Today, Iraq stands between the distant promise of peace and the reality of ongoing war. The defeat of the Islamic State in Mosul in July 2017 paved the way for reconstruction. With Mosul free from Islamic State control, the burden of security on Iraq’s budget is likely to grow. But by how much?

The answer depends on how soldiers and diplomats determine risks and threats; how Iraqis and their international partners enact strategies to counteract them; and on how economists and public finance experts cost the financial implications of security strategies in addition to the many other expenditures of reconstruction. Mosul’s infrastructure costs alone could rise to $1 billion, as the conflict has shattered about three-quarters of roads, almost all of the city’s bridges, and 65 percent of its electrical network.

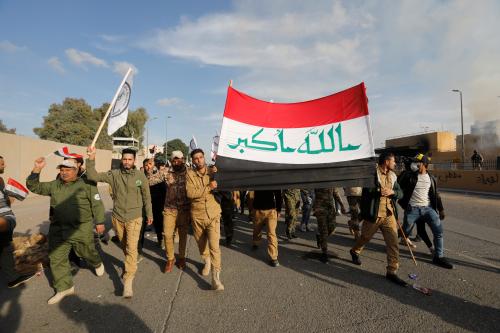

And as the smoke clears in Mosul, tensions rise in Kurdistan. In late September, the regional government in Erbil organized a referendum to declare independence. On October 16, Iraqi forces took control of Kirkuk, an oil rich city that Kurdish Peshmerga fighters had seized from the Islamic State in 2014. Meanwhile, the central government has called for a national partnership with the Kurds within a unified Iraq.

Between rebuilding Mosul and maintaining the peace with the Kurds, economic growth and equitable development can boom only if Iraq remains free from endemic violence. This requirement is based on at least two conditions: (1) the costs of providing security and justice services in a free Mosul are affordable; and (2) Baghdad and Erbil work out a framework that sustains cooperation between Kurdish and Iraqi forces.

The costs of defense, policing, and courts are already high. In 2014, the World Bank estimated that defense, public order, and safety (including police, courts, and prisons) together accounted for 16 percent of Iraq’s total expenditure or 9.2 percent of GDP. Of the share allocated for employee compensation in the 2012 national budget, the Ministry of Interior ranked first, with 25.6 percent, whereas the Ministry of Defense ranked third, with 11.7 percent (education was second with 21 percent, and health was fourth with 8 percent).

As objectives shift from active fighting toward maintaining public order, the role of policing will become more prominent. This puts a heavier burden on personnel and maintenance costs rather than capital, and thus a significant premium on ensuring that officers are paid on time and in full.

Moreover, an enduring partnership between Iraqis and Kurds will need both economic and security guarantees. The equitable distribution of oil revenues between Baghdad and Erbil will remain essential to stability. Yet, without a framework for cooperation between Iraqi and Kurdish forces, peace will become elusive. One way to prevent this outcome is to anchor politically sensitive discussions in raw data and realistic assessments of economic and financial needs of public safety and defense. This could be accomplished through a review of public expenditure in security and justice across the whole of Iraq. This assessment should cover Iraqi and Kurdish security institutional arrangements and their financial dimensions as a technical input to a national political dialogue.

Development practitioners naturally focus on social service delivery and natural resource management as key ingredients of post-conflict reconstruction. But neglecting the costs of security—and its related public financial management infrastructure—will undermine Iraq’s reconstruction and recovery. Afghanistan serves as a case in point. In 2005, a public expenditure analysis determined that Afghanistan’s security sector needed $1.3 billion per year, or 23 percent of GDP, with over 75 percent financed by donors. Afghan security spending exceeded domestic revenues by over 500 percent. By 2010, nearly 40 percent of core on-budget spending (operating and development) was allocated to security, while education received 15 percent, infrastructure just 14 percent, and health a mere 4 percent.

Today’s Iraq can benefit from the lessons of the past. As shown by the Afghan case, one such lesson is to treat the security sector as a critical public sector entity, subject to the same rules of affordability, efficiency, effectiveness, and transparency. For this to happen, economists should seek to partner with unlikely companions—the soldiers and the diplomats.

Paul M. Bisca is a conflict and security specialist currently on assignment with the World Bank’s State and Peacebuilding Fund. He is the co-editor of “Securing Development: Public Finance and the Security Sector,” a joint U.N.-World Bank study published in April 2017.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Stabilizing Iraq: A job for soldiers, diplomats, and economists

October 30, 2017