The conventional wisdom about the American economy is that, in spite of the recovery, middle-class Americans are still hurting. Moreover, the conventional wisdom is that the decline in middle-class fortunes has been going on for decades. But a new Brookings paper from the economist Rob Shapiro upends the conventional wisdom, offering a more accurate look into what’s been happening to Americans and their pocketbooks.

Shapiro does this by taking advantage of new Census Bureau statistics which report household income by age. There are significant advantages to looking at earnings by age instead of in the aggregate. For instance, the conventional measure of aggregate median income covers all households from the teen years to 64. So it captures millions of people who are still in school and millions who are partially or totally retired. The measure is, as Shapiro points out, a messy one, which changes over time thus making it hard to see what’s really going on.

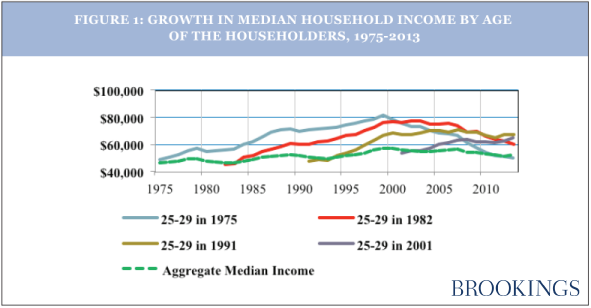

The advantage of looking at income by age cohorts is that, as we all know, incomes rise as we age and get more education and experience and then they tend to level off or decrease as we get older. And so, looking at incomes by age cohort gives us a very different picture than it does when everyone is lumped together. For instance, as Figure 1 shows, aggregate income from 1975 to the present looks pretty flat. But people who were 25-29 in 1975 experienced pretty healthy gains in their incomes as they aged, as did young people in 1982 and 1991.

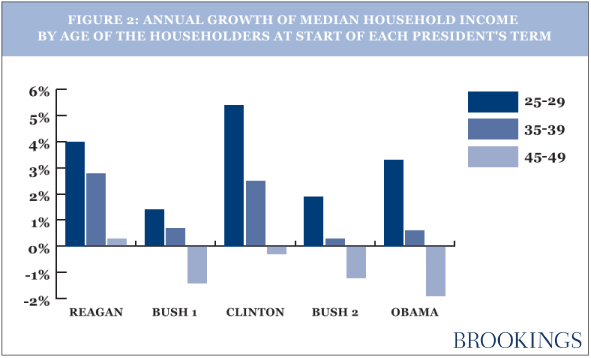

Shapiro then looks at income growth by age for the past five presidents and finds that the “…largest average annual gains in median household income occurred during the Clinton and Reagan administrations, with a clear edge to Clinton.” As figure 2 illustrates, young people in the Reagan and Clinton years saw their incomes grow right into middle age. The contrast with the Bush and Obama years is stark. Under those two presidencies income growth is lower for young people, small for those entering middle age and negative for those in the 45-49 year age group. No wonder our recent politics has been so bitter. As William Galston notes in another Brookings paper, “Economic stagnation means a continuation of gridlocked, zero-sum politics and a turn away from the spirit of generosity that only a people confident of its future can sustain.”

In other words, this can’t continue.

Shapiro concludes that “our current problems with incomes are neither a long-term feature of the U.S. economy nor merely an after-effect of the 2008-2009 financial upheaval.” Nor are they driven by “economic impediments based on gender, race and ethnicity, or even education.” He identifies two structural causes; globalization and information technologies. But he also asks us to think about what Reagan and Clinton did that the two presidents of the 21st century did not do. “The Clinton and Reagan fiscal approaches supported stronger rates of business investment than seen under Bush-2 or Obama. In addition, their support for aggregate demand included public investments to modernize infrastructure, broaden access to education and support basic research and development.”

This paper should be studied by all who want to be president in 2016. It presents a balanced look between those who argue that our problems with incomes are all structural and therefore we can’t do much about them and those who argue that they are all the result of policy decisions made by individual presidents.

Commentary

Household income growth under four American presidents

March 6, 2015