An estimated 700,000 Syrian refugees have poured into Turkey since the start of the Syrian war. Many refugees have benefited from Turkey’s “temporary protection” policy and have received services ranging from food and shelter to education in camps along the border. However, as the conflict has intensified, far greater numbers of Syrians populate makeshift camps or reside in host communities. This has important ramifications for education: The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that of the one million Syrians that will reside in Turkey in 2014, 795,000 will be children, half-a-million of whom will be of school-going age.

The Turkish response to the Syrian refugee crisis is led by the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD) and is characterized by services provided in camps and services provided to non-camp refugees. In camps, the government partners with UNHCR and UNICEF to provide educational services. Many Syrian children have lost between one and three years of education. In 2012 and 2013, only 60 percent of primary school-aged boys and girls in Turkish camps were enrolled in school. Additionally, UNHCR reports that there are some vocational training courses, language courses, or extra-curricular activities offered in Turkish camps.

While there is still more to be done in camps, non-camp services are also critical. Many more children are residing in host communities than in camps in Turkey. In 2014, UNHCR expects 159,000 children to reside in camps, compared to 636,000 in host communities. Despite the size of this population in need, only 14 percent of primary school aged children outside of camps are enrolled in school in Turkey. Outside of camps, families struggle to find free schools that offer Arabic language instruction for Syrian children. In the cases where Turkish schools offer an afternoon shift for Syrian refugees, transportation can also be a barrier. When schools are available, they more often cater for primary school years.

In Gaziantep, an industrial city in South Turkey, I visited the Friendship II School for Syrian refugees. This school was founded in 2013 for grades five through eight (Friendship I was founded in 2012 for grades one through four). The mayor of Gaziantep saw the need to serve the large influx of refugees and so granted the plot of land that the school sits on as well as five buses that bring children from surrounding areas. A successful Turkish businessman donated the building, playground, soccer field and basketball courts in honor of his mother, a former teacher. The waiting list for this school is growing, even as the mayor searches for land for another school: 75 girls and 90 boys are on the list, with hundreds more families lining up to put their names down.

A Syrian refugee at the Friendship II school studies English. A Syrian refugee at the Friendship II school studies English. |

The 645 students that attend this school come for morning or afternoon classes and the teachers work a double shift for which they receive a small bonus and a free lunch. The school director is Syrian, from Aleppo, the teachers are Syrian and the curriculum is Syrian, although all references to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad have been removed. Brimming classes of 5th and 6th graders welcomed me in simple English and asked for peace and help for Syria. I entered the 7th grade boys’ class and the school director pointed out that by this year, half of the boys are missing from the class as they are out working to help sustain their families. |

The prevalence of child labor among Syrian refugees, particularly for boys, has been noted in the region by UNHCR, which works to combat this issue. Children work to buy food and to pay rent for their families, many of whom fled with the clothes they were wearing and the few things they could carry.

|

In Kilis, a city near the Syrian border, I went to a school run by Kimse Yok Mu (which means Isn’t There Anybody Who Can Help Me?) for Syrian refugee children in grades one through four. Kimse Yok Mu is a humanitarian non-profit that operates schools in Syrian border cities, including one that I visited where the municipality of Kilis pays the rent on the facility. In this school, Syrian teachers are volunteering their time, as the organization has not yet secured funding for salaries. The children are learning in co-educational classrooms that offer both a morning and an afternoon shift. In Kilis, the organization runs five schools and reaches 2,500 children. |

Many boys are absent at the Friendship II School. |

In some families, children are the only ones who can work. Parents may be absent, disabled or injured as a result of the war. In some female-headed households, it is culturally unacceptable for mothers to work and the burden can fall to boys. In other cases, older men cannot get employment doing menial tasks or cannot withstand the shame and abuse associated with the jobs available to youth.

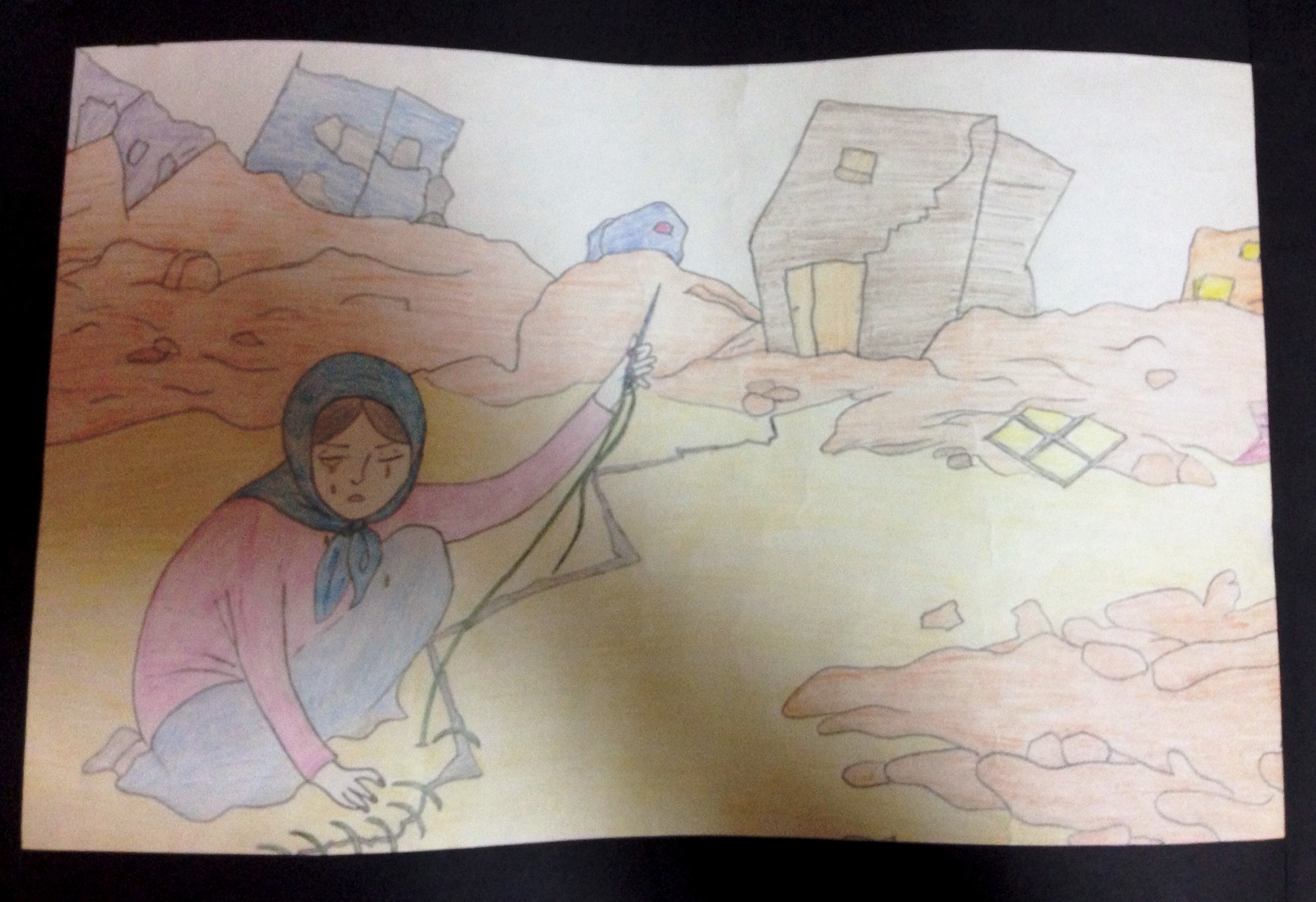

The curriculum used is the same as in Syria, with the same exam structure, although the children are learning Turkish. The organization aspires to expand services so that no Syrian child should miss any years of education. During the school’s “morale night” one of the students drew the picture below.

|

|

Five Priorities for Non-Camp Children in TurkeyThe Turkish government and partners within Turkey are offering a range of educational services to Syrian refugees. The Turkish response is reaching a greater proportion of children than the response in either Lebanon or in Jordan, the two other countries that shoulder the lion’s share of refugees from the Syrian war. In Turkey, the following actions can support the effort to respond to the Syrian refugee population with education services: |

|

A Syrian refugee drew this picture during a morale night. Other pictures featured tanks, fires, bombing, bloody casualties, tents at refugee camps and dreams of playgrounds. A Syrian refugee drew this picture during a morale night. Other pictures featured tanks, fires, bombing, bloody casualties, tents at refugee camps and dreams of playgrounds. |

2. Offer targeted programs for male youth. Regional reports show evidence of high rates of child labor among male adolescents. In order to help these young boys so that they may continue their education, civic organizations should be encouraged to offer targeted programming. Conditional cash transfers can offer an incentive for families to keep both boys and girls in school.

3. Focus on post-primary education as well. Little is known about the enrollment rates among post-primary school age Syrian refugees in non-camp settings in Turkey. Yet education at this stage is critical for this generation’s future prospects and for their protection as they mature into adulthood. In 2010, 93 percent of male youth and 91 percent of female youth in Syria were enrolled in lower secondary education—more research is needed to understand the impact of the war on the educational prospects of these youth.

4. Fund and conduct more research on non-camp populations. The children in the non-camp population are hard to reach and at times hard to number. The fortunate ones are studying, but many more are at home or dispersed in cities and towns. Little research and evidence is available on these children and youth in Turkey. Further study of these populations should inform the response including study of Syrian’s settlement in non-border cities.

5. Expand international partnerships. The Turkish Government has played a critical role in leading the response for Syrian refugees. Yet, more international partnership is needed in order to meet the growing demand for protection and services. The Turkish Government and the international community should explore various ways to ramp up partnership, including support of local organizations that can support non-camp populations over the long term.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Education for Syrian Refugees in Turkey – Beyond Camps

January 17, 2014