President Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe have plans to see much of each other this spring. The Japanese leader visited Washington last April to discuss key issues in the U.S.-Japan relationship (coordination on North Korea, and the scope and timeline for bilateral trade talks), but also strategically timed the visit to pay an important social call: celebrating the first lady’s birthday.

On May 25, President Trump will go to Japan for a four-day state visit. Tokyo will pull out all the stops to shower the American president with honors and distinctions. Not only will he be the first world leader to meet the newly inaugurated Emperor Naruhito, he will also have the chance to award a specially designed trophy at the Summer Grand Sumo Tournament (informally dubbed as the “Trump Cup”), and is scheduled to tour Japan’s Izumo aircraft carrier.

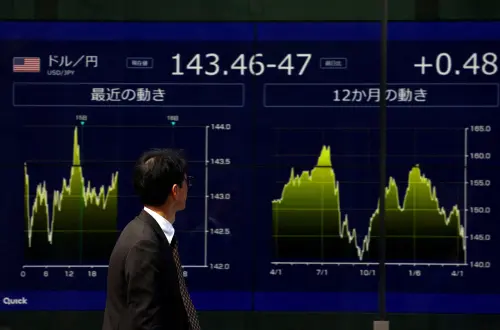

Next month, President Trump is expected back in Japan to attend the leaders’ summit of the G-20, the first ever Japan has hosted. The Japanese city of Osaka may well provide the venue for a Trump-Xi meeting that could be pivotal in the American president’s decision on whether to escalate the trade war by taxing the entirety of Chinese imports coming into the United States.

Three meetings in three months is an unusual pace for international summitry.

Three meetings in three months is an unusual pace for international summitry, even for two leaders who are good friends. In fact, it is the hallmark of good friendships that they can withstand distance. And so, the series of high-level meetings should be seen as the result of both close bonds among the two leaders and Japanese anxiety that “America First” could trample core interests of Japan. Just this month, statements from Secretary of State Mike Pompeo downplaying the latest North Korean provocation since it did not involve an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of hitting the United States—and from President Trump hinting at tariff retaliation if a bilateral trade deal is not ready in six months—must have landed with a thud in Japan.

Indeed, President Trump had no qualms on the eve of his Japan trip to issue an executive proclamation identifying the gem of Japanese industry, the automobile sector, as a national security threat to the United States. It had long been suspected that the Commerce Department would yet again make a spurious case to the effect that imports (even from allied nations) impair the national interest, a case the executive branch can try to make under Section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act in order to justify the imposition of tariffs—as the administration did a year ago endorsing a “national security” tariff of 25% duty on steel and aluminum.

But the abuse of the national security rationale to cover for economic nationalism was more blatant this time. The Commerce Department’s report introduced a new distinction between foreign-owned and domestic-owned companies. It purported that a causal link exists between increased imports, lessened research and development resources in domestic-owned firms, and a compromised “ability to maintain technological superiority to meet defense requirements and cost-effective global power projection.” It is a sweeping conclusion, with the potential of jostling the world economy if tariffs were to materialize, and at the same time a completely opaque one, as the 232 report on autos has not been released to Congress or the public, precluding a thorough examination of its underlying assumptions, methodology, and empirical basis.

President Trump has moved the goal posts of U.S. trade policy in such dramatic ways that the executive proclamation on auto imports was met by many with a sigh of relief—relief that tariff action was delayed by half a year, and that this timeframe would push the decision point on a trade deal until after Japan’s Upper House election (this coming July), a key political constraint for Prime Minister Abe. While welcomed, these are short-term palliatives. President Trump has sent a most powerful message to Japanese (and all other foreign-brand) car companies: Their investments in the United States, irrespective of how many jobs they create and how much local economic activity they stimulate, will always be deemed second-class to those of domestic-owned firms.

In one fell swoop, President Trump has disarmed the charm strategy deployed by Prime Minister Abe to navigate tricky trade negotiations. To deflect pressure on the bilateral trade deficit, Prime Minister Abe has long tried to socialize President Trump to the transformation of the U.S.-Japan economic relationship resulting from the wave of Japanese investment in the United States over the last 30 years. Japan’s position as top foreign investor since Trump was inaugurated (with $20 billion and 37,000 jobs created) has been a recurrent talking point for the prime minister in his chats with President Trump, a point that the American leader cared to tweet to his followers. But now we know that President Trump will not change his mind, only reduction of automobile imports into the United States will do, either through a deal negotiated at fast clip or otherwise…

With his finger on the switch of national security tariffs, to be turned on and off as he pleases, President Trump is making the trading world safe for discrimination by exempting from punishment countries willing to go along with the precepts of “America First” policy, and discounting the contributions of foreign companies producing in the United States to favor domestic firms. No wonder Prime Minister Abe is keen to visit often with President Trump, if only to figure out what else he may have up his sleeve.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Mr. Trump goes to Tokyo: Behind all the pageantry, undercurrents of concern as tough trade talks loom ahead

May 24, 2019