This is the third piece in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills, including problem solving, metacognition, critical thinking, and collaboration, in classrooms.

Metacognition is thinking about thinking. It is an increasingly useful mechanism to enhance student learning, both for immediate outcomes and for helping students to understand their own learning processes. So metacognition is a broad concept that refers to the knowledge and thought processes regarding one’s own learning. Importantly, there is research evidence (e.g., Moely and colleagues, 1995; Schraw, 1998) that metacognition is a teachable skill that is central to other skills sets such as problem solving, decisionmaking, and critical thinking. Reflective thinking, as a component of metacognition, is the ability to reflect critically on learning experiences and processes in order to inform future progress.

David Owen, who teaches history and politics at Melbourne High School in Victoria, Australia, discusses a simple but effective approach to encourage student self-reflection:

I have rethought some of my classroom strategies this year. I teach at a secondary school which prides itself on its high level of student achievement, and I had always believed my students performed accordingly. They always ask for help before, during, and after class. Their varied queries could be superficial knowledge-based questions or more general questions about their progress, but I’d always read this habit as a sign that my students had an open mindset: they were inquisitive, cared about their learning, and charted their progress.

But having students asking a million questions of the teacher poses another challenge entirely, which can be framed: “Why aren’t students asking these questions of themselves?”

Recent shifts in pedagogy have emphasized the importance of encouraging students to figure out how to be independent, self-regulated learners. The teacher cannot be there to hold their hand beyond school. This demands that students reflect on their learning in meaningful ways. It also requires students be critical analysts of their own thinking in order to overcome complex or unexpected problems.

I’ve begun to highlight strategies which might better encourage this kind of metacognition. For younger adolescents, I’ve found that “Exit Tickets” are an opportunity for students to reflect on what they have accomplished and what they could improve on. Exit Tickets are a family of feedback tools that students complete for a few minutes at the end of each lesson. They prompt students to think about how and what they learn, as well as what challenges they are still facing.

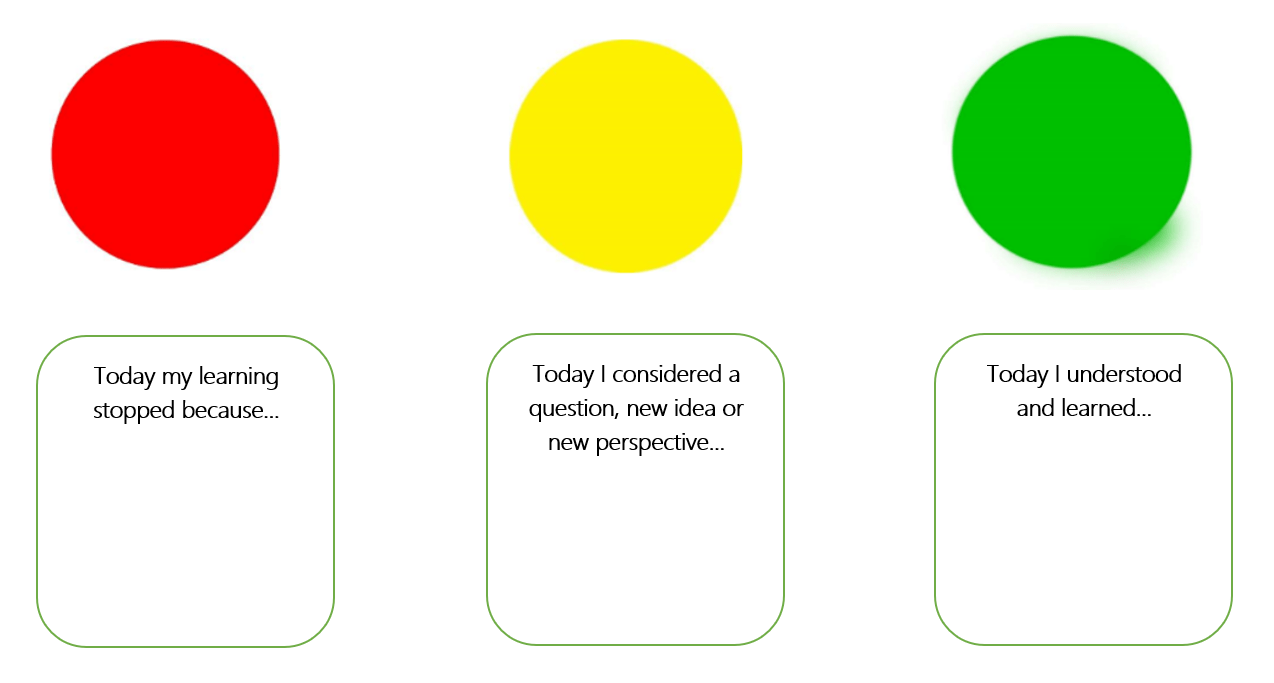

“Traffic Lights” is a simple yet effective Exit Ticket which emphasizes three key factors:

- When students encountered a challenge;

- When students had thought differently about something; and

- When students were learning well.

Over time I’ve found myself more interested in student responses to the Yellow Light, because it requires students to think about how they were thinking, rather than when (the emphasis of the Red and Green lights). The Yellow Light encourages reflective thinking as well as “thinking about thinking, or what is known as metacognition.” The possibilities for Exit Tickets are numerous and easily adaptable to the content and specific skills taught in any lesson.

Another example of reflective, self-directed learning which is suited to group work is setting a classroom rule that groups ask a question together, rather than individually. What this means is that rather than immediately ask the teacher for help, a student who has encountered a problem must consult with their group first. If the group cannot collectively find the solution, they can raise their hands simultaneously—a sign that the question has been fielded to the group already. There are various ways to modify this rule: highlighting with traffic-light colors, like in the Exit Ticket activity, is one such example.

For older students, setting a few rules before requesting aid from the teacher has seen their self-directed learning—and my feedback—improve markedly. I have emphasized that students seek specific feedback concerning their trial exams. I ask students to ensure they have highlighted and annotated their responses before seeing me. This approach shifts student thinking from the simplistic “submission to feedback” principle towards a more involved process, where students must consider what feedback they would want, what advice they would give themselves, and where they think they need to improve. This approach encourages the students to independently exercise control over their learning and progress, thereby making them more independent and self-directed learners.

Evidence supporting the impact of metacognition suggests that students applying metacognitive strategies to learning tasks outperform those who do not (Mason, Boldrin & Ariasi, 2010; Dignath & Buettner, 2008). The classroom approaches that David Owen uses in his classroom demonstrates one way of developing parts of this important complex skill. Interestingly, although these skills are so important in our modern world, the approaches discussed here are practical, do not require 21st century technology or resources, and can be applied in almost any classroom setting.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Strategies for teaching metacognition in classrooms

November 15, 2017