On January 24, South Africa’s Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan presented South Africa’s 2016 budget. Creating and announcing the budget of the second-largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa is normally not an easy one, but it is especially difficult as the country is facing a number of well-known challenges. Gordhan has chosen a middle course when it comes to fiscal consolidation and has avoided an austerity budget. This is the right choice given the fragile economic conditions; however, Gordhan’s choice leaves structural measures as the main lever to reignite growth. The problem is that the budget appears to also have chosen a middle course on structural reform. Such a pace may not be fast enough for structural reforms to reignite growth. South Africa is still hanging by a thread, and markets are still going to demand more urgency.

What is the background for the 2016 budget?

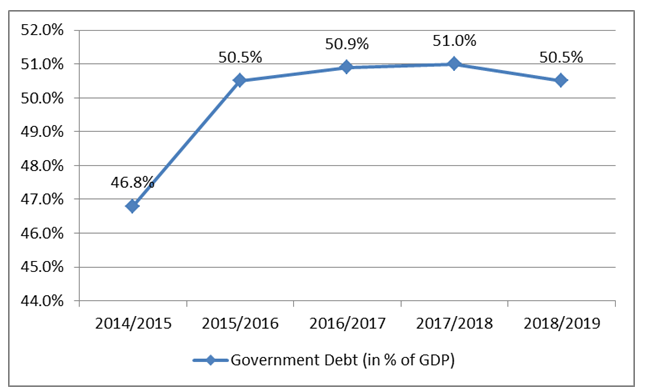

In South Africa, economic growth has been weak since 2010, and unemployment and inequality remain stubbornly high. Business confidence is weak, and the country is facing a drought, which could increase food prices in some areas. High energy costs and difficult labor relations have constrained growth. South Africa also faces current account and fiscal deficits, and debt has almost doubled in the past seven years. Debt is close to 50 percent of GDP and has contributed to sovereign credit rating agencies downgrading the country’s debt to the lowest investment grade level.

The external environment is also not supportive for South Africa as commodity prices have plunged, damaging the country’s important mining sector. In addition, from October 2014 to 2015, only five Sub-Saharan countries performed worse than the South African rand (R) when measured against the U.S. dollar.

How does the 2016 budget plan to address South Africa’s challenges?

To address the country’s economic challenges, the 2016 budget targets two levers: fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. This approach is not surprising, as there is a consensus that both fiscal consolidation and structural reforms are needed. First, fiscal consolidation is necessary for putting the country’s debt on a more sustainable path. As Gordhan stated on Wednesday, “We cannot spend money we do not have. We cannot borrow beyond our ability to repay. Until we can ignite growth and generate more revenue, we have to be tough on ourselves.” Second, structural reforms are needed to reignite growth because current constraints have led to declining productivity growth and to lower potential growth. The International Monetary Fund estimates that potential growth has fallen to 2-2.5 percent implying a negative output gap of 0.5-1.4 percent in 2014.

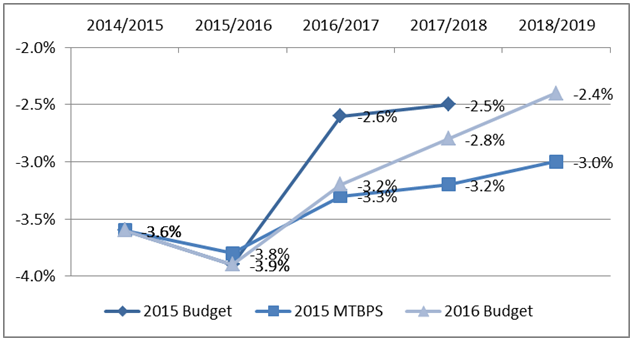

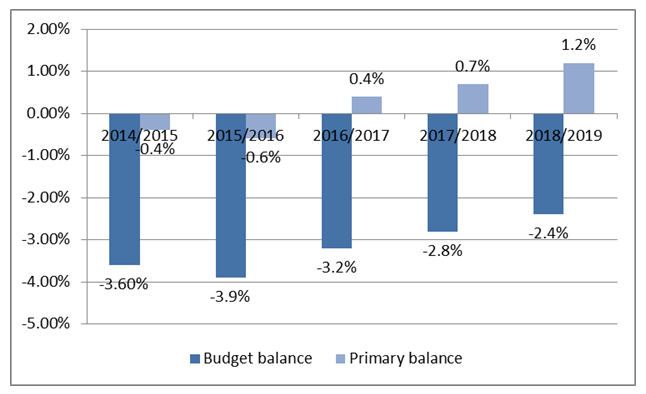

Let’s turn to fiscal consolidation first or, more importantly, to the pace of fiscal consolidation. South Africa’s 2016 budget accelerates the pace of fiscal consolidation compared to the October 2015 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) when the growth forecast was better and assumes that a primary surplus (the fiscal balance before debt service costs) will be achieved in the 2016/2017 fiscal year. The fiscal balance will be reduced to 2.4 percent by 2018/2019 from 3.9 percent in the current fiscal year.

Market participants have been disappointed by the pace of consolidation in the 2016 budget as they were expecting it to fall along the same line as the February 2015 budget (see Figures 1-3). The rand fell against major currencies, and the yield on the benchmark 10-year bond rose by about 21 basis points following Wednesday’s budget speech. However, markets rebounded the next day following a statement by Standard & Poor’s that the 2016 budget targets were consistent with the agency’s assumptions of planned fiscal consolidation and did not require an immediate credit-rating action.

Figure 1. South Africa: 2016 budget balance forecasts

Source: National Treasury

2015 budget refers to the February 2015 Budget.

2015 MTBPS refers to October 2015 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement

2016 budget refers to the February 2016 budget.

Figure 2. South Africa: 2016 budget balance and primary balance forecasts

Source: National Treasury

Figure 3. South Africa: 2016 budget government debt forecasts

Source: National Treasury

How will the consolidation path be achieved?

Finance Minister Gordhan has not chosen an austerity budget but has taken a middle of the road approach. This is understandable as austerity measures would have weakened a fragile economy and would have contradicted the government’s commitment to protect the vulnerable segments of the population. The 2016 budget intends to manage the size of the government workforce (a major source of expenditure), reduce the expenditure ceiling, and increase tax revenues. However, social spending will be maintained to protect the most vulnerable segments of the population.

On the expenditure side, the government intends to put restrictions on filling managerial and administrative vacancies and eliminate unnecessary positions; reduce transfers for the operating budgets of public entities; and renegotiate government leasing contracts. Technology will also be used to cut wasteful spending. The mandatory use of a new e-tender portal will increase procurement transparency and provide accessible reference prices. State-owned companies’ procurement plans and supply chain processes will be monitored by the chief procurement officer.

On the revenue side, the budget leaves the VAT rate unchanged probably because of its regressive nature and its possible negative impact on consumption, the economy’s engine of growth. Instead, the budget increases taxes on wealth, in particular on capital gains, on property sales above R10 million as well as on estate duty and donations. The 2016 budget plans to determinedly fight illicit financial flows and abusive practices by multinational companies and wealthy individuals. The South African authorities intend to act aggressively against practices such as transfer pricing abuses, misuse of tax treaties, and illegal money flows that encourage illicit financial flows. However, fighting illicit financial flows will take time to yield revenue results. The budget also considers a 30 cent per liter increase in the fuel levy. It will also hike so-called “sin taxes” on alcoholic beverages and tobacco products, and introduce a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. (South Africa has the highest obesity rate in sub-Saharan Africa.)

What’s the plan for structural reforms?

The 2016 budget is relying heavily on the National Development Plan (NDP) to guide its structural reforms so as to raise growth rates over the medium to long term. Public investment will target key areas of interventions, especially infrastructure. Electricity has been a key impediment to faster economic growth and the government plans to increase electricity supply and build infrastructure to encourage investment and create jobs. The national electricity company, Eskom will invest R157 billion to expand electricity generating capacity. In addition, over the next three years, the government has committed R796 million towards investment in housing, roads, public transport, water, and electricity.

Beyond infrastructure, the government is focusing on identifying and removing regulatory constraints in sectors that are less energy intensive and more labor intensive such as tourism, the ocean economy, agriculture, and agro-processing. Other areas of intervention include prioritizing spending on actions that have a direct impact on the economy, supporting small businesses—especially startups—and transforming cities through synergies between transport networks and jobs.

What are the risks to the fiscal outlook?

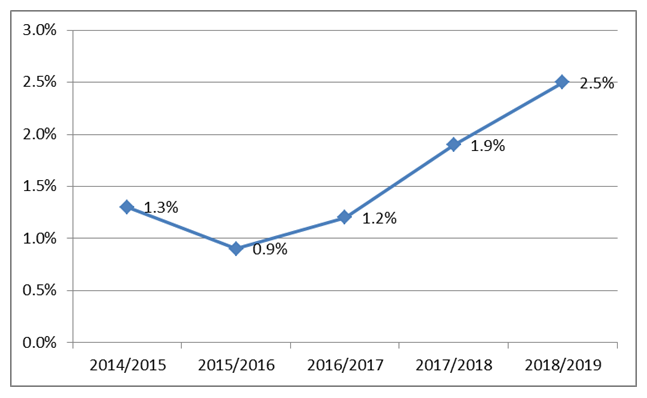

Gordhan faces a delicate balancing act. A more aggressive fiscal consolidation path could hurt the country’s fragile growth prospects. Growth is expected to reach a meager 0.9 percent in 2016/2017. Austerity would also have an impact on the hardest-hit segments of the population such as the low-skilled and the youth, which would go against the government’s objectives of inclusion and social cohesion. This may be a reason why the government decided not to increase the VAT rate.

The final decision seemed to complement the chosen fiscal consolidation path with structural reforms and increased public investment, especially in infrastructure, to revive growth. The budget expects growth to rebound quickly and reach 2.5 percent by 2018/2019 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. South Africa: 2016 budget real GDP growth forecasts

Source: National Treasury

I see a number of risks to the fiscal outlook including the difficulty of implementing structural reforms that will generate growth quickly. I am not also very clear on how the quasi-fiscal risk from state-owned entities (SOEs) will be managed.

The key question is whether South Africa will be able to quickly revive its growth as this budget assumes. As Gordhan put it, “if we do not get above 0.9 percent growth in the next year or two, we will have to do more of this balancing act, more of cutting expenditure, and more of raising revenue.” The need to achieve a 0.9 percent growth rate means that that the country has little room for error.

Interestingly, the same Standard and Poor’s report that calmed the markets also noted, “South Africa’s fiscal consolidation remains vulnerable to lower-than-expected GDP growth and shortfalls in revenues.” The rating agency also states that, “the fiscal trajectory continues to be exposed to contingent liabilities emanating from state-owned entities (SOEs) with weak balance sheets, which may require which may require more support than what the government has currently provided.”

The budget could have provided more details about how the government will limit the risks from SOEs and how they will help re-ignite growth. SOEs in South Africa have an asset base of over R1 trillion or about 27 percent of GDP and play a role in both fiscal consolidation and structural reforms because some of their debt is guaranteed by the government and because they cover a share of the planned investment in infrastructure. The budget acknowledges that there are issues to address in their governance, mandates, financing, and operations. It indicates that SOEs that are no longer necessary should be phased out and that for SOEs that have overlapping mandates, “rationalization options” will be pursued. Given the current level of government guarantees to SOEs that amount to R647 billion or 11.5 percent of GDP, the budget stresses that planned infrastructure financing will need to be done using co-funding partnerships with private sector investors. An appropriate framework for concession agreements and associated debt and equity instruments, as well as the appropriate regulation of the market structure, will be developed. These are all welcome policies but more details are needed to assess how they will impact the budget’s growth forecasts and the fiscal consolidation path compared to say, a privatization program.

The South African National Treasury does a good job of identifying two of the risks discussed above: “The main risks to the government’s fiscal consolidation plans are weaker-than-expected economic outcomes, inflation, and the financial position of several SOEs.”

The Treasury notes that a weaker-than-expected economic growth performance would reduce revenue growth and delay debt stabilization. Further increases in interest rates together with a weaker exchange rate and rising inflation would raise the cost of borrowing and increase the stock of debt. It also notes that food inflation has increased and that Eskom is seeking higher energy tariff, which would lead to higher inflation next year and, in turn, inflation-linked expenditures. The Treasury also recognizes that several SOEs are in financial distress and, in the event of default, the government will likely be called on to pay a portion of its guarantee to the SOEs.

The Treasury notes that if any of these risks were to materialize the government would need to consider contingency measures such reprioritizing spending, further reducing baseline allocations, or deferring new programs. It also notes that the government is working with SOEs to stabilize their balance sheets and implement realistic turnaround plans.

I agree that structural reforms are needed to re-ignite growth but the question is how soon can they be implemented and how quickly will they start to deliver? Market participants are looking for stronger measures than those in the budget. In the next months, implementation of the budget measures and their impact on growth will be critical for South Africa.

In sum, while the government is well aware of the challenges, the 2016 budget shows that it has chosen a gradual approach. In contrast, markets would have liked to see a shock therapy: a more accelerated fiscal consolidation path and privatizations. They may grudgingly accept the budget’s fiscal consolidation path as austerity measures would have weakened the fragile economy but they will be less forgiving on lack of progress on the structural front.

If the government’s gradual approach is to succeed, it will require more than just fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. It will require a third policy instrument, strong partnership including with the private sector and labor unions, which Gordhan’s speech often hinted at, insisting, in many instances, on the need for “partnerships amongst role players” in the South African economy.

To function, this tool requires elements that are not easy to quantify: of course policy certainty, but also trust, confidence, good governance. It is very telling that the Gordhan stressed that “in acting together we can address declining confidence and the retreat of capital, and we can combat emerging patterns of predatory behavior and corruption.” All South African stakeholders will need to work together if the budget’s projections are to be realized. There are really few options as the alternative would be to fall in a recession and risk a credit rating downgrade which would increase borrowing costs, weaken the rand, and discourage portfolio investments. That would be unfortunate for sub-Saharan Africa’s second-largest economy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

South Africa’s 2016 budget: Will Gordhan’s gradual approach deliver?

February 26, 2016