Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

The authors recently traveled to Erbil and Baghdad to conduct interviews with Iraqi officials, international actors from the U.S.-led coalition, and others on the ground.

A “yes” vote for single-issue referendums usually results in a myriad of unexpected consequences. In anticipation of such a “yes” vote in the forthcoming Kurdish independence referendum on September 25, there is unease among those tasked with post-ISIS stabilization in Mosul and Ninewah Province.

According to sources from direct interviews in Iraq, it is clear that concerns resonate not only in the Iraqi central government and among provincial officials, but also among U.S.-led coalition advisors who are currently playing a role in shaping and influencing Iraq’s post-ISIS security transition.

What Mosul brings to the anti-ISIS fight

Many senior security and political leaders in Ninewah Province have become impressed with their Kurdish counterparts in the past three years. One Ninewah-based senior Iraqi military figure we interviewed has gone as far as to suggest that the partner of choice in the fight against ISIS was located in Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), not Baghdad. Today, Baghdad offers only weak support—compared to the KRG for a Mosul-centric political, economic, security, and humanitarian approach.

Since the ISIS occupation of Mosul and Ninewah Province more broadly, many of the region’s leaders—particularly Sunni politicians and tribal sheikhs—looked east rather than south to Baghdad for support in counter-offensive planning and execution. The KRG offered sanctuary, and during the anti-ISIS offensive largely respected agreements pertaining to the role of Kurdish Peshmerga forces in re-taking Mosul. This has engendered respect from local Maslawis (people from Mosul) and their leadership in the post-ISIS stabilization phase.

Security cooperation

Among senior security and military personnel in Mosul and Ninewah, there is, however, a significant and growing sense of apprehension that Kurd-Arab cooperation would be upended if the referendum passes. There is already evidence that the modalities of security cooperation between state security forces in Mosul and Kurdish-controlled checkpoints are under strain, as evidenced by increased scrutiny of once-routine logistical and security patrols to places like Makmour. This includes patrols that are directly supporting the coalition itself. For this reason alone, Mosul-based Iraqi political and security leaders emphasize the importance of a continued presence of coalition advisors and assistance. Local Iraqi commanders on the ground have acknowledged that the presence of American coordination mechanisms has helped repair relationships between local forces when they have broken down.

Some senior coalition advisors located in Mosul echo such concerns. They see the lack of international support for the upcoming Kurdish referendum as fueling the Kurd-Arab security dilemma that is developing in the evolving post-ISIS landscape. This is a landscape, particularly in areas of East Mosul, where Kurdish input is still valued—and indeed necessary—in the management and delicate maneuvering required among a variety of state and non-state armed elements.

Referendum politics

Many of Ninewah Province’s highest-ranking political officials are unwilling publicly to express a view on the merits or otherwise of the Kurdish referendum in and of itself. However, they do acknowledge that “yes” has implications for the consolidation of hard-won gains in the region in this delicate post-ISIS stabilization phase. This inevitably has consequences for confidence in partnership building among pre-existing governance structures such as the Mosul-based Ninewah Provincial Council (NPC). The NPC governor Nofal Hammadi al-Sultan presides over a multi-ethnic and sectarian governing forum that has actively partnered with local and international security actors in the current stabilization phase.

A “yes” vote gives rise to understandable concerns with respect to the NPC’s current role and the fate of its elected Kurdish members. In the 2013 NPC election, the electoral alliance between the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) delivered them 11 seats and majority bloc status. Moreover, in late August this year the NPC agreed to allow Kurdish voters living in Ninewah (including those living within PMF controlled areas) to participate in the Independence Referendum.

From a local perspective, it is important to remember that East Mosul is where most of the city’s Kurdish residents have long made their homes. Political elites and locals alike have substantial cause for concern if there is a “yes” vote from East Mosul’s Kurdish residents. There are some Kurdish leaders who still uphold their prior claims and influences over the city, and consequently, there are fears among state and non-state elements in Mosul that Kurdish plans for the territorial annexation of eastern Mosul and areas of Ninewah could be revived and lead to ethno-sectarian clashes when they are least needed. The internal dynamics between the KDP and their rivals in the PUK, especially in areas south of Mosul where the PUK enjoys territorial sway, only complicates the security challenges here.

Inherent Resolve?

Because of the ethnosectarian make-up of the province and its history as an ISIS stronghold, achieving sustainable stability in Mosul and Ninewah Province more broadly is critical for the success of the U.S.-led coalition’s mission of destroying ISIS. The potential for a loss of focus on countering ISIS here is increasing as the referendum draws nearer. This, in turn, only increases the likelihood of a reemergence of takrifi-jihadi recruiting in the province.

The international community should continue to work to delay this referendum until the political and security realities in the region are more conducive. Today, a strong argument can be made that anti-ISIS efforts trump Kurdish desires for self-determination in the short term, particularly because a resurgence of ISIS in the region would decrease the likelihood of actualizing these desires in the long term. Recent parliamentary votes in Baghdad and Erbil, however, suggest that agreement on a delay is unlikely. Accordingly, the U.S.-led coalition should begin taking steps now in anticipation of a 25 September “yes” vote.

Senior political leaders in Erbil, Baghdad, and Washington have all vocally supported an enduring U.S. military advisory mission in the context of ongoing negotiations over a status of forces agreement between the United States and Iraq. With political consensus between Erbil, Baghdad, and Washington around the necessity for an enduring U.S. presence in Iraq as a starting point, the U.S.-led coalition is uniquely situated to mitigate the risk of Kurd-Arab conflict that has the potential to derail the gains made in the anti-ISIS campaign thus far.

To do so, the coalition should first clearly communicate its commitment to preventing the outbreak of sectarian conflict, particularly between Iraqi security forces and the Kurdish Peshmerga. This commitment could then be reinforced at the tactical level with “presence patrols” conducted by coalition forces in areas of elevated ethnic tension. In light of recent declarations by Prime Minister Abadi authorizing the use of force by the Iraqi Army in response to any political violence stemming from the referendum, partnered patrols with the Iraqi Army would be particularly helpful. Reports of ethnosectarian violence should not be ignored. Rather, coalition forces should seek to actively de-escalate tensions by moving to points of friction, not away from them.

The coalition should seek to facilitate coordination mechanisms between the Government of Iraq (GoI) and the Kurdish Regional Government. For example, coalition advisors could facilitate the emplacement of Peshmerga liaison officers in the Ninewah Operations Command to help de-escalate tensions between the Iraqi Army and the Peshmerga. In the longer term, the coalition should look to the possibility of re-instituting coordination methods like the Combined Security Mechanisms used between 2009 and 2011 that were useful in physically preventing the unintended outbreak of conflict along the KDL and in disputed areas. Further, coalition advise-and-assist commanders should build advisory relationships with leaders in the NPC to maintain better situational awareness about shifting GoI-KRG political disputes that could have direct security impacts on the province and in Mosul. This could help identify ethnosectarian tensions “left-of-bang” and focus advise-and-assist efforts in potential trouble spots at the local level that might not be visible to coalition advisors in Erbil, Mosul, and Baghdad today.

Using the forces it already has postured in Iraq, the U.S.-led coalition can use the capital it has built up in Iraq throughout its counter-ISIS campaign to mitigate the growing Kurd-Arab security dilemma, consolidate gains, and prevent Kurd-Arab political unrest from metastasizing into a broader conflagration that would likely undo much of the security progress made to date.

Alexander Brammer is a Ph.D. candidate at Queen’s University Belfast and is currently serving as an Infantry officer in the United States Army. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense or its components.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

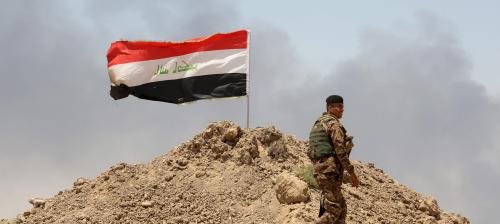

Mosul eyes Kurdish referendum

September 20, 2017