Europe’s management of its migrant crisis is abysmal. This is largely because the nation-state is inadequate to handle current geopolitical challenges. Put simply, individual European Union member states are unable to effectively handle migration flows on their own.

There are three overarching reasons for this. To begin with, managing migrant flows requires financial resources that most member states find difficult to mobilize. Secondly, migration is a topic that often stirs particularly conflicting perspectives across different domestic political environments. Finally, migrant movements present logistical challenges that individual countries can seldom effectively address.

Footing the bill

Most EU member states have to deal with shaky public finances. Between 2011 and 2014, the government deficit to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio of the EU as a whole shrank from -4.5 percent to -2.9 percent: getting better but still too high. Over the same period, the average government debt to GDP ratio for the 28 member states increased from 80.9 percent to 86.8 percent: soon to stabilize but still a drag on the economy on the long term. Meanwhile, and while gathering momentum from a puny 0.2 percent in 2013, GDP growth for the EU as a whole in 2014 was still a subdued 1.4 percent.

Moreover, the financial burden that comes with welcoming migrants is distributed too unevenly. Some countries are doing the heavy lifting in absolute terms: Germany’s readiness to take over 40,000 migrants in 2014 being a case in point. Other member states are displaying exceptional generosity by accepting very significant intakes relative to the total number of applications received—witness Sweden’s 74 percent recognition rate of refugee or subsidiary protection status in 2014. However, other member EU countries or other member states show little solidarity both toward their fellow EU member states and toward asylum seekers worldwide. Applications lodged in Hungary, Croatia, and Greece, for instance, are almost always rejected.

As is to be expected, states with weaker administrative and financial capacities struggle to cope with the recent migrant flows. Italy’s navy has for too long been left alone running its own operation Mare Nostrum—it is only now being supported by some fellow member states through Operation Triton. Greece is experiencing an ongoing economic, financial, and social crisis of historical proportions of its own. By the European Commission’s own admission, such a state of affairs has left the country unable to effectively police the EU’s southeastern external borders. A number of Western Balkan states, meanwhile, see growing diplomatic tensions emerge as they all become part of a broad transit corridor for tens of thousands of migrants attempting to reach Mitteleuropa.

Nationalism strikes back

Within an objectively challenging regional political context, xenophobic forces across Europe find fertile ground in their efforts to exacerbate the issue. In Helsinki, the Finns Party is effectively shaping policymaking: witness Finland’s abstention on the EU decision of September 22 to re-allocate asylum seekers currently in Italy and Greece. In a similar vein, the National Front keeps riding high in the polls in France, while the Danish People’s Party is ensuring Copenhagen does the very minimum when it comes to burden-sharing.

If xenophobic forces weren’t enough to poison the political debate, wildly differing starting positions make it very difficult for European governments to find common ground. Indeed, Europe so far had to deal with German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s “open doors” approach, with Hungary’s Viktor Orban’s religious-nationalist rhetoric, and with U.K. Prime Minister’s David Cameron usual awkward relationship with the rest of Europe. All this, while having to care for the views of all other member states.

The cultural background of some countries might also ease or complicate welcoming foreign migrants. Protecting Poland’s religious homogeneity, for instance, seems to be at the forefront of government policy when dealing with Europe’s migrant crisis. When dealing with asylum seekers, instead, Bulgaria too often fails to probe racist attacks on those individuals the country is supposed to protect. On a still more disturbing note, Slovakia has a poor track record of dealing with EU infringement proceedings for discrimination against its Roma minority.

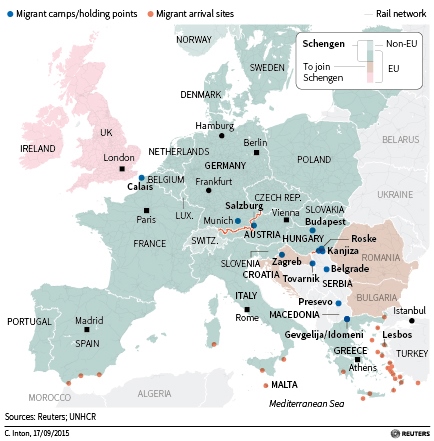

Map of the European Union showing the Schengen states and location of migrant camps or holding points. Credit: Reuters.

Borders that can’t be sealed

Within this context, migrant flows are logistically too challenging to be effectively managed by any single state. Ultimately, no member state is in a position to successfully absorb all the new arrivals to Europe.

Individual members can seal off their borders only at a significant cost. To begin with and from a merely logistical point of view, establishing border controls over 8,246 miles is no easy feat. Should border controls eventually be re-established across the Schengen area, inevitable delays and costs would immediately arise for intra-European trade in goods and services. In parallel developments, the freedom of movement enjoyed by European citizens within the area would also effectively come to an end.

Still from a logistical perspective, the evidence seems to suggest that no country could speedily and effectively process the expected arrivals. Indeed, Greece has all but given up processing them, while even mighty Germany is struggling with screening, registering, and welcoming the current influx. Even if individual member states were able to address these challenges, experience shows that migrant flows can rapidly move on to new routes, thus turning the efforts of a single country into an even greater challenge for another.

Beyond the nation-state

Even in a best-case scenario where all the above-mentioned challenges were to be adequately addressed, a supranational approach would still be necessary to facilitate the integration of migrants within European societies. As clearly highlighted by the Council of Europe itself, freedom of movement within the European Union’s borders, access to familiar socio-cultural networks and the matching of professional skills to labour needs across the continent would still be key to the successful absorption of foreign nationals within European societies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why Europe can’t handle the migration crisis

October 5, 2015