Earlier this month, the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff confirmed that Russia has violated the intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) treaty by deploying a banned ground-launched cruise missile. Such a missile poses a direct threat to Russia’s neighbors in Europe and Asia, but those countries have responded with virtual silence.

It may be too late to save the INF treaty, but the U.S. government should nevertheless try. Washington should seek to raise the political heat on the Kremlin by making the missile an issue between Russia and the countries that the missile will threaten.

The Russian treaty violation

Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the INF treaty in 1987, a landmark agreement that was the first to ban an entire class of nuclear weapons. The treaty prohibited the United States and Soviet Union (and now Russia) from testing or deploying ground-launched cruise or ballistic missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. By mid-1991, nearly 2,700 U.S. and Soviet missiles had been eliminated.

In 2014, however, the U.S. government formally charged that Russia had tested a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) of intermediate range in violation of the treaty. The Obama administration sought to persuade Moscow to return to full compliance, but the Kremlin apparently had other ideas. Washington says that Russia has now deployed the missile.

Republicans on Capitol Hill have responded by proposing, among other things, to build a U.S. intermediate-range, ground-launched cruise or ballistic missile.

Before taking such a step, the Trump administration should ask two questions. Can it afford those missiles in the Pentagon’s already-stretched budget? Moreover, would NATO members, Japan, or South Korea agree to deploy those missiles on their territory? Spending scarce defense dollars to build intermediate-range missiles to base in the United States—from where they would hold at risk targets in Canada and Central America, not Russia—makes little sense.

A security threat for Europe and Asia

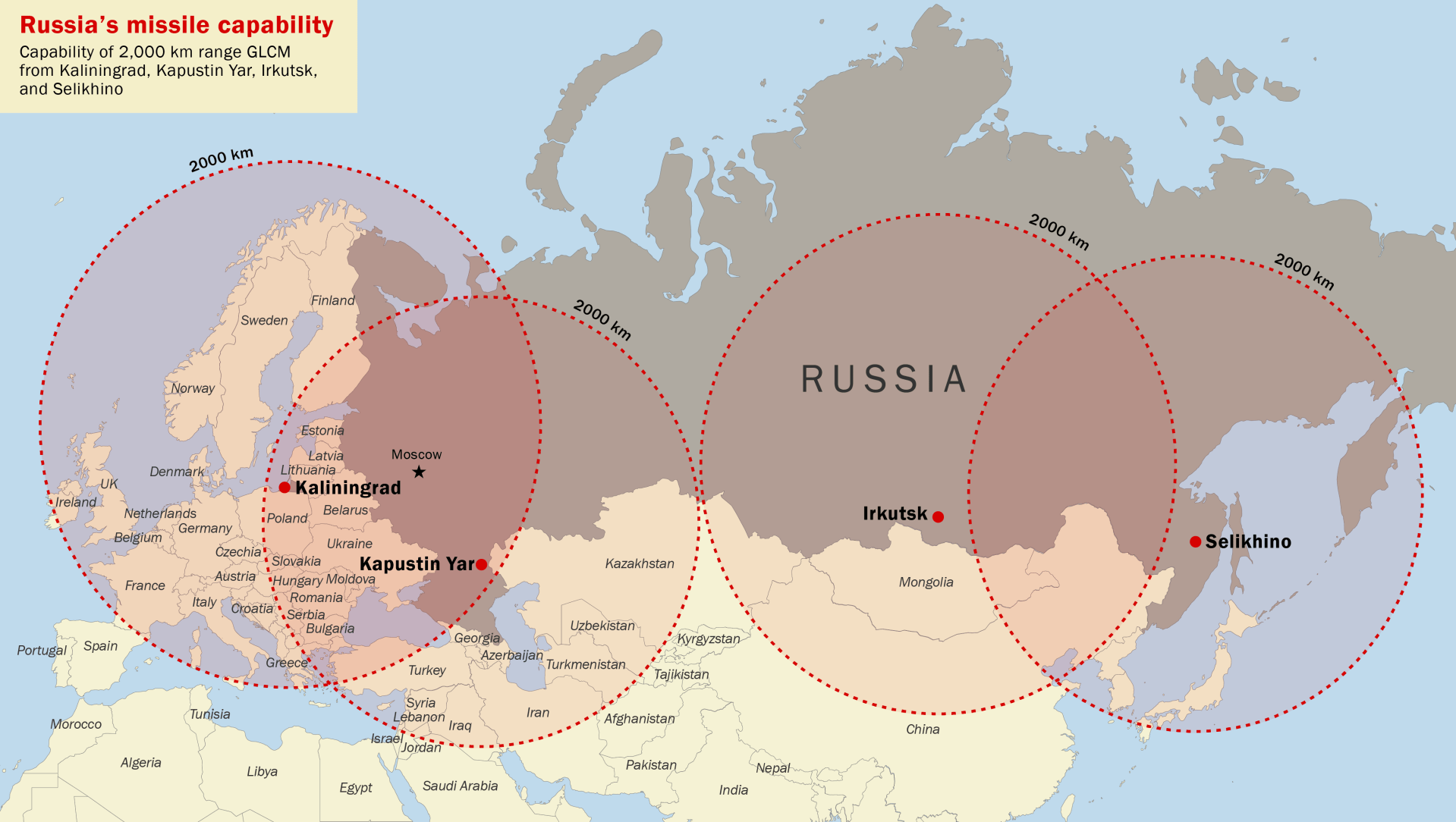

The range of the new Russian GLCM—reportedly designated the SSC-8—has not been made public, but assume it is 2,000 kilometers (about 1,200 miles). From bases in western Russia, nuclear-armed Russian SSC-8 GLCMs could target Helsinki, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Rome, Athens, Ankara, and even Paris and London. SSC-8s deployed in the Russian Far East could target Japan and South Korea, as well as much of China. The map below shows the reach of a 2,000-kilometer range GLCM from various locations in Russia.

The SSC-8 most likely could not reach American soil. (Alaska might be at some risk, but only if Russia deployed the GLCM in places where it has not deployed nuclear-armed missiles before.)

To be sure, this is a serious treaty issue between the United States and Russia. The primary security threat posed by the Russian missiles, however, is to Europe and Asia. Yet governments in those countries have voiced no real concerns, at least not publicly.

Part of the reason may be that the U.S. government has shared only limited information about the violation. It wishes to protect sensitive sources and methods.

That poses a problem. Two years ago, a senior allied official said privately that, while that official’s government believed the 2014 U.S. charge, the information provided was so scant that it would not publicly charge Moscow with a treaty violation.

Turning up the heat

The Trump administration should task the intelligence community with figuring out a way to share more details on the Russian violation with NATO allies, Japan, South Korea, friends such as Sweden and Finland, and countries such as China.

Washington should seek to multilateralize this question and turn up the political heat on Moscow. Given the current state of U.S.-Russian relations, it likely does not bother the Kremlin that the U.S. government is unhappy about the SSC-8 treaty violation. However, how would President Putin feel if he began hearing a stream of angry complaints from German Chancellor Merkel, Italian Prime Minister Gentiloni, Japanese Prime Minister Abe, Chinese President Xi, and other counterparts? Those countries ought to care, as they are the targets.

The INF treaty may well collapse. That would be a loss, particularly for nuclear security in Europe and Asia. To preserve the treaty—or to lay the basis for a cooperative international response—U.S. diplomacy should push other countries to engage on this question. The new Russian missile directly threatens them; Washington should get them into the game.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Multilateralize the INF problem

March 21, 2017