Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

Iraq is beset with crises. In the scorching summer heat, the country is suffering from electricity and water shortages, longstanding challenges that have routinely resulted in violent protests as part of wider grievances around lack of services and rampant corruption. On July 12, a hospital fire killed at least 60 people as a result of negligence and mismanagement. On July 19, the Islamic State group (ISIS) carried out a deadly attack, killing at least 35 people in Baghdad. In the midst of all this, Shiite militia groups tied to Iran routinely assassinate civilians and activists, and use rockets and drones to attack U.S. personnel, Iraqi military forces, and U.S.-aligned actors like the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who came to office last year with the expectation that he will secure some respite for the Iraqi population, presides over a perilous political and security environment. The space could soon emerge for an ISIS resurgence, and with that a catastrophic convulsion that could unfold if Iraq is yet again caught between incessant attacks by ISIS and Iranian proxy groups which have been responsible for systemic, near-daily human rights atrocities.

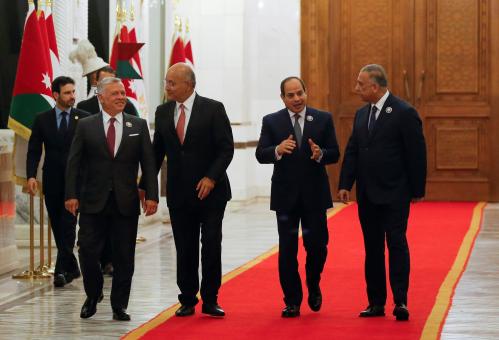

Thus, Kadhimi’s visit to Washington and Oval Office meeting with President Joe Biden this week was highly opportune and important. The two leaders announced that the U.S. will fully transition to a training, advising, assisting, and intelligence-sharing role in its security relationship with Iraq, and that by December U.S. combat forces will no longer be deployed. While that may constitute a cosmetic change — the U.S. does not have combat forces in Iraq — it aims to address the pressure that Kadhimi is under to placate Tehran and its Iraqi proxies, which demand the withdrawal of U.S. forces and have recently escalated their attacks on U.S. targets and allies. Kadhimi must balance these demands with Iraq’s continued dependency on U.S. support to combat ISIS and reconstruct the economy after years of conflict and devastation.

Shiite militias: a terrorist threat

Iraq faces a potential moment of reckoning that could mirror the events that unfolded just seven years ago when ISIS seized a third of the country. The U.S. remains integral to the painstaking campaign to combat ISIS, which has ramped up attacks in recent months. The group is co-opting, extorting, and coercing communities to establish the infrastructure that allowed it to seize large swathes of territory in 2014. Without continued U.S. military support, the jihadis may revive their so-called caliphate.

The necessity of defeating ISIS cannot be overstated, but one of the more understated enablers of the group’s preeminence is the continued dominance of Shiite militia groups tied to Iran. They directly undermine the government by attacking its security forces, while also enabling ISIS through the casualties they inflict on the Iraqi population. Responsible for killing more than 600 Iraqis tied to the protest movement, for wounding thousands, and routinely assassinating or kidnapping activists, Iranian proxy groups are turning Iraq into a republic of fear.

They hold the state hostage through the barrel of the gun while enjoying constitutional legitimacy as members of the Popular Mobilisation Force (PMF), which has access to a federal budget worth at least $2 billion. They also exploit the religious legitimacy that was bestowed upon the PMF by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in 2014, when the organization was formed to fill the void left by the collapse of the army. Since then, those groups that were aligned with Ayatollah Sistani and not tied to Iran have left the PMF, out of protest against their human rights atrocities and abuse of power.

Seventy-seven percent of Iraqis, including 76% in Shiite areas, are skeptical that forthcoming elections, scheduled for October, will deliver accountability and justice because of the control Iran-aligned militias have over the political environment. The despair is such that there are growing calls for a boycott, which could produce a re-run of the 2018 elections that were tainted by fraud and saw a coalition led by Iran-aligned groups finish second on its electoral debut. Since then, the Iraqi state has been in a state of crisis not seen since ISIS seized Mosul. Tens of thousands have protested against Iranian proxy groups to no avail and at great human cost.

Iraq and the United States: Fighting the same war

Washington’s counterterrorism strategy in Iraq is focused on the enduring defeat of ISIS. But like Iraq, the U.S. is also engulfed in a war with Iran-aligned militias, with its bases in Iraq coming under attack on at least seven occasions in July alone. Washington has tried to find ways to counter malign Shiite militia groups and their affiliates, but their integration into Iraq’s political system and society does not yield itself to the deployment of the same tools used to combat ISIS.

By formally treating Shiite militia groups tied to Iran as the equivalents of ISIS and establishing policies accordingly, the U.S. and its allies could at least start to begin the process of developing the parameters for combating these groups in a manner that is both viable and sustainable. Senior Iraqi officials have already started classifying these attacks as terrorism, while the Biden administration has struck Iran’s proxies on at least two occasions since taking office. The change in rhetoric from the Iraqi side and the proportional strikes from the U.S. is welcome, but formally treating Iran’s proxies as the equivalents of ISIS would establish a sense of direction and purpose to future U.S. military responses to militia attacks and the wider question of how the U.S. should engage Iran’s proxies; a signal of intent that has been missing and that could reinforce U.S. deterrence.

This is in contrast to the current approach of ad-hoc retaliatory measures, in response to a set of attacks and not as and when the attacks occur. Iranian proxy attacks should not be treated as anomalies and symptoms of the breakdown of order in Iraq. This diminishes the imperative of containing these groups and puts them in stronger stead. Far from being symptoms, Iranian proxy groups are the problem itself and directly responsible for the terror and tumult in the country.

Establishing (and protecting) political alliances

During this week’s meeting, Biden and Kadhimi struck the right tone aimed at satisfying opponents of U.S. troop deployments in Iraq. To make U.S. counterterrorism support count — and to strengthen the case for continued deployments beyond December — the heavy lifting has to be done by America’s allies within Iraq. However, these allies must establish a grand bargain among themselves that will shore up their attempts to keep U.S. forces in the country and establish a buffer against the influence of Iran and its proxies. They are too often focused on their own rivalries, which inhibits their capacity to decisively shape the political landscape, in contrast with the far-more organized, disciplined, and strategic bloc of Iraqi actors that Iran has cultivated and managed.

Washington should make it a priority to steer Iraq’s U.S.-aligned political actors toward a grand bargain that they are unlikely to reach on their own. The U.S. has helped the KRG and Baghdad improve relations since Kadhimi and KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani came to office. A broader effort would draw on the values and objectives that bind U.S.-aligned actors and establish sustainable dispute resolution mechanisms.

Treating Iran’s proxies as the equivalents of ISIS, combined with a formidable U.S.-aligned bloc in Iraq, could enhance the Biden administration’s credibility and negotiating hand with Iran, for both nuclear talks and regional de-escalation efforts. In practice, and combined with continued U.S. strikes on Iran’s proxies, it means increasing the risk calculus for individuals that lead or dominate Iran’s proxy groups, establishing a threat that is credible enough to constrain their malign conduct. It also requires expanding the scope of sanctions and terrorism designations to include Iran-aligned groups responsible for rocket attacks and other human rights abuses — and to impact those directly or indirectly tied to these actors. This would suppress the proxies’ ability to form the cross-party alliances integral to their political ascendancy and leverage.

While the U.S. cannot eliminate these groups and their infrastructure, it can start focusing its efforts more on the individual, rather than the organization: this should include ending funding and institutional support for the Iraqi institutions that are dominated or controlled by individuals or groups that answer to Iran. Domestically, that will help create an equilibrium and prevent Iran’s proxies from expanding their hold further.

This is where the prime minister comes into the picture. Since coming into office, Kadhimi’s leadership style and posture has contrasted starkly with those of his predecessors, who either came into or left office with a blood-stained and conflict-ridden relationship with their rivals and the Iraqi population. Kadhimi lacks the domestic and geopolitical baggage that shaped his predecessors’ ties to regional powers. But Kadhimi — a compromise prime minister — lacks a political base, and it is here where the U.S. can help him secure another term, an opportunity Washington and its allies should seize.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Treat Iraq’s Iran-aligned militias like ISIS

July 30, 2021