When he introduces himself, Dzingai Mutumbuka modestly says he’s had a few jobs in education, including teaching in two universities and the World Bank. What you come to learn later is that he has also spent more than a decade as a minister of education. First, he worked during the civil war in white-ruled Rhodesia, ensuring children from bush communities could continue their education in neighboring Mozambique while the country fought to overthrow the minority government. After independence, Mutumbuka was named the first minister of education of newly formed Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1988. He assumed the post of minister of higher education from 1988 to 1989.

As we continue to study examples of learning interventions from around the world, and if and how they can be best scaled up—our Millions Learning Project—I had the chance to sit with Dzingai to get his insights, informed by both international and local experience, on how we can help to productively shape education policy.

Jenny Perlman Robinson: As a former policymaker, what kind of information do you think is most influential in motivating reform?

Dzingai Mutumbuka: Generally, if a policy is not grounded in rigorous analysis and also in practice, that particular policy is likely to be problematic. We know that too often, governments announce policies without any serious analysis of their implications.

And, in almost every case, we have seen serious problems. I can give you a couple of examples: when universal primary education was the flavor of the month, the government of Uganda decided to provide UPE. However on realizing the overall cost they backtracked, saying they are going to provide free primary education for the first four children in the family. Which begs the question: what if I have five, seven or eight children? Does it mean that my other children cannot be provided for? In another instance, in Lesotho, they implemented free primary education by announcing, “from a certain date all students will get free primary education.” Guess what the rational parents did? They made their children repeat first grade so they could get free education.

So what I’m saying is that policy must be grounded in facts, and it must be based on analysis of the reality on the ground. I don’t think that you can say that given the importance of context, all evidence should only be domestic; or given how interconnected the world is today, all evidence should be international. It should come every source that you can get your hands on.

For example, in Zimbabwe we did not have enough infrastructure, and yet we wanted to expand secondary education fast. We decided to use a double-shift system where one group of students and their teachers have school in the morning, and the other group in the afternoon or early evening. We looked around and we found out that Hong Kong and Singapore had been practicing this approach for decades with success. At the same time, we also decided to use local experience. Unlike Hong Kong or Singapore—they are like city states—local experience informed us that most of our students were in rural areas. In these sparsely populated areas, there was not sufficient population density to implement the double-shift method effectively. So, we decided that double-shift policy would apply mainly in urban areas. In this case, international experience informed by local context shaped the policy.

JPR: In many instances of national reforms, there’s been a high-level champion behind its success. How do you balance this against the need to ensure that the reform lasts beyond the champion’s time in office?

DM: In one sense, I’m a very good example of this; in another sense I’m a very bad example. The good part is that when I was minister of education, I stayed for long enough to see my reforms through a whole cycle of the system. Because I was minister of education for 10 years it meant that, since primary education is seven years, I could see an entire cohort of students go through the whole cycle of the primary school and evaluate the results. Similarly, since the secondary education cycle was six years, I could see the reforms and even change them if necessary. It also meant that I had to eat my own cake because if a reform didn’t work, I had no one else to blame but myself. So, that’s the good part.

The bad part is that typically in Africa, very weak politicians are appointed as ministers of education. By weak, I mean those with low political clout. Or sometimes the president decides he will punish you by appointing you as minister of health or education—there are thought to be so many problems in those ministries that the minister will drown in the challenges.

In contrast we can look at successful reforms in the United Kingdom by Margaret Thatcher while she was minister of education. This means you need a strong person, a strong woman especially, to be able to implement successful reforms. The last thing you need is a weak minister. That’s exactly the wrong signal. When you have people who are strong like the Iron Lady, you are likely to succeed. I would say that, in summary, to implement successful reforms in education, you really need someone with political clout and they should stay long enough to see at least one cycle go through—tenure is important.

JPR: What do you think are a few upcoming hot issues in scaling innovations in learning? As we build on these conversations with Millions Learning, what do you see as the frontier issues?

DM: That’s a difficult question. The solutions are not easy or obvious. I think that the problem with education is that it is so easy to focus only on one aspect of education. For example, there has been a lot of focus on access or on infrastructure. We know that access without learning is a waste of scarce resources. And we know that infrastructure takes a lot of money. But we need to ask what really is education?

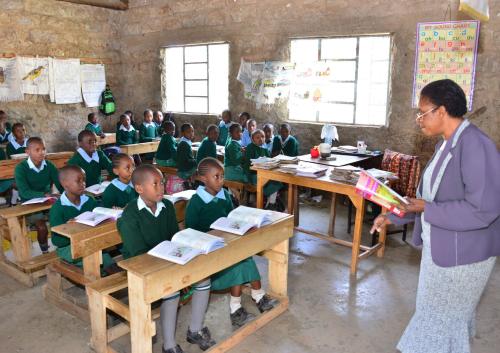

We should really think of education as a marketplace where students and teachers meet, for the purpose of teaching and learning. If we start thinking in those terms perhaps we will concentrate on what really matters; we will concentrate on teachers being able to teach effectively, doing what they’re supposed to do. We will also concentrate on teachers helping students to learn, whether sometimes that’s providing nutrition, deworming, whatever it takes, we should focus on creating the best marketplace where teaching and learning actually take place.

During our struggle for freedom, we used to run schools for over 12,000 students in Mozambique. We did not have a single building. Education was a marketplace. Teachers focused on what matters: making sure that students learn. The students focused on making sure that they learned. Whether this was under a nice tree—it didn’t matter. So, the focus needs to be how we produce an efficient marketplace where the process of learning and teaching takes place efficiently. We need to come up with innovative ways to make sure that children learn.

JPR: Do you think that technology has a role to play in innovation in education and learning?

DM: Absolutely. But I would say to you, innovation is first and foremost about ideas. Technology is simply a supplement. What we need are the best ideas. Yes, technology can play a catalytic role, but let’s not overemphasize technology. The mission is what should drive our focus. The other day, I saw a person sitting on the metro opposite me, and she had a t-shirt with a very simple caption “all children can learn.” Just think about what it means—it’s meaning runs very deep. The things that you need to do in education are probably not very complicated, not even technologically sophisticated. You just need to think innovatively. You can pick ideas from others, but you always have to apply the parameters to the local context.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Implementing National Education Reforms: Learning from International Experience While Informed by Local Context

January 21, 2015