Wendy Edelberg, senior fellow and director of The Hamilton Project at Brookings, discusses the positive impact of immigration on the dynamism and fiscal sustainability of the U.S. economy. She also explains her research on the impact immigrants have on local, state, and federal finances. As a whole, immigrants are a net benefit to the U.S. economy, but based largely on immigrants’ education levels, the fiscal cost is disproportionately paid by certain state and local areas. Together with co-author Tara Watson, Edelberg proposes a way to redirect some of the federal gains to these communities, piggy-backing on existing programs.

- Listen to Dollar & Sense on Apple, Spotify, Google, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

TRANSCRIPT

[music]

DOLLAR: Hi, I’m David Dollar, host of the Brookings trade podcast Dollar and Sense. As we celebrate America’s birthday, an important topic for discussion is immigration. My guest today is Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow at Brookings and director of The Hamilton Project. As I see it, The Hamilton Project focuses on practical research on how to create a growing economy that benefits more Americans. Great name, by the way. I mean, Hamilton was one of our early immigrants to the United States. So, very appropriate. Welcome to the show.

EDELBERG: Thanks very much. And I very much like your description of what we do. So, it sounds right.

DOLLAR: So, immigration took a big hit during the COVID pandemic. Have we recovered now to pre-pandemic levels? Are we back to where we were? What’s the situation currently with immigration?

EDELBERG: So, frustratingly, the answer to that question is more complicated than you might think. So, first, stepping back, immigration has always been important in this country. So, historically, like on average between 1870 and 1910, approximately 15% of the population was foreign born. And that’s moved around decade by decade. But in 2021, for example, it was 13.6%. Just to give a sense of the numbers.

Okay, now, the cataclysm to immigration that was COVID. So, for example, in 2019, about 460,000 visas were issued over the course of the year. In some months in 2020, the number of offices that were issued was at times in the hundreds. That’s how much immigration just fell off a cliff in the early days of COVID.

Now it’s come back and visa issuance does look like it’s back. But what makes it complicated is first, immigration numbers come out with a huge lag, but also, census revised population statistics. And they give us updated numbers according to those revisions, but they don’t revise back. So, you can’t compare today’s estimates of the population with previous estimates of the population. So, you’ll see in the press some people have said immigration’s back, but that’s comparing apples and oranges because of this revision to the data that’s not reflected in the history.

So, my best guess, accounting for that complicated revision to history is that we’re still, insofar as immigration matters for the labor force, as much as 500,000 short of where you would have expected to be in the absence of the pandemic.

DOLLAR: Okay. So, we’re partly back?

EDELBERG: Partly back.

DOLLAR: Your assessment is we’re not all the way back?

EDELBERG: That’s right.

DOLLAR: And around that figure you mentioned around 14% of the population, that would be one in seven?

EDELBERG: Yeah, that sounds right.

DOLLAR: And I just want to be clear for our listeners, we’re talking about people who are born outside of the United States who’ve come here and are here during when census counts are made, and many of them are U.S. citizens now, and most of them are here legally. But we also, do have some undocumented workers and they would be part our best estimates of what the immigration population is in the U.S.

EDELBERG: That’s right. And I’ll go back and forth between using foreign born and immigrants to mean the same thing, which they essentially do. But someone who was born abroad but has been in this country for many decades would still be an immigrant.

DOLLAR: So, where immigrants fit into our labor market depends on their education level. So, can we characterize the average education of immigrants? I know this is a tough question because we really have an amazingly diverse group of immigrants coming from all over the world. But can we make some general points about the education level?

EDELBERG: So, immigrants are disproportionately both higher educated than the average population, but also, lower educated than the average population. It’s that they’re there’s fewer of them in the middle than would be true if they if they matched the population of what we call native born people.

So, foreign born people are most heavily represented in the population that does not have a high school diploma, for example. And consistent with that, a foreign-born workforce is disproportionately concentrated in occupations with lower average wages like the service sector. But, a third of adult immigrants in the U.S. have at least a bachelor’s degree. And in fact, the statistic is amazing, almost 20% of all of those in the U.S. with a graduate degree are foreign born. So, we have lots of people at both ends of the education spectrum.

DOLLAR: Right. So, that’s actually quite interesting. And if I could just editorialize and you can correct me, but it seems to me in some ways that might be less disruptive of our economy in a sense, the fact that we’re getting people at the low-skilled end and then we’re getting lots of people at the highly skilled end. If everybody were in the same skill class, you know, then it could have a pretty big effect on relative wages. Am I right about this or … ?

EDELBERG: Well, so, you’re right in that the system all works best for everybody when the skills of immigrants complement the skills of the native population, rather than act basically as substitutes for the skills of the native population.

So, we have a lot of evidence that when an immigrant comes in who has less education, we see the relative wages of those with more education actually go up because those are complementary sets of skills.

But conversely, when immigrants with lower education come into the United States, we see wages of similarly situated people in the U.S. who have less education, who, let’s say, only have a high school degree, we see their wages fall, or at least their relative wages fall because they they’re more substitutes.

And just drilling down one more one more point on this whole idea of substitutes. In fact, the people who see the biggest hit to their wages when immigration goes up are recent immigrants. So, when immigrants come in who have less education, the most downward pressure on wages that we see across the population are immigrants who’ve come in recently who also, have less education.

DOLLAR: That’s extremely interesting. I’m aware of some cases where you get immigrant populations in parts of the U.S. that are opposed to further immigration. It always seemed a little odd to me, but what you’re saying makes a lot of sense.

EDELBERG: This is the whole thing of pulling up the ladder, that’s the metaphor that people use. You get on board and then you pull up the ladder.

DOLLAR: Right. So, we’re not going to get into the politics of immigration.

EDELBERG: Yeah yeah yeah, but that is one of the impetuses.

DOLLAR: Yeah, but those comments you just made give us a lot of insight into why it’s controversial for certain populations and why it’s less controversial for others. Especially interesting that even if you’re highly educated and there are more highly educated people coming and you think that might create competition, I like your point that in many cases it’s complementary.

EDELBERG: The short answer is it depends. So, if you are part of a highly educated workforce that has a lot of competition from a highly educated immigrant workforce, just like we talked about for immigrants and native populations with less education, you may actually see downward wage pressure because you have immigrants coming in who are highly skilled, just like you’re highly skilled, and they are competing for jobs, the exact same jobs that you’d be competing for.

DOLLAR: Yeah, that makes sense. Now, most economists I know are enthusiastic about immigration and it’s an important part of globalization, that’s why it’s a great topic for us. And most economists are enthusiastic because it has positive effects on the growth and the dynamism of the economy. So, can you walk us through what are some of the channels through which immigration affects the macroeconomic performance—growth, fiscal sustainability, these kinds of issues?

EDELBERG: Yeah, absolutely. So, we just talked about a bunch of the distributional effects, and I’ll come back to those in a second. But now the way I’m going to take your question is that it’s really about how immigration affects the aggregate economy. So, the economy on average.

So, the first most obvious place to start is population growth and labor force growth. So, foreign born people accounted for half of the growth in the U.S. labor force between 2010 and 2018. Half. That’s a big number. And over the next decade, projections which look utterly reasonable to me by the Congressional Budget Office show that immigration will account for about three-quarters of the overall increase in the size of the population. So, over the next decade, immigration accounts for three quarters of the overall increase in the population. So, the other quarter, just to be clear, is because there are more births and deaths, but three-quarters is because of immigration.

That will get that fraction is actually going to get larger and larger over time until what is widely expected is that fertility gets low enough that, in fact, aside from immigration, we actually have net shrinking of the population. And so, immigration, more than accounts for all of the population growth within the next couple of decades. So, population growth critically important for its effect on the aggregate economy.

And generally speaking, immigrants are far more likely to work than people who are born in the U.S. They have higher labor force participation rates. So, everything I just said is even more important when it comes to the labor force. All right. So, that’s just people.

Now, let’s talk about productivity growth. And here we know we have a ton of evidence that immigration spurs productivity growth. We know that, for example, immigrants receive patents at twice the rate of the native-born population. We know that immigrants, broadly speaking, have a complementary skillset. So, they come in with different skills than the native population has. And the combination of those skills leads us all to be more productive. So, we know we have tons of evidence that that’s what happens in the aggregate. I am acutely aware that there are distributional effects and we need to be aware of that and make sure that—I’m just going to use an incredibly tired phrase—but that the winners compensate the losers, because if all we’re worried about is what happens to people’s wages, some people will feel negative effects of this, but let’s not lose sight of what happens to the aggregate economy.

DOLLAR: Wendy, I do a lot of work on the Chinese economy and certain amount on the Japanese economy as well. These are the second and third largest economies in the world after the United States, and they’re facing really serious labor force decline. Tt’s already started in Japan. Actually, the working age population has peaked in China and it’s going to start to decline. And it’s very hard to reverse that. And these are not immigration-friendly societies. They’re densely populated. So, even though the labor force is starting to decline, they have a lot of old people, they have a lot of people. And you just do not see a lot of immigration into a place like China or Japan. And so, that really affects their economic prospects. And what you were just describing about the U.S., I sometimes suspect immigration is our superpower, basically.

EDELBERG: And where do some of the best and brightest from China and India want to go? They want to come here. I mean, this is why I started with the statistics that I started with. We are a country of immigrants. And absolutely, this is one of our superpowers.

DOLLAR: But you’ve emphasized they’re also costs associated with immigration. We’ve talked a little bit about the distributional consequences, but there’s also fiscal costs. And this is the point of some of your recent research. So, can you talk us through a little bit on these fiscal costs? And as I understand your argument, a lot of these are local and, in fact, a lot of the benefits end up increasing federal tax collection. So, if you’re going to have, as you said, which is classic economists speak, you don’t have the winners compensate the losers. Probably some kind of fiscal redistribution is going to be necessary. So, tell us a little bit more about that.

EDELBERG: Yeah, I should probably apologize for that again. But. All right. So, I wrote a policy proposal with a colleague here at Brookings, Tara Watson, and what we relied on for the statistics that I’m about to describe is from a National Academy of Sciences report. And they looked very carefully at what the fiscal effects are from adding one additional immigrant into the United States. And here’s what they found. And a lot of people have looked closely at these numbers, so, they’re trustworthy.

So, at the federal level, an immigrant is said to contribute on average a little over $1,000 more in revenues than they receive in federal benefits. So, in other words, bring in an additional immigrant and the federal balance sheet looks healthier as a result of expanded immigration. Now, this is partly because immigrants pay a whole lot in taxes, and this is partly because recent immigrants actually aren’t eligible for a whole slew of federal benefits. So, immigrants are good for the federal balance sheet. Okay.

But that same report also, looked at what immigration does to state and local finances. And it found that an additional immigrant actually costs state and local governments about $2,000 more in spending that they incur at the state and local government level relative to the taxes that they receive. And this is just the story that we told for the federal government but in reverse. They get less in taxes because income taxes and sales taxes are just lower at the state level. But at the same time, most of the benefits that you get at the state and local level immigrants are eligible for. And even more importantly, their children are eligible for, because the biggest costs here are to provide education to the children of immigrants.

Now, there are lots of different ways of looking at these numbers. We can also, look at them over a 75-year like essentially life span, because when the immigrants come in, they’re typically not at their peak earnings so their peak earning years are still well ahead of them. And their children typically earn more than they do. And so, they have earnings and so, they’re going to pay tax revenues over the course of their lives. And so, you can look at what the fiscal effects are of an immigrant, not just in one particular year of snapshot, but over the 75-year period.

And there what we see is that the net fiscal benefit to the federal government is between $100,000 and $300,000. So, there’s a huge range because you have to make a whole lot of assumptions if you’re going to talk about what the net present value is over a 75-year period, but it’s clearly positive and pretty significantly large for the federal government.

At the state and local level what we find is that there’s just a small net fiscal benefit. So, it’s a couple thousand dollars. It’s trivially small, but it is positive, which is to say that despite all the expenses, particularly on education, that state and local governments have to do for immigrants and more importantly, their children, they make enough back in taxes to essentially over a lifetime pay for those expenses. But because of the timing, it takes a long time for them to earn back that money in a fiscal sense.

So, the effects on state and local governments, though, differ by the education of the immigrant. So, we can look at those same 75-year calculations and look at how they differ for state and local finances for an immigrant who comes in without a high school degree versus an immigrant who comes in with a bachelor’s degree. So, for an immigrant who comes in without a high school degree, all of the costs, all of the increases in spending that the state and local governments are going to incur for that immigrant and that immigrant’s children are going to outweigh the taxes that the state and local government can expect to get over the 75-year period. It’s going to outweigh by between $80,000 and $90,000. Which is to say, if an immigrant comes in to some area, the state and local government—the area that they’ve moved into—is going to incur a fiscal burden for an immigrant without a high school degree of between $80,000 and $90,000.

However, if the immigrant has a bachelor’s degree, it’s completely flipped. And in fact, the state and local government will is estimated to get more in taxes relative to all of the spending obligations that they incur to the tune of between $120,000 and $130,000. So, immigrant with less than high school degree net fiscal burden on state and local governments over an entire life span of between $80,000 and $90,000. Immigrant with a bachelor’s degree or more is a net fiscal benefit to state and local governments over a 75-year period between $120,000, $130,000.

So, one reason to go through all of the pain and suffering of going through these numbers is to give you a sense of why different communities may have a completely different understanding of immigration. So, communities that have disproportionately welcomed immigrants that have bachelor’s degrees may say there is nothing but fiscal upside. What the heck? Why are we having this conversation about the burden of immigration? Immigration is not a burden at all.

And that just that picture may just be completely unrecognizable to a community that is disproportionately welcoming immigrants without high school degrees, for example. And they’re experiencing pretty significant fiscal burdens at the state and local government level. And this is all regardless of what’s happening to the federal government, because the federal government’s doing great, basically, no matter what level of education the immigrants have.

DOLLAR: Right, so, what I take away from that is all of the all of the immigrants essentially have a net positive effect on our fiscal situation think thinking of a consolidated local central government together, local-federal government together. But then when you break it down by skill group and between the central and the local basically the unskilled immigrants create a fiscal burden for local government, even though if you factor in what’s happening at the federal level, it’s a net benefit for the economy.

EDELBERG: You said very nicely and this is largely because the federal government can pretty easily pick and choose what benefits it wants to allow immigrants to be eligible for.

DOLLAR: I actually love this about America, that if there’s a school kid in the school district, they’re entitled to go to public school. Doesn’t matter if they’re immigrant, doesn’t matter even if they’re in the country legally, they’re entitled to go to school. I think it’s a great thing about our system. But I can see how that could create a strain for certain local governments.

EDELBERG: Absolutely.

DOLLAR: And what that brings us to next is you have a really nice interactive tool on your website. I’m going to let you explain it. It’s basically as I look at it, it’s trying to show us where some of this local fiscal burden is particularly acute.

EDELBERG: So, what Tara and I started with was this this understanding and deep appreciation for the fact that immigration is, as we said at the beginning, one of our superpowers. It is absolutely essential for robust economic growth. It is a central aspect of the U.S. economy. And we just need to do it better. And we need to recognize that not everyone in the United States is experiencing all of the costs and enormous benefits of immigration equally.

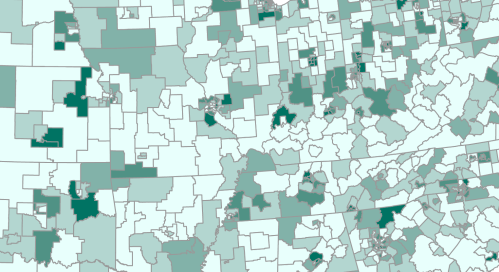

So, we zeroed in on this population that the literature tells us creates a disproportionately large fiscal burden on state and local governments. And so, using census data, we estimated something that we call an immigration impact index, which is the share of the non-institutionalized adults in a local area that have arrived in the past five years and do not have a college degree.

And so, we did the past five years because we know that, you know, I threw in at one point that when immigrants initially come to this country, we have a lot of evidence that they are not yet at their peak earnings. They’re going to earn more over time. And so, recent immigrants are going to require more and benefits and probably pay less in taxes than immigrants who have been here for a while. And we wanted to focus on those without a college degree for all of the numbers that I went into in enormous detail.

And so, if we look at this population, we can see that nationwide the number of what we’re calling impact index immigrants is a bit less than 1% of the adult population or somewhere between two and a quarter, two and a half million people. And so, at the state level, as maybe won’t surprise you too much, the places where we see the highest proportion of these index immigrants is in Florida, Texas, California, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, like states that probably don’t surprise you.

But in some communities, like for example, in Florida, New Jersey, New York, Texas, in parts of those states, they represent 6% or more of the local adult population. So, there are some areas that where this population of recent immigrants without a college degree is like a recognizably large percentage of this population, and that local government is going to be experiencing a pretty notable fiscal burden.

But then what our tool allows you to see is how incredibly varied the preponderance of these immigrants are actually across the entire United States. So, like at the local area, there are areas near Wichita and Topeka in Kansas—

DOLLAR: —I noticed that there were a lot of communities along the Mississippi River—

EDELBERG: —Yeah, where it’s more than 2% of the population. There are counties in central Oklahoma where it’s more than 2% of the population. And there there’s like a mountain region in northern Georgia where they’re 2% of the population. So, one of the things was just to just to show readers and users of this interactive that, in fact, this is not this is not an issue that is only about California. This is not an issue that is only about New Jersey or Florida. There are counties all over the country who are welcoming these immigrants and are disproportionately bearing the fiscal burden of taking them into their communities.

DOLLAR: So, our Dollar and Sense web page, which has this interview, will connect or link to your interactive tool. So, I encourage people to look at it because I thought it was really interesting. I love that kind of thing. Last question for you, Wendy, is is there a simple, administratively easy way we could deal with this?

EDELBERG: There is a very simple and straightforward way to do this. It, of course, will cost money. But what it really means is a redistribution of the fiscal benefits of immigration from the federal government to the state and local governments. So, we size that the fiscal benefit that really should be transferred from the federal government to state and local governments should be about $2,500 per what we’ve called index immigrants, impact index immigrants. So, those who have recently arrived without a college degree. And that’s partly based on the National Academy of Sciences report, it’s partly based on looking at some other things about what we’re looking about with recent immigrants, what we’re looking at with education, knowing that we’re not incorporating the overall productivity gains of immigration.

But in any case, $2,500 we think will basically cover the fiscal burden to these state and local governments. And we want to put the majority of that through the education system. And we want to put about a third of that through the health care system. And you might say, yeah, but don’t we already give like local school districts extra money if they have to teach students English as a second language? And listeners might be shocked and horrified to know that the additional resources that a school system gets to teach English as a second language is $150 per student.

Not only is that not enough to just do the additional teaching, but we also, wanted to think about getting additional resources to the education district for all the costs that come with welcoming immigrants with less than a college degree into your community: the community resources you need to give them, the after school resources you need to give them, the ways that they’re that that these students that the students of immigrants might need additional resources from teachers to get them caught up.

There are many and varied ways that recent immigrants with less than a college degree will need more resources in an education district. And so, not only did we want to give a lot more, And so, we size at about 1,700 dollars per impact index immigrant, but we also, wanted it to be not tied to any particular type of type of cost. There are no particular requirements. It goes into the education system.

But then that district is free to spend the money as they see fit. Maybe they’re doing a spectacular job spending on these children of immigrants. But maybe then what they’re doing is they don’t have the resources left over to spend on native children. And so, we didn’t want to say, here’s money and you have to spend it in this way on this population. What we wanted to say is we recognize that there is a fiscal burden to your educational district and here is money from the federal government to redistribute some of the fiscal benefit that the federal government gets to you, education district, who is experiencing acutely the fiscal burden.

And we have a somewhat similar way of thinking about getting more resources into the health care system to provide health care benefits to these communities that are welcoming immigrants without college degrees.

DOLLAR: So, I love the administrative simplicity. Sometimes we try to do good, but it’s complicated. There’s a lot of reporting requirements, and if you can do it administratively simply, then that’s really the way to go.

EDELBERG: What’s amazing is that we actually do this for school districts in a completely different context without batting an eye. And it’s called Impact Aid. So, school districts can say we need money from the federal government because the federal government has basically created an area in our school district that has essentially reduced our tax base but added fiscal burdens to us.

So, a completely obvious example here is a military base. So, if the federal government comes along and plops a military base down in the middle of a community, that military base isn’t paying state and local taxes. But it is saying you have to educate these children who live on this military base. School districts are allowed to apply for what is called Impact Aid and say, because of federal policy you have actually imposed a fiscal burden on us without giving us the resources to be able to pay for it, so you need to give us money. We don’t bat an eye. We say that is fine because of a federal policy decision. We have created a fiscal burden on these state and local governments. We are going to transfer money to you.

So, in fact, what we say is let’s basically use that exact same system and say immigration policy has basically created a fiscal burden on state and local governments.

DOLLAR: I’m David Dollar, and I’ve been talking to my colleague Wendy Edelberg about immigration, which is we decided is America’s superpower. It’s good for the economy. It’s good for the consolidated fiscal situation of the United States. But Wendy’s research, together with colleagues, points out that a lot of the costs are borne at the local level, particularly for education and health. And she’s got a nice, simple proposal for a transfer mechanism so that we essentially redistribute some of the benefits of immigration to make sure that the costs are covered at the local level. So, thank you very much, Wendy.

EDELBERG: Thank you. It was fun talking.

DOLLAR: Thank you all for listening. We release new episodes of Dollar and Sense every other week. So, if you haven’t already, follow us wherever you get podcasts and stay tuned.

[music]

It’s made possible by support from supervising producer Kuwilileni Hauwanga; producer Fred Dews; audio engineer Gastón Reboredo; and other Brookings colleagues. Show art is by Katie Merris.

If you have questions about the show or episode suggestions, you can email us at Podcasts at Brookings dot edu. Dollar and Sense is part of the Brookings Podcast Network. Find more podcasts on our website, Brookings dot edu slash Podcasts.

Until next time, I’m David Dollar and this has been Dollar and Sense.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastWhy immigrants are America’s superpower

July 3, 2023

Listen on

Dollar and Sense Podcast