Many governments, including several important U.S. allies, simultaneously fight and encourage the terrorist groups on their soil. This two-faced approach holds considerable appeal for some governments, but it hugely complicates U.S. counterterrorism efforts—and the United States shouldn’t just live with it. This post originally appeared on Lawfare.

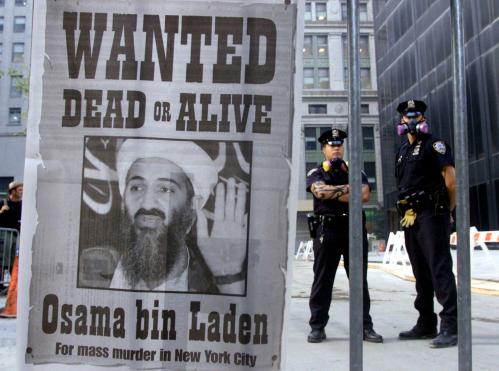

Not all countries that suffer from terrorism are innocent victims doing their best to fight back. Many governments, including several important U.S. allies, simultaneously fight and encourage the terrorist groups on their soil. President George W. Bush famously asked governments world-wide after 9/11 whether they were with us or with the terrorists; these rulers answer, “Yes.”

Some governments—including at times Russia, Egypt, Turkey, and Pakistan among others—hope to have it both ways. They use the presence of terrorists to win sympathy abroad and discredit peaceful foes at home, even while fighting back vigorously enough to look plausible but not forcefully enough to solve the problem. This two-faced approach holds considerable appeal for some governments, but it hugely complicates U.S. counterterrorism efforts—and the U.S. shouldn’t just live with it.

We’re not talking about straightforward state sponsors of terrorism like Iran, which brazenly supports Hezbollah and others, or basket-case quasi-states like Somalia, whose government is too feeble to provide basic services, let alone defeat a rampaging terrorist group like al-Shabaab. Here we’re talking about governments that are at least semi-competent and notionally oppose the terrorists, yet still think it’s in their interests to give militants some rope or even tacitly aid them.

These governments come in various shades of democracy and autocracy, but they all put their international ambitions or domestic politics above sustained counterterrorism. As these leaders see it, the presence of terrorists among their foes discredits the entire opposition—including peaceful groups.

Consider Syria, where, in the first days of the 2011 rebellion against the longtime Assad dictatorship, the regime released key jihadists from prison even as it jailed thousands of peaceful pro-democracy protesters. Assad and his cronies decided they would rather fight small numbers of jihadists than a mass movement of nonviolent democrats—and set busily about choosing their own opposition. The regime has focused its military operations on pummeling moderate opposition groups and, at times, colluded with the Islamic State. The more Assad tars his opposition with the brush of Islamist extremism, the more his brutal regime can plausibly claim that it is fighting a “war on terrorism.”

Similarly, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has long used the presence of international jihadists in the breakaway region of Chechnya to reject nationalist Chechens’ demands for independence. After 9/11, Moscow has tried—rather successfully—to rebrand the Chechen cause as a jihadist front tied to the U.S. war on terrorism.

Embattled regimes can also use the presence of jihadists in their opposition to try to win over wavering middle-class supporters and key minority groups. In Egypt, jihadist violence in the 1990s made the middle class more willing to accept the sclerotic, repressive Mubarak government. Two decades later, the junta led by Abdel Fattah el Sisi is attempting to link all of its opponents—including the millions who backed the elected Muslim Brotherhood government he overthrew in 2013—to the country’s nasty jihadist problem in Sinai. The jihadists represent a small fraction of the country’s Islamist opposition, but Sisi uses their presence to legitimate the most draconian crackdown in modern Egypt.

In Syria, the country’s Christians, Druze and other religious minorities were initially sympathetic to the 2011 protests against Assad. But as the jihadists have grown more vicious and dominant, the regime has tried to rebrand itself as the champion of those fearing repression if the country’s Sunni majority comes to power by force. Minorities, reluctantly, are turning to Assad out of self-defense.

Some governments seek to channel jihadists against the regime’s enemies. The regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen exploited jihadists returning from the anti-Soviet struggle in Afghanistan to subdue the Yemeni socialist regime in the south during the country’s civil war. Turkey tolerated the flow of fighters to Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaida affiliate in Syria, and allowed the group to operate without interference on Turkish soil because the group was an effective adversary against Turkey’s enemy, the Assad regime. Pakistan has done this most consistently, working with groups like Lashkar-e Taiba to fight India and secure Pakistan’s interests in Afghanistan.

The United States and other countries often reward leaders facing a jihadist problem. The Algerian regime had become a pariah in the early 1990s after the military regime aborted democratic elections because Islamists were winning. When Algerian terrorism struck France in 1995 and 1996—terrorism possibly manipulated by the Algerian regime itself—France and other countries came to see the regime as the lesser of two evils. Over time, France provided military and intelligence support to the Algerian regime, and the United States came to view it as an ally against al-Qaida. Similarly, since 9/11, the United States has given Pakistan more than $2 billion in aid a year, much of it in the name of counterterrorism, even though much of the country’s jihadist problem is of the regime’s own making.

Governments that tolerate terrorism put regime security ahead of the security of their citizens.

Governments that tolerate terrorism put regime security ahead of the security of their citizens. Too much violence weakens and discredits the regime, but a limited amount can go a long way. Car bombs in the marketplace or attacks on their own religious minorities are tolerable sacrifices to bear in order to justify the regime’s grip on power or bolster its international position.

The counterterrorism consequences, however, can be disastrous. Even though these regimes seek to keep a lid on the violence, it regularly boils over. Yemen’s supposedly tame terrorists would later embrace al-Qaida and nearly down several U.S. airliners. Pakistan’s proxies would turn on the Pakistani state itself, leading to near-civil war in which tens of thousands of Pakistanis have died. Algerian jihadists form the core of an al-Qaida affiliate that is active in Libya, Mali, Mauretania, Tunisia, and other countries in the region.

For the United States, it is difficult to distinguish friends from enemies. Algerian support is vital to fighting al-Qaida in the Maghreb, but the regime’s policies contributed to the problem. Pakistan exemplifies this dilemma more than any other country. Islamabad has proven essential in the many U.S. successes against the al-Qaida core. At the same time, Pakistan’s ties to militant groups have helped the Taliban and other radical groups flourish, destabilizing the regime and contributing to the deaths of hundreds of Americans in Afghanistan.

Squaring counterterrorism with other U.S. policy goals is the biggest challenge. The Egyptian regime’s deliberate conflation of its jihadists and the Muslim Brotherhood opposition makes it hard for the United States to aid Egyptian intelligence and military forces against the Islamic State province in Sinai without improving Cairo’s ability to crack down on more peaceful opposition forces. As the Sisi and other regimes intended, the United States needs them for counterterrorism and so it will overlook their other sins, including their exploitation of their country’s jihadist problem.

U.S. silence on these issues is expedient for day-to-day cooperation, but over the long-term it enables regional regimes to lie to their people and the world to the detriment of both counterterrorism and overall U.S. interests. More open and candid criticism would ruffle feathers, but it would also lay down a marker and make it harder for these regimes to play a two-faced game.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A convenient terrorism threat

September 20, 2016