of cancer and bone fractures. It is important not to overstate the case, however: a recent sibling study from researchers at the Ohio State University finds that these benefits, while real, may be more marginal than previously believed.

WIC: Struggling to Strike the Balance on Breastfeeding

The Women and Infant Children (WIC) program, which serves new, low-income mothers, calls breastfeeding the “optimal infant feeding choice.” But it’s also the world’s largest single provider of infant formula—at no charge to clients. WIC children – fifty-three percent of American infants, according to the USDA – are, unsurprisingly, more likely to be fed with formula.

In Dallas, if mothers forgo WIC’s breastfeeding-only plan, WIC provides 9 of the 13 cans an infant is likely to need in a month. These same WIC clients are required to take a breastfeeding class. WIC is promoting breastfeeding while providing free formula. The formula fulfills a real need among clients, but health advocates wish breastfeeding were more popular, and that formula less readily accessible.

It is not just economics at work, but history and culture too. When WIC began in 1974, many American children suffered from afflictions common in developing countries today: anemia, iron deficiency, and acute malnutrition. For many, baby formula represented a nutritional leap forward. The benefits of breastfeeding were less, and less well-known.

Closing the Breastfeeding Gap

Nursing mothers will have new rights to feed and pump in the workplace, under the Break Time for Nursing Mothers law, a little-noticed element of Obamacare. Ensuring that these rights become a reality – and also that women do not suffer discrimination as a result of them – is a priority.

But there is a broader issue here, about the lives and stresses of working mothers, especially those on low incomes. Many have low-wage jobs with long hours, long commutes, unpredictable schedules, and few benefits. Breastfeeding takes time; the U.S. skimps on maternity leave by OECD standards. Breastfeeding takes help; the U.S. pushes new mothers out of hospitals quicker than almost all other OECD countries. Other governments offer free nurse visitation; here, many mothers are left to figure it out alone. So: affluent mothers breastfeed, poorer mothers often rely on formula, and the cycle of inequality worsens.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Nursing Opportunity: Class Gaps in Breastfeeding and Policy Challenges

September 10, 2014