Like millions of frontline workers around the country, Lisa Harris, a cashier at a Kroger grocery store outside of Richmond, Va., will bring home a larger paycheck this holiday season. For the first time in her 14-year career at Kroger, Harris finally earns more than $15 per hour—about $1.50 more than she did before the COVID-19 pandemic began. But despite the pay bump, Harris doesn’t feel she is getting ahead.

“My money isn’t going as far,” Harris told us in November, reflecting on the impact of quickly rising prices like gas and food. “It isn’t sustaining my day-to-day life. But also, my job is harder. We are extremely understaffed. I am being asked to do more people’s jobs than I already was before…Morale is on the floor and people are threatening to quit.”

Media coverage about how American workers like Harris have weathered the pandemic offers mixed messages. Frontline essential workers have endured tremendous risks and made significant sacrifices to keep the country running during the pandemic, often for low pay. But in recent months, things have started to look up. Wages have risen, at least nominally, for many workers in supermarkets, warehouses, stores, and restaurants, and workers seem to be gaining leverage over employers. However, inflation—which is now the highest it’s been in nearly 40 years—is taking a large bite out of those raises and frontline employees are quitting their jobs at historic rates.

So, are frontline workers better off economically today than when the pandemic began? And if they are, is “better” even good enough for what they deserve?

To find out, we analyzed wages for U.S. hourly workers at 13 of the largest and most profitable retail, grocery, and fast food companies in America. (We conducted this analysis as part of a larger report on frontline workers in the pandemic economy, forthcoming in early 2022.) The 13 companies are all household names and among the most influential employers in their industries; together, they employ nearly 5 million U.S. workers. Using company-wide pay policies, we calculated the nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) change in average pay at each company between January 2020 and the end of October 2021. We confirmed the data through direct company communications.

Inflation has erased at least half of the average wage gains for frontline workers

We found that nominal pay (not factoring inflation) did increase, sometimes significantly, at all but two of the 13 companies. But inflation has erased most of the average gains. Since January 2020, inflation has risen over 7% through October 2021, and nearly 8% through November 2021. Over nearly two years as workers faced a global pandemic, the average wage increase, in real terms, at the average company we assessed was only 3% through October. (Assuming the 13 companies did not raise wages further in the last month, the average wage increase would have been just under 3% through November.) Without inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, the average pay increase would have been 10%.

…

In assessing the magnitude of raises, it is helpful to compare them to industry average gains for all workers: 5% in inflation-adjusted terms between January 2020 and October 2021 in leisure and hospitality and 2% in retail. At six of the companies, wage increases were substantial even after adjusting for inflation, ranging from 7% to 10%. But at the remaining seven companies, real wage gains were small or even negative. (Gap, Lowe’s, and Best Buy may have raised wages in some specific locations or for specific positions, but our methodology was not able to capture more localized gains.)

Table 1. Nominal versus real average wages

| Company | January 2020 average wage | October 2021 average wage | Nominal change | Real Change |

| Amazon | $15.75 | $18.50 | 17% | 10% |

| Walmart* | $14.00 | $16.40 | 17% | 9% |

| Starbucks | – | $14.00 | 15% | 9% |

| Macy’s | – | – | 15% | 8% |

| Chipotle | $13.00 | $15.00 | 15% | 8% |

| McDonalds | – | $13.00 | 10% | 7% |

| Target | $14.48 | $16.06 | 11% | 3% |

| CVS | $15.00 | $16.50 | 10% | 3% |

| Walgreens | $14.41 | $15.80 | 10% | 2% |

| Kroger | $15.00 | $16.25 | 8% | 1% |

| Best Buy* | – | $17.67 | 4% | -2% |

| Gap | – | – | 0% | -7% |

| Lowe’s* | – | – | 0% | -7% |

*When Walmart and Best Buy increased wages, they also eliminated performance bonuses for frontline workers. Therefore, these wage increases are overstated. For instance, Walmart raised its average hourly wage to $16.40 in September 2021, but simultaneously ended its quarterly bonuses, which averaged $1,400 in 2020. Accounting for the $1,400 in lost bonuses, the adjusted real pay increase for a full-time Walmart employee working 36 hours per week for 52 weeks a year would be just 2%, compared to 9% without adjusting for the lost bonuses. The wage increase at Lowe’s is likely understated in the chart as it does not account for the quarterly bonuses the company awarded during the pandemic.

Source: Brookings analysis of average hourly wage data via company reporting or direct communication. Wages adjusted using the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator through October 2021. Average wages are adjusted for Best Buy, Gap, Lowe’s, Macy’s, McDonald’s, and Starbucks from the month the wage increase went into effect.

Inflation has forced workers at many companies to count their real hourly wage increases in pennies

Another way to look at these wage increases is in hourly terms after adjusting for inflation:

…

Consider Kroger: The company raised its average hourly wage from $15 per hour in early 2020 to $16.25 per hour in October 2021, a difference of $1.25 per hour in nominal terms. However, due to inflation, a Kroger worker would need to earn $16.08 in October 2021 to have the same buying power as she did earning $15 per hour in January 2020. As a result, the real pay increase for Kroger workers is just 17 cents an hour through October.

Over the course of a month, this difference adds up. For a full-time Kroger employee working 36 hours per week, a $1.25 per hour nominal increase equates to a monthly increase of $180. Adjusted for inflation, the real monthly pay increase for this Kroger worker is less than $25.

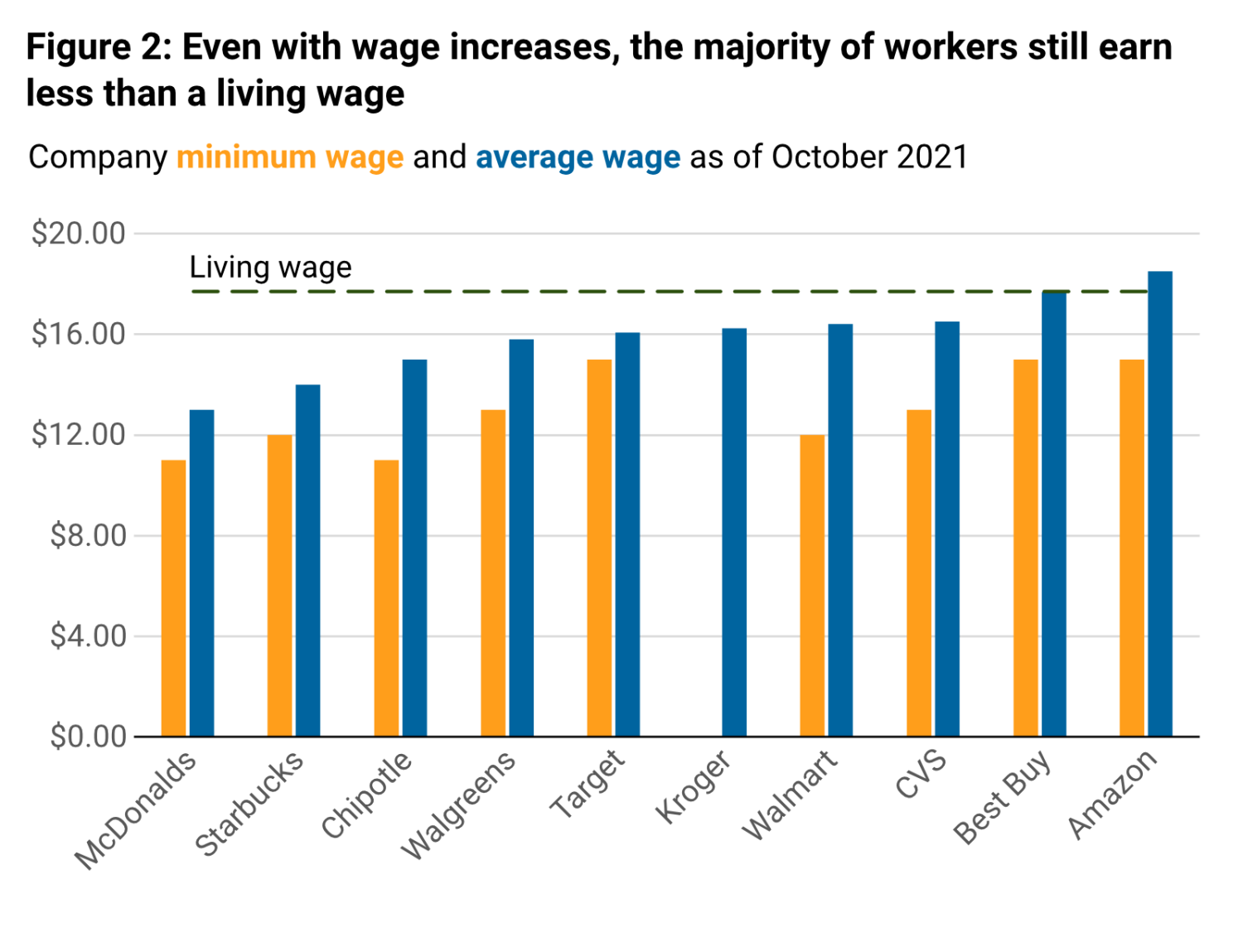

Most frontline workers are still not earning enough to get by

Headlines about rising wages for frontline workers—even rising real wages—often obscure the reality that wage levels are still low. In today’s inflationary environment, even as wages rise, so does the minimal threshold for an acceptable wage level. Inflation has increased the cost of day-to-day needs like food, rent, gas, and utilities. As of October 2021, the “living wage”—the wage that allows a full-time worker in a household with two working adults and two children to afford just the most basic necessities, with nothing left over for saving—was $17.70 per hour nationally, after adjusting MIT’s 2019 living wage for inflation through October 2021.

Of the 13 companies we analyzed, only Amazon pays an average wage that meets this subsistence standard. Not one of the companies pays a minimum wage that meets the living wage standard and ensures all employees can afford basic necessities.

And that is using the living wage for a full-time worker; a part-time worker would have to earn a lot more per hour to cover monthly expenses. The three fast food companies we looked at offer most of their workers only part-time hours; at the other companies, up to 40% of workers are part time. This means that the majority of employees at these companies have little chance of earning enough to support their families’ basic needs.

For instance, Chipotle has garnered positive media coverage for raising pay. The company’s real wage increase of 9% is the second-highest among the 13 companies we analyzed. But this increase was from a low base: Chipotle’s minimum rose from just $9 to $11, while its average hourly wage rose from $13 to $15. At the new $15 average hourly wage, a Chipotle employee working 25 hours per week—the hours worked by the median Chipotle employee in 2020—would take home less than $20,000 a year, which is only about half of the annual income required for basic survival. A Chipotle employee earning the company’s minimum of $11 per hour and working 25 hours per week would earn less than $15,000 a year—an income so low it would put a household of two under the federal poverty line.

We have a shortage of good jobs, not a shortage of workers

“COVID just underlined that we were underpaid and still are underpaid,” Lisa Harris, the Kroger cashier outside Richmond, told us. She described seeing colleagues pay for their own groceries with food stamps, despite the pay bumps. Harris said the low pay is the main reason her colleagues are thinking about quitting—and she understands why.

“I love seeing my customers and my coworkers,” she said. “I like serving my community. I want to be there when times are hard, which is why I am still there. But it is making it hard when you can’t provide for yourself. You feel like a failure when you can’t provide. It makes you question whether this is the right career for you even when you love what you do.”

After all the sacrifices, risks, and burdens that millions of frontline workers have endured over the past 20 months of the pandemic, many workers are earning more than they did at the start—but by much less of a margin than many of us assumed. Too few are earning enough money just to get by. Perhaps we should not be surprised, then, that workers are quitting their jobs at historic rates. Our analysis suggests that, at least at these 13 companies, the shortage is not in the availability of workers, but of good jobs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

With inflation surging, big companies’ wage upticks aren’t nearly enough

December 13, 2021