While employment continued to rise, today’s employment report suggests that the pace of job growth slowed. Employer payrolls increased only by 115,000 jobs, following a gain of 154,000 last month and average increases of 252,000 per month in the three prior months. At last month’s pace of job growth, increases in employment are roughly keeping up with increases in new labor market entrants and the unemployment rate was little changed at 8.1 percent.

U.S. immigration policy continues to be a key issue of debate among federal and state policymakers alike. In that debate, one area of disagreement has been the impact of immigration on the U.S. labor force and the wages of American workers—particularly during today’s difficult economic times. In fact, because of the weak labor market immigration flows have changed dramatically since the start of the Great Recession—the undocumented population has declined (Passel and Cohn 2010; DHS 2012), and the number of high-skilled H-1B visas being issued was down by over 25 percent in 2010 from a 2001 peak (US State Department). As the economy continues to recover, however, it is likely that demand for immigrant labor by American businesses and the desire of immigrants to work in the United States will continue to rise. The ability of our immigration system to respond to these demands remains an important economic policy issue, both in the short term and for our country’s long-term growth strategy.

In this month’s employment analysis, we discuss the economic evidence on what immigration means for U.S. jobs and the economy in advance of The Hamilton Project’s May 15th immigration forum in Washington, DC. We also continue to update our analysis of the “jobs gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels, releasing an exciting new interactive feature that allows readers to calculate when the country will close the jobs gap at different rates of job creation.

The Impact of Immigrants on Employment and Earnings

Although many are concerned that immigrants compete against Americans for jobs, the most recent economic evidence suggests that, on average, immigrant workers increase the opportunities and incomes of Americans. Based on a survey of the academic literature, economists do not tend to find that immigrants cause any sizeable decrease in wages and employment of U.S.-born citizens (Card 2005), and instead may raise wages and lower prices in the aggregate (Ottaviano and Peri 2008; Ottaviano and Peri 2010; Cortes 2008). One reason for this effect is that immigrants and U.S.-born workers generally do not compete for the same jobs; instead, many immigrants complement the work of U.S. employees and increase their productivity. For example, low-skilled immigrant laborers allow U.S.-born farmers, contractors, and craftsmen to expand agricultural production or to build more homes—thereby expanding employment possibilities and incomes for U.S. workers. Another way in which immigrants help U.S. workers is that businesses adjust to new immigrants by opening stores, restaurants, or production facilities to take advantage of the added supply of workers; more workers translate into more business.

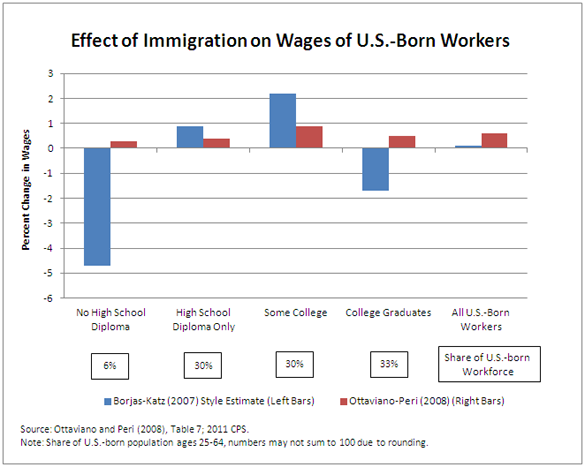

Because of these factors, economists have found that immigrants slightly raise the average wages of all U.S.-born workers. As illustrated by the right-most set of bars in the chart below, estimates from opposite ends of the academic literature arrive at this same conclusion, and point to small but positive wage gains of between 0.1 and 0.6 percent for American workers.

But while immigration improves living standards on average, the economic literature is divided about whether immigration reduces wages for certain groups of workers. In particular, some estimates suggest that immigration has reduced the wages of low-skilled workers and college graduates. This research, shown by the blue bars in the chart above, implies that the influx of immigrant workers from 1990 to 2006 reduced the wages of low-skilled workers by 4.7 percent and college graduates by 1.7 percent. However, other estimates that examine immigration within a different economic framework (the red bars in the chart) find that immigration raises the wages of all U.S. workers—regardless of the immigrants’ level of education.

A Path Forward with An Economic Approach to Immigration Reform

Our current immigration system has myriad challenges: dozens of overlapping visa categories—each with different quotas, costs, and durations—characterize the system of legal immigration, supplemented by country-specific caps, and even a randomized visa lottery. As a result, the system is plagued by problems, ranging from its cumbersome and costly application systems, to its inefficient ability to meet the needs of American families and an ever-changing economy. One measure of the inefficiency is the thousands of dollars in legal fees that many visa applicants must spend.

In a forthcoming discussion paper for The Hamilton Project, “Immigration Policies for Jobs, Productivity, and Growth,” University of California, Davis, Professor Giovanni Peri puts forward one approach to immigration reform that focuses on addressing economic concerns about the U.S. immigration system. Peri’s proposal has several steps, ranging from reforms of the current system to a wholesale restructuring. The first step of his proposal is to introduce a market-based auction system to allocate existing temporary employment visas. Rather than waiting in line to bring a worker into the country as an employer would do in the current system, employers would bid on a permit to sponsor that worker in an auction. Revenues from the auctions could be used to run the system and to compensate the state and local governments that have the largest fiscal burdens from immigration. The discussion paper, which will be released on May 15, details the other steps and reforms.

The April Jobs Gap

The Hamilton Project continues its monthly analysis of how the “jobs gap” has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007. This month, the Hamilton Project updates its jobs blog analysis with a new interactive feature that allows readers to calculate how long the jobs gap will take to close under different rates of job creation. This interactive feature is available by clicking here.

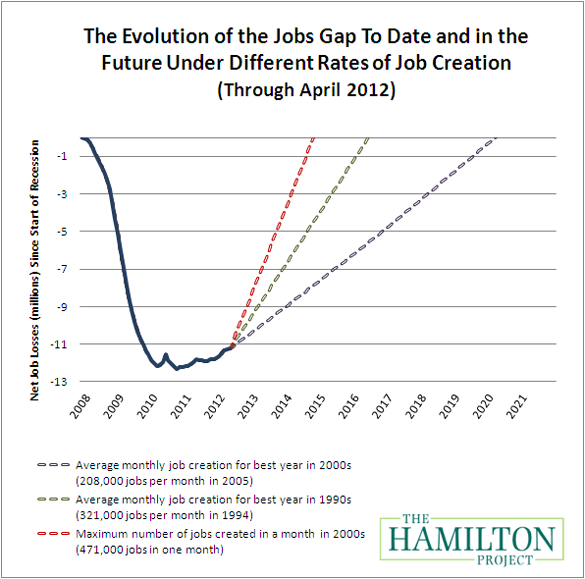

As of April, our nation faces a jobs gap of 11.2 million jobs. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the jobs gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until March 2020—or eight years—to close the jobs gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by June 2016—not for another four years. To see how long the jobs gap will take to close at other rates of job creation, click here.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the economic recovery has been slow and many American workers remain unemployed. Amidst concerns about how immigrants affect the labor market and economic activity, immigration remains a hotly debated issue by policymakers, but it is necessary to ground the debate in facts. This was the impetus for The Hamilton Project’s 2010 document, Ten Economic Facts About Immigration.

On May 15, The Hamilton Project will continue to explore the challenges and opportunities for immigration reform in today’s political and economic climate. In addition to a panel discussion around Giovanni Peri’s new proposal, a roundtable of thought leaders will discuss many of the broader issues surrounding today’s immigration reform debate, including former U.S. Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE), Silver Lake Co-Founder Glenn Hutchins, National Council of La Raza President and CEO Janet Murguía, and UNITE HERE President John Wilhelm. For more information or to register for the event, click here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What Immigration Means For U.S. Employment and Wages

May 4, 2012