Not long ago, the SADC Tribunal, the Tribunal of the Southern African Development Community, was a proud landmark in the pristine Windhoek cityscape in Namibia. Much hope was vested in the court, whose mission was to effectively and efficiently ensure compliance and resolve disputes related to the interpretation and application of SADC treaty and subsidiary legal instruments.

Through this mandate, the court also both directly and indirectly supports sustainable and equitable economic growth and socio-economic development and promote deeper cooperation among SADC’s 15 member countries.

The SADC Tribunal was created in 1992, at which time many wanted the tribunal’s mission to extend beyond questions of economic cooperation into the realm of human rights protection, much like the ECOWAS[1] Community Court of Justice. Africa-wide civil society and academia agree upon the need for citizens to be able to resort to a regional tribunal when their domestic legal systems fail to provide relief. Indeed, the first president of the tribunal called the institution a “House of Justice for Africa.”

Now, though, when one comes across the white colonial building with the words “SADC Tribunal” stamped in bold black letters, one will no longer find that promising institution. Stripped of its once grand purpose, the building is now used as an ordinary domestic court.

Not all hope is lost: A recent ruling in South Africa indicates that the SADC Tribunal might be revived. With this revival can come a new strong impetus to hold SADC governments accountable for human rights violations, show regional solidarity on the importance of human rights, and, as a consequence, promote economic prosperity.

The Zimbabwe land-grabbing case

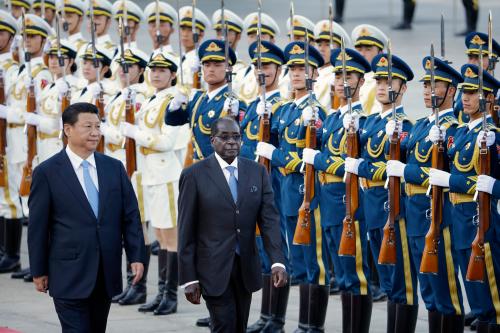

The SADC Tribunal barely got off the ground when it died a slow death as the result of political interference by Zimbabwe in 2007-2008. The first and the last case heard by the tribunal—the Mike Campbell case—involved 79 white Zimbabwean commercial farmers who took the Mugabe government to the court to stop the compulsory acquisition of their farms. The tribunal found for the farmers on the basis that they were deprived of their land without the right of access to the courts and the right to a fair hearing, both of which are essential human rights. In this way, the tribunal held that the Zimbabwean government breached the provisions in the SADC Treaty.

Notably, the case has implications beyond the direct ruling and for economic growth and development: By defending the rights of these farmers, the court also protected their economic freedom and property rights—ideas critical to promoting investment and growth, and thus economic success.

The political fallout was immediate. The Zimbabwean government refused to enforce the judgment, and the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe decided that its government has an inherent right to compulsorily acquire property. The decision of the court seems to have trumped the SADC Tribunal’s decision: As a direct result of the Zimbabwean opposition to the Campbell decision, the heads of state and government of SADC decided to suspend the tribunal until August 2012. Then, in August 2012, the doors of the tribunal closed to individuals. Since the court was primarily set up to hear individual cases, this meant that it effectively came to a standstill.

Many believe that the disbanding of the SADC Tribunal in 2012 was reflective of SADC’s hierarchy of values in which the organization’s formal commitment to human rights and a regional legal order is subordinate to the political imperatives of regime solidarity and respect for national sovereignty. Whereas states have traditionally been very willing to relinquish sovereignty with regard to direct trade and economic matters, human rights have remained a sensitive and neglected issue. The case further showed a lack of appreciation for the idea that the decisions of regional courts could take priority over national courts.

The importance of regional courts and hints of the tribunal’s resurrection

The future of the rule of law, economic freedom, and human rights protection in Africa might depend on the willingness of African states collectively to defer sovereignty to regional courts. Since many African citizens are subjected to violations like arbitrary detention, unfair trials, and unlawful deprivation of property without recourse to domestic courts, the SADC Tribunal could provide a forum and legal remedy should their domestic court systems fail them. There are good reasons why the African Court of Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR), the only African regional court, does not fill this gap. Because of the significant procedural obstacles individuals face in approaching the ACHPR, citizens of SADC countries only had the SADC Tribunal to turn to for a remedy should their rights be infringed.

Just this month, the High Court in Pretoria decided a case that provides a flicker of hope. In 2011, the Law Society of South Africa challenged South Africa’s former President Zuma’s role in the suspension of the SADC Tribunal, and on March 1, the court declared that the signing of the protocol that suspended the tribunal was unlawful, and therefore unconstitutional. The court further stated that if the intention was to withdraw from South Africa’s obligations under the SADC Treaty, the treaty in which the tribunal was created, the president should have obtained the consent of the South African Parliament. It is not clear whether the High Court decision will be taken on appeal.

The judgment has been applauded by civil society. According to the Southern African Litigation Centre, the judgment supports the notion that the executive ought not to have a blank check to take actions at the international level without due regard to constitutional values and existing rights. How strong is the will to resurrect the tribunal? South Africa remains the most active human rights defender in the region and the most progressive in using litigation as a tool to hold government accountable. One reason for this is the presence and work of South Africa’s very active civil society. Civil society in other parts of SADC has made statements on the death of the tribunal but still has to show the willingness to litigate. For example Zimbabwe’s legal watchdog, Veritas, expressed concern at the apparent death of the tribunal. Many human rights NGOs in the region have called for the revival of the tribunal. Examples include the League for Human Rights in Mozambique, Botswana’s Council for NGOs, and the Legal Assistance Centre in Namibia.

Importantly, the High Court decision opens the door to court challenges of a similar kind in other Southern African countries—though it is not highly likely that a similar suit will be brought soon. Under this momentum, though, it is possible that the new South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa, could get sufficient diplomatic support from neighboring countries to call for a summit of SADC heads of state, which could then decide on the re-opening of the tribunal. In particular, it will be interesting to see whether the new Zimbabwean president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, takes a friendlier and more open position on the SADC Tribunal than his repressive predecessor Robert Mugabe. Since Ramaphosa is already making friendly overtures toward Zimbabwe, it is likely that he could get support, should he consider this a priority. Indeed, these events may create the climate for supporting the re-opening of the tribunal. It is hoped that this will become a priority to governments in the region.

For the doors of the tribunal to re-open would be as welcome as soft rain in the desert.

[1] Economic Community of West African States

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A house of justice for Africa: Resurrecting the SADC Tribunal

April 2, 2018