The NCAA basketball tournament is one of the most-viewed sporting events in the United States. In 2019, nearly 20 million viewers watched the championship game, and each tournament game (67 total) averaged about 10 million viewers. Over 17 million people completed a March Madness tournament bracket for the 68-team tournament. Among youth, basketball is one of the most-played and most racially diverse sports. The NBA does well too. In fact, a racial breakdown shows that the NBA is the most racially diverse major U.S. sport.

Though overtly racist incidents are not uncommon in basketball, they are often actively punished in the public sphere. The late Don Imus was fired in 2007 for referring to members of the Rutgers University women’s basketball team as “nappy-headed hos.” Former LA Clippers Owner Donald Sterling was banned from all NBA activities and fined $2.5 million after he was recorded making racist comments in 2014. And the NBA stood behind its players when they wore “I Can’t Breathe” shirts in solidarity with Black Lives Matter activists protesting police brutality in 2014. Basketball seems to be a bit ahead on the fronts of equity and inclusion.

Public focus on and condemnation of overtly racist incidents is consistent with the common belief that sports promote racial egalitarianism, but it may leave the dubious impression that racial bias is otherwise absent from these spaces. Published recently in the American Journal of Sociology, our analysis of in-game commentary of over 10 years of NCAA men’s college basketball games challenges this idea. We aimed to determine whether the skin tone of players impacts how commentators discuss their in-game play and abilities.

To conduct our study, we collected data from a random selection of 54 games from NCAA basketball tournament games from 2000-2010, including the championship game in each year. By watching video broadcasts, transcribing the audio of in-game announcers, and coding every comment made about every player in the games, we sorted the nearly 2,700 comments into categories related to performance, physical characteristics, and mental characteristics of the players.

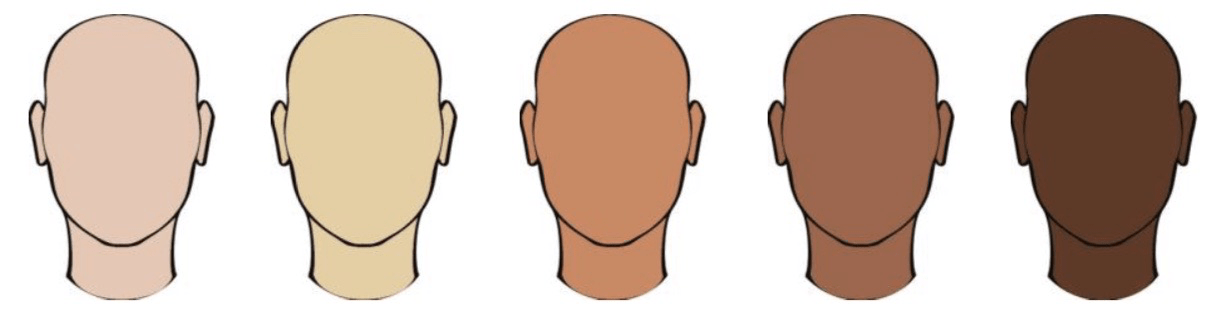

To compare the commentary to the skin tones of the players, we collected pictures of each of the over 400 players from basketball rosters and university websites. Next, we tasked over 2,000 respondents to evaluate the skin tone and race of each player using a skin-tone scale and racial categories. We categorized players into five main skin-tone quintiles (as shown in the graph below).

Finally, we analyzed the data, taking into account players’ skin tone, race, tournament variables, and players’ objective performance to determine what factors explain how announcers talk about players during games. What quickly became clear is that stereotypes about skin tone and race play a significant role in how announcers describe players during games.

Lighter-skinned players were more likely to be described for their performance (e.g., shooting, rebounding, steals) and mental abilities (craftiness, cleverness, control). Cleverness, craftiness, and control were often discussed in terms of strategic thinking. An example coded as cleverness included “Clever. Really understands the game,” while examples coded as craftiness included “We’ve talked about [M.H.] and how crafty he is. [S.] is much the same way as a perimeter player—knows how to use that height at 6’5” very effectively to get into the lane.” Comments about control included “He’s the horse whisperer is what he is. Anybody that can tame horses can definitely control opponents on the basketball.”

“[S]tereotypes about skin tone and race play a significant role in how announcers describe players during games.”

Darker-skinned players were more likely to be described for their physical characteristics (e.g., athleticism, speed, strength). Announcers focused on the size and height of darker-skinned players even though lighter-skinned players were taller and weighed more. Likewise, lighter-skinned players were discussed more for rebounding despite darker-skinned players having more rebounds per game.

The implications of darker-skinned players being stereotyped as more physical and athletic compared to lighter-skinned players has far-reaching ramifications. Racial bias is potentially problematic for both lighter-skinned and darker-skinned players. On one hand, the intellect of darker-skinned players may be overlooked due to stereotypes about their bodies. On the other hand, lighter-skinned players may be negatively evaluated for the NBA draft if their physical abilities are downplayed in favor of assumptions about work ethic and mental ability. NBA teams are looking for players with upside, not players who have allegedly maxed out their physical skills in college.

There were a few exceptions to these general patterns. Jumping ability, specifically, was associated more with lighter skin tones. It could be that seeing lighter-skinned players jump high counters stereotypes and becomes more salient as a result. Darker-skinned players were associated with having more “awareness.” Although awareness seems to imply intellectual acuity, the comments we coded as representative of awareness highlighted reactivity and the ability to pay attention and focus. Reactivity is often framed as instinctual or inherent rather than intellectual. For example, in reference to one player, an announcer commented, “He does a good job of tracing the ball—we call it—tracing the ball with your eyes and with your hands.”

“Stereotypes about Black intellectual inferiority and white physical inferiority continue to manifest in 21st-century America.”

Stereotypes about Black intellectual inferiority and white physical inferiority continue to manifest in 21st-century America. Our analysis suggests that sports are not immune from the manifestations of racism and may, in fact, play a vital role in shaping beliefs and interpretations about intellectual ability, physical ability, and performance more broadly.

For example, racial stereotypes about the physical inferiority of lighter-skinned individuals may lead some to believe that sports are primarily suited for darker-skinned people. Implicit biases in sports may also impact other social institutions. This could occur in the classroom, where teachers use racial stereotypes about the intellect of darker-skinned students and their (in)ability to be crafty or clever in school. Or it may happen in the community, where neighbors may use racial stereotypes about criminality when they see a darker-skinned individual walking down the street.

We should note that our findings are not necessarily about individual announcers. We took into account the skin tone of announcers and still found similar results. Instead, we believe that our findings speak to the broader culture and structure of collegiate athletes and in-game commentating.

While announcers often say whatever comes into their minds as they are watching a game unfold, they are also typically provided scripts about each player that they build upon. These scripts, often written by sports journalists and other media staffers, rely upon information about players that is normally provided by the team’s own front office or players themselves during interviews. The lack of racial diversity in these positions may foster a culture embedded with racial biases that comes to the surface in the form of stereotypical comments about the physical and intellectual abilities of players.

Stephen Bardo—president of the Chicago chapter of the National Basketball Retired Players Association, sports commentator, and host of Everyone Loves Food and Sports—agrees:

“[T]he findings [are] in line with what happens when commentating a game. Everyone has biases they use to interpret the world around them. Calling college basketball games is no different. I do believe more Black administrators, coaches, and commentators can bring a richer, more informed experience to college basketball.”

Based on our analysis, we recommend that athletic and media organizations commit to improving the racial diversity of collegiate coaches, upper-level athletic staff, journalists, and media support staff who decide what content about players will be broadcast. Relative to the percentage of non-white collegiate players, non-white upper-level administrators were under-represented by about 300% in 2018. In 2017, 87% of all Division-I head coaches were white. Creating a more racially inclusive culture in these organizations can go a long way toward improving the coverage of athletes and their performances.

“Creating a more racially inclusive culture in these organizations can go a long way toward improving the coverage of athletes and their performances.”

As multiracialism increases in the U.S. and racial classification becomes more ambiguous, skin tone may be a major factor that people use to make sense of their social worlds, whether it’s about how they view a basketball player on a televised game, students at their children’s school, teenagers walking down the street, or colleagues at work. It is imperative that organizations and companies, such as the NCAA, do more to recognize racial bias, understand how it permeates their decision-making processes, and then work toward building a more equitable future for athletes, fans, and society at large.

Commentary

March Madness and college basketball’s racial bias problem

March 6, 2020