As economies grow from low- to middle-income and countries improve health outcomes, they are expected to transition away from health aid—external sources of health sector funding. It is a complex and challenging process. If mismanaged, the potential for backsliding (i.e., disease resurgence and reversal of health gains) is sizeable.

To help middle-income countries manage their transitions to domestically funded health systems, in recent years, various transition readiness assessment tools (TRAs) have been developed. TRAs can be used to determine: (1) whether a country is ready to graduate from donor support; (2) how transition will affect various aspects of the health, economic, and political system of the country; (3) where donor funds may need to be spent to bring a country closer to being transition-ready; and (4) whether the country’s progress will be sustained after transition from donor aid.

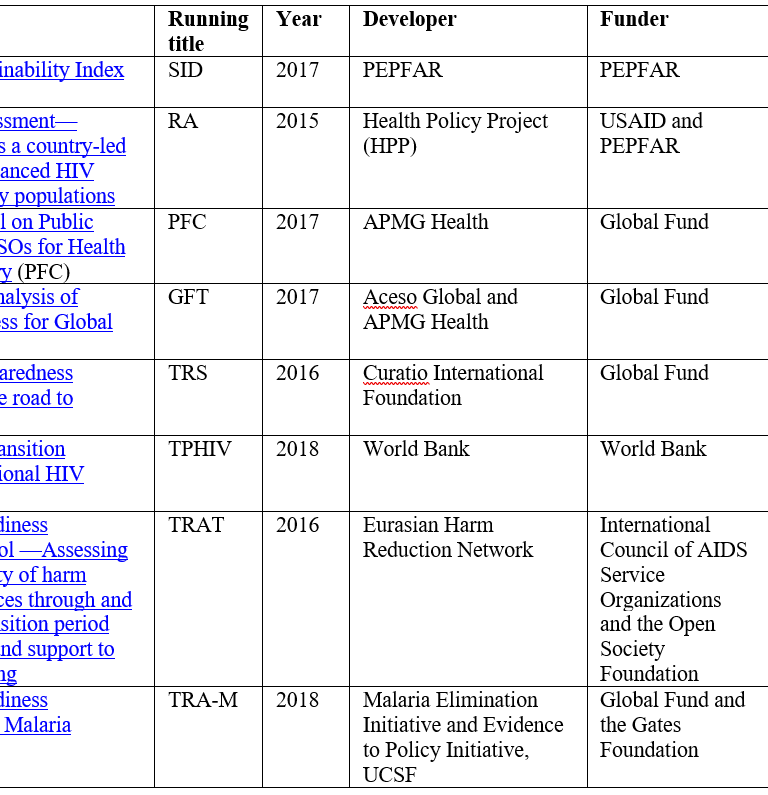

To understand the benefits and limitations of TRAs, we analyzed existing tools to provide insight into the current landscape of TRAs and opportunities for guiding transition planning and supporting the sustainability of health programs and systems (Table 1).

Table 1. Basic description of TRAs included in our analysis

Note: Publication year indicates the year the most recent version of the tool was released.

Note: Publication year indicates the year the most recent version of the tool was released.

What we found

All eight health-sector TRAs were introduced after 2015, suggesting that there is growing demand for transition planning support and assessment instruments. TRAs have helped the transition planning and preparedness process in several ways:

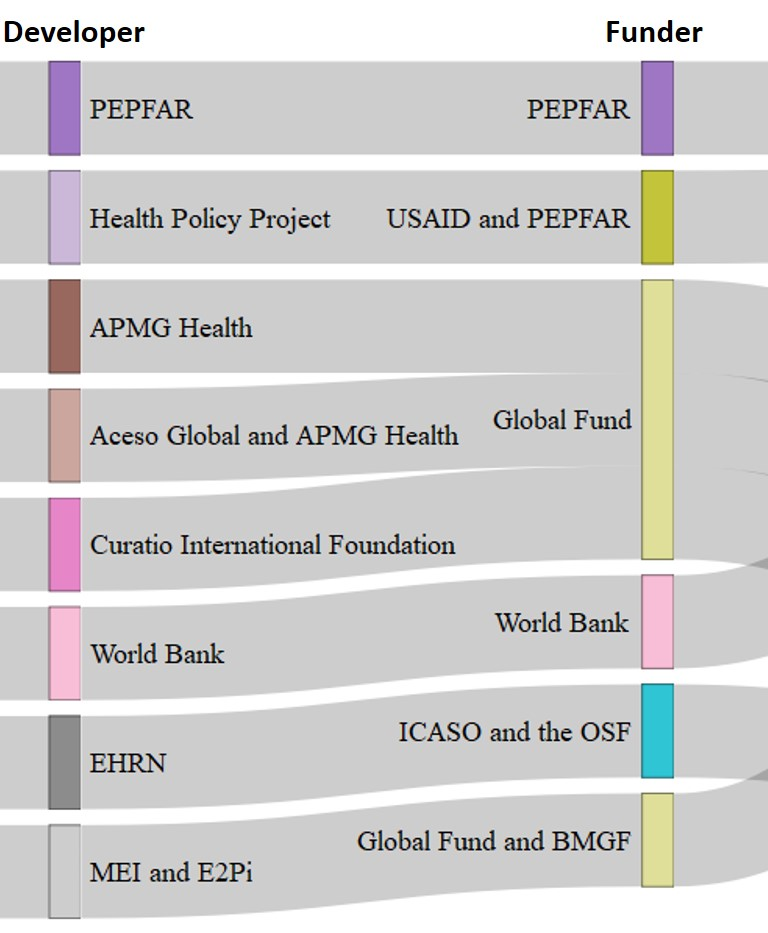

- Current TRAs focus on three high burden infectious diseases that continue to threaten global health progress: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. This aligns with the priorities of key funders of the TRAs: the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and the Global Fund (Figure 1).

- Most TRAs are intended to be used by countries for improved transition planning, despite having a range of purposes and being primarily donor-driven. Participation of in-country stakeholders is specifically mentioned in several TRA reports.

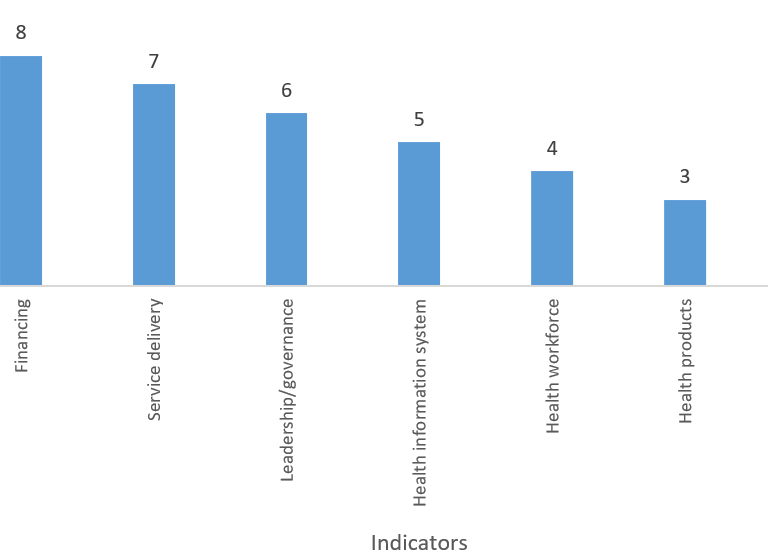

- TRAs address multisectoral factors in the indicators measured. All six components of the health system have been measured by one or more TRAs (Figure 2). Additionally, most TRAs measure factors beyond the health sector, such as policy/legal environments, monitoring and evaluation, and CSO contracting capacity.

- TRA assessments are not one-size-fits-all; they use various approaches to collect and analyze data inputs. While quantitative data has the advantage and potential to be compared or tracked for different years and among different countries, qualitative information can be used to identify gaps/barriers that are not clearly measured by quantitative data. The diverse approaches used by TRAs enable countries to choose TRAs based on the availability and quality of data in their countries.

- TRAs have been tested and redesigned. Although transition is a relatively new phenomenon, developers of several TRAs have already tested their approach in countries as pilots, using feedback to improve their design.

Figure 1. Funders, developers, and diseases targeted by TRAs

Source: Transitioning from Health Aid: A Scoping Review of Transition Readiness Assessment Tools

Figure 2. Frequency of indicators and measurements used by TRAs to assess transition readiness

Source: Transitioning from Health Aid: A Scoping Review of Transition Readiness Assessment Tools

We also found some limitations in existing TRA tools:

- There is considerable overlap between tools as well as clear gaps. All eight TRAs focus on the same three diseases. Current tools do not help countries transition from external funding for any other disease control programs (e.g., vaccination and maternal and child health programs) or for broader health systems strengthening.

- TRAs do not consider the emerging challenges faced by transitioning countries, such as demographic changes (e.g., aging of populations and a bulge in the adolescent band of the population pyramid), epidemiological transition, or multiple donor transitions.

- Donors are the financial and technical “drivers” of all TRAs. All existing TRAs were either developed or commissioned by donor organizations. Even though TRAs aim to assist recipient countries, countries’ demand for TRAs is unclear. If countries’ voices are not reflected in the need for the development of a TRA, it is hard to conclude whether or not the TRAs as designed will address the country’s most critical needs in transition planning.

- Even though most of the TRAs were intended to be used by in-country stakeholders, the role of in-country stakeholders is not clearly defined. Most TRA documents state that in-country stakeholder engagement is encouraged, yet provide limited information on which stakeholders are required for the assessment and their suggested roles.

- Many TRAs have not made their manuals or guidelines publicly available, thereby potentially limiting their usefulness to users. Even for TRAs that have published their manuals or guidelines, the description of methods typically lacks clarity and details. This missing information could be a barrier for countries in using the TRA to conduct a transition readiness assessment. The problem is particularly acute for TRAs that use a scoring system as their output. For the same reason, we believe it is hard for potential users (e.g., country stakeholders) to follow the published TRA reports and conduct the assessment without seeking help from the TRA developer.

Making transitions better

There are clear opportunities for improving existing TRAs including recommendations for the development of new tools designed to address some of the critical gaps previously mentioned.

- Coordination is essential for new TRA development in order to prevent overlap, build upon existing TRAs, and address gaps in transition planning.

- Understanding and incorporating countries’ needs and demands in the design of new TRAs will be critical.

- More consideration and focus is needed on how to make TRA results more applicable for countries in transition planning. A tool that addresses countries’ demands and needs in transition management and encourages collaborations across in-country stakeholders would have many benefits, including but not limited to “buy-in” from in-country stakeholders on the results from a TRA.

- Policies and initiatives should be implemented that address concerns and harness the opportunities of transition planning when gaps and opportunities are identified in the use of TRAs.

- A platform of lessons learned across countries that have conducted TRAs should be developed for knowledge sharing, best practices, and addressing emerging challenges.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Do transition readiness assessment tools inform donor transitions in health care?

April 30, 2021