Goldman Sachs has provided a lifeline to a desperate-for-money Venezuelan government by lending it $865 million in exchange for $2.8 billion in 2014 bonds (to mature in 2022) issued by Petroleos de Venezuela—the state-owned oil company. What might look like a terrific transaction for Goldman Sachs and its customers is in fact a disastrous deal, writes Dany Bahar, both on financial and—perhaps more importantly—moral grounds. This piece originally appeared in The Hill.

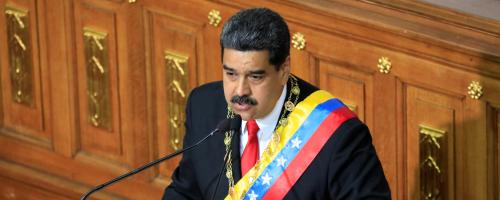

Just when the Venezuelan autocrat Nicolas Maduro was in need of help, Goldman Sachs came to the rescue.

Last week, we learned that Goldman Sachs provided a lifeline to a desperate-for-money Venezuelan government by lending it $865 million in exchange for $2.8 billion in 2014 bonds (to mature in 2022) issued by Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)—the state-owned oil company—and held until now by the Central Bank of Venezuela.

What might look like a terrific transaction for Goldman Sachs and its customers is in fact a disastrous deal, both on financial and—perhaps more importantly—moral grounds.

The ongoing street protests in Venezuela are fueled by a number of decisions taken by the government-controlled judiciary: First, in late 2016, it blocked a constitutional recall referendum that would have removed Maduro from power; and second, the Supreme Court nullified the National Assembly with opposition majority (a move denounced by the opposition as a coup d’état). This all happened during the worst humanitarian crisis seen in the continent in modern times.

The high levels of consumption—fueled by imports rather than production—during the past decade came to a stop after a sharp drop in the price of oil, Venezuela’s main and almost exclusive export. When foreign currency stopped flowing in, the country was too indebted to keep borrowing: Chávez, and later Maduro, had quintupled the country’s external debt.

Shortage of food, medicines, and basic goods became the norm. Since the crisis erupted, about 75 percent of Venezuelans have lost up to 20 pounds, and many have died from preventable diseases. Yet, there is only one thing that this Venezuelan government has been doing diligently—servicing its debt to foreign lenders. They know that defaulting will probably catalyze their departure from power.

Yet, undoubtedly, servicing the debt is becoming harder. Late last year, PDVSA struggled to convince its investors to join a debt swap with very generous conditions. The take-up rate was only 39 percent, and yet, PDVSA went on with the deal; probably an outcome borne of desperation. Still, many investors, including Goldman Sachs, see in PDVSA and Venezuela’s debt a worthy—though risky—investment.

The truth is that, even if investors remain somewhat myopic and overly optimistic, with Maduro in power, default might be unavoidable. PDVSA’s oil production dropped from over 3 million barrels per day (bpd) in the early 2000s to just about 2 million today, with the sharpest drop happening since Maduro took power in 2013.

With no cash flow, no properly-trained engineers or technicians left and with highly-corrupt management, PDVSA’s recovery—and thus ability to repay—is an uphill battle. With foreign reserves at the lowest levels of the past 15 years, the government cannot keep servicing its own debt nor come to the rescue of PDVSA.

Then there is the moral aspect of the Goldman Sachs investment. With this new line of credit, Goldman Sachs has chosen to keep financing a government that has transitioned to a fully-fledged dictatorship that has repressed its own people with military weaponry for the past 50 days. Over 40 civilians have died and hundreds have been injured as a result of brutality of the National Guard.

Thousands have been taken to prison and judged on the spot by military judges. The government has less than 20-percent popularity, and those in charge know they would lose any democratic election. Thus, Maduro is pushing for a new, everlasting and super-powerful Constitutional Assembly to change the constitution to allow him and his cohorts to remain in power forever.

In his proposal, he has shamelessly gerrymandered the electoral districts to be able to obtain an ample majority even with less than 20 percent of the vote. The opposition, along with many leaders in the continent and around the world have condemned this step and called for general elections as the only way to solve the ongoing crisis.

But as this happens, Venezuelans have vowed to remain in the streets. In spite of the repression, they vow to keep peacefully protesting until Maduro concedes on their demands: Free the hundreds of political prisoners, allow a humanitarian channel and hold long-overdue democratic elections.

Goldman Sachs, sadly, has put up a blind eye to this reality. As investors, they know the risk of losing their money by buying junk bonds, and it is all but guaranteed that they will. But as human beings, they should know better than to finance a corrupt, repressive, unpopular and dictatorial regime that is struggling to remain in power at any cost suffered by the Venezuelan people.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Goldman’s rescue of Venezuelan dictator is a moral and financial disaster

May 31, 2017