Housing affordability is one of the most salient economic and political issues facing U.S. households and policymakers. And local governments play an essential role in regulating housing production, with zoning laws determining how much land is allocated for housing versus other uses, what types of homes can be constructed where, and the process for building new homes.

Over the past several years, cities and counties across the U.S. have been experimenting with new strategies to increase the supply of housing, such as zoning reforms that make it easier to build “missing middle” housing or convert vacant offices into apartments. In particular, cities and inner-ring suburbs with little undeveloped land need to think creatively about how to develop—or redevelop—more homes on small amounts of land.

Our recent paper illustrates one possible approach to expanding housing supply, based on the experience of Washington, D.C., which adopted a new zoning code in 2016 that reallocated land in some non-residential areas for high-density housing, but largely preserved zones that only allow single-family homes. We look at spatial patterns of housing growth from 2000 to 2020, and compare that with changes in zoning during the same period. We find that a very large share of housing growth over this period occurred in a handful of neighborhoods, some of which had been rezoned from non-residential purposes—a strategy with both strengths and limitations.

Housing growth in Washington, DC was highly concentrated in a few centrally located neighborhoods

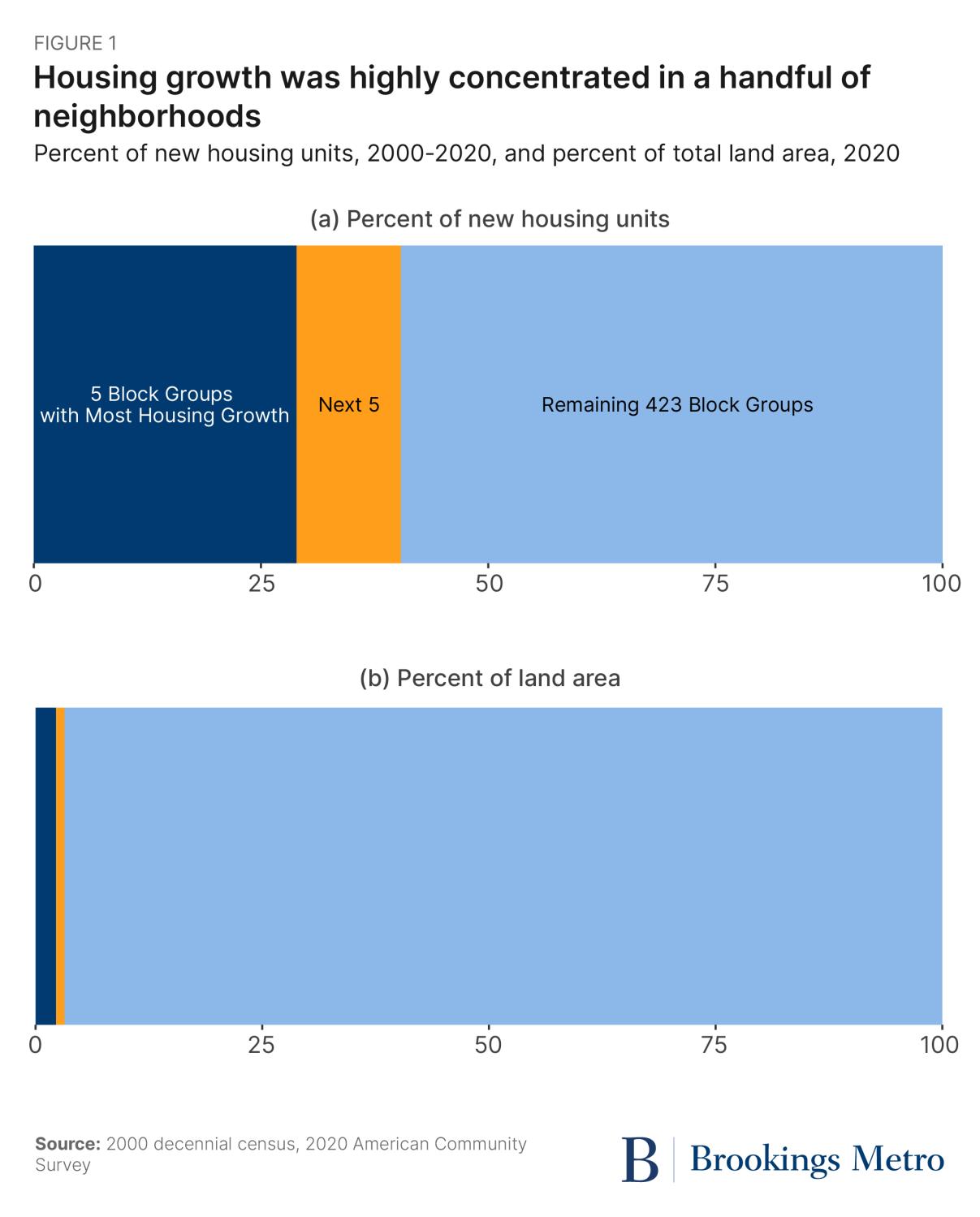

Like many other large, coastal cities, Washington, D.C. experienced strong housing market fundamentals for most of the study period (with a notable dip during the 2007-09 Great Recession). From 2000 to 2020, the District’s population grew by around 130,000 people, a roughly 20% increase. However, population and housing growth were not spread evenly across the city. The five highest-growth neighborhoods accounted for nearly 30% of the increased housing built in the District from 2000 to 2020, and the next five highest-growth neighborhoods produced 10% of new housing—even though these 10 neighborhoods collectively occupy about 5% of the District’s land area (Figure 1).

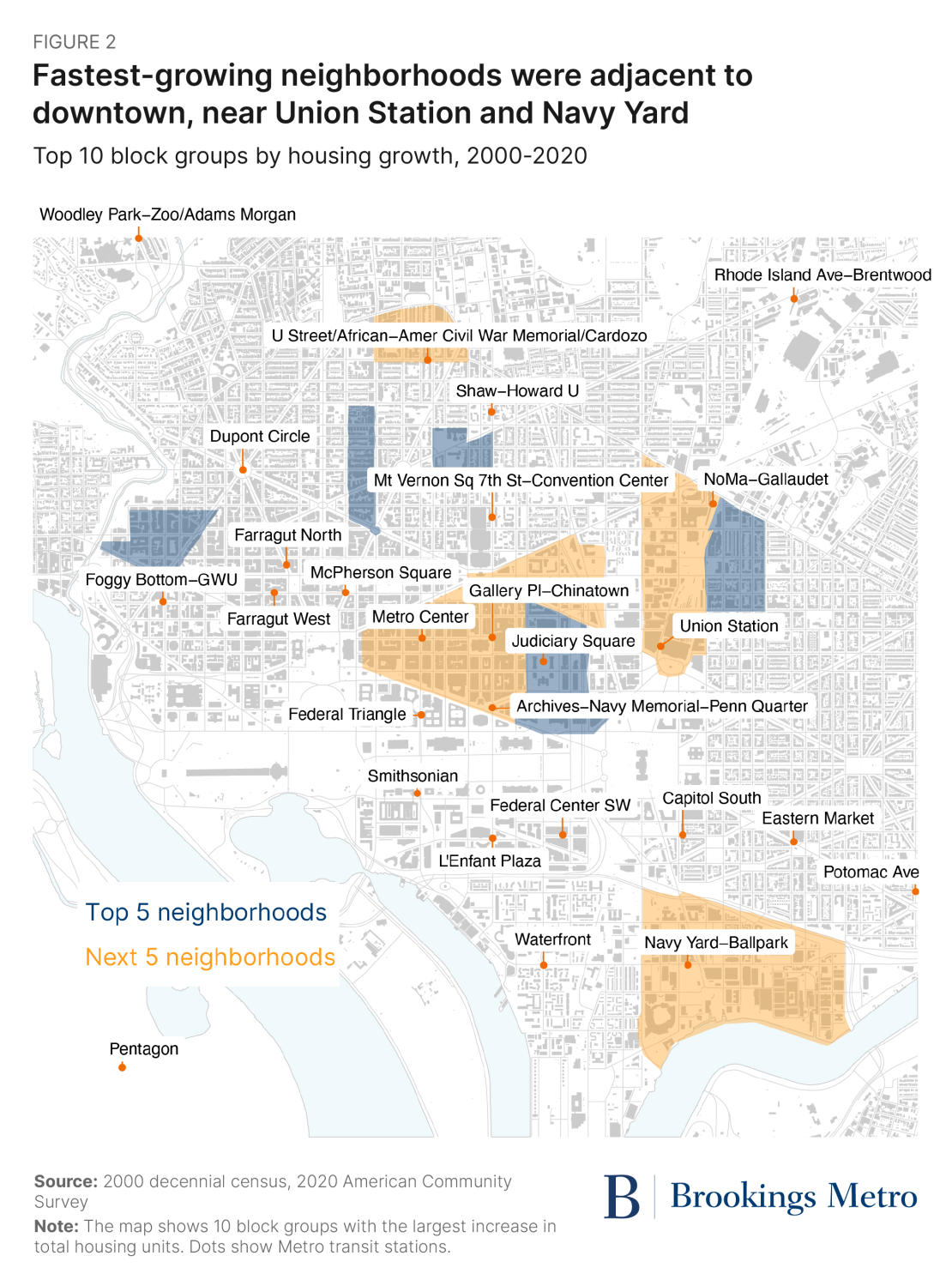

Most of these 10 high-growth neighborhoods are located in the central core of the District, which contains a large share of the region’s employment (Figure 2). Several high-growth areas are clustered adjacent to downtown and around the Union Station/NoMa neighborhood. Nine of the 10 areas are north of the National Mall, with the lone exception of Navy Yard, home to the Nationals baseball stadium.

The District’s zoning reform added housing capacity in non-residential areas, but did not up-zone single-family-only neighborhoods

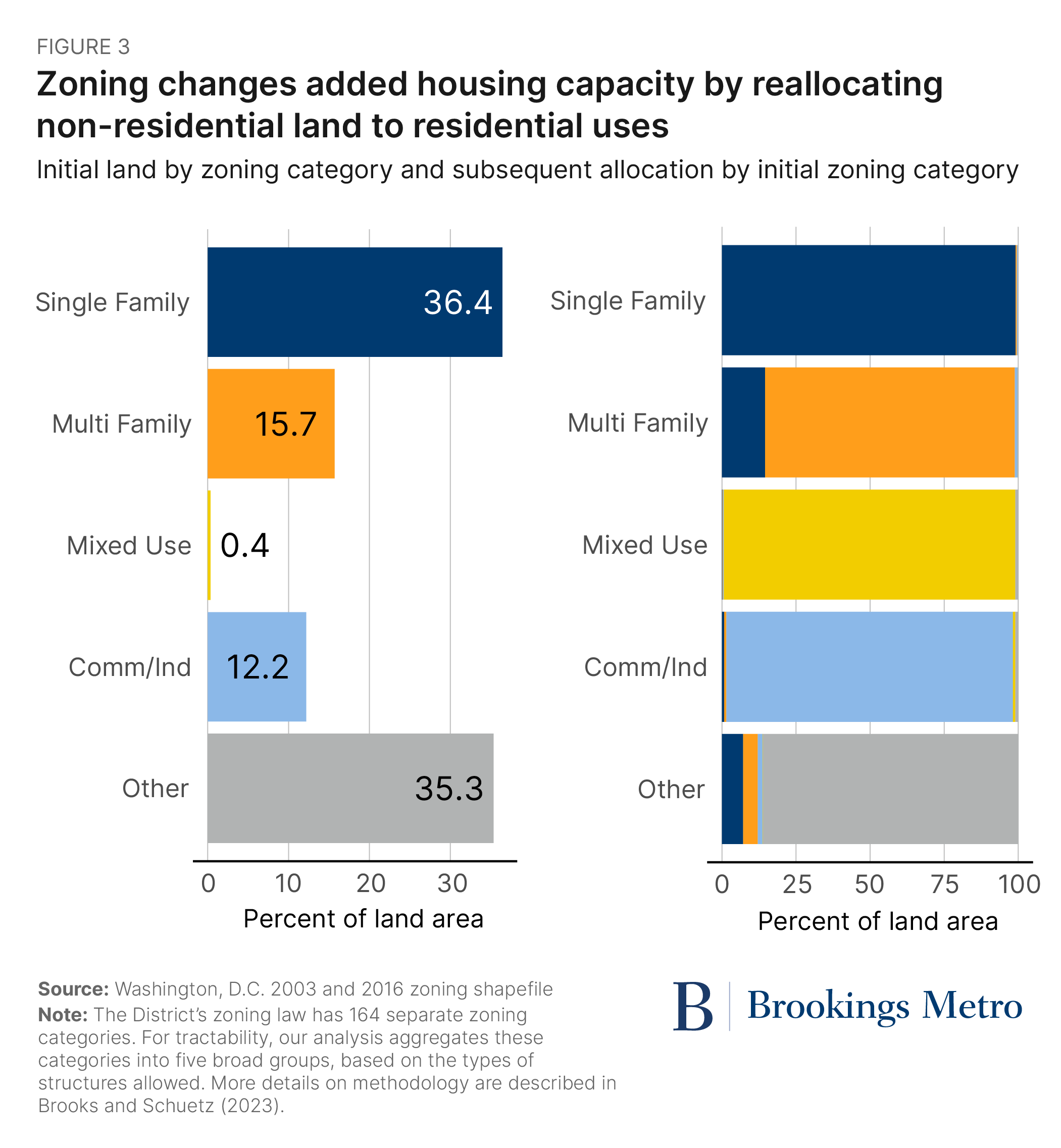

In 2016, a new citywide zoning law went into effect in Washington, D.C., codifying many years of small-scale, primarily technical revisions. Most neighborhoods saw relatively little change in the share of land allocated to different types of uses and structure types. Rezoning can be used to increase housing capacity through two different channels: legalizing housing on land previously zoned for non-residential uses (e.g., changing the designation from “Industrial” to “Residential”) or increasing the density of housing that is allowed in residential areas (e.g., legalizing apartments in zones that only allow single-family homes).

Our analysis finds that the District primarily added capacity for housing through the first channel: rezoning a small amount of previously non-residential land to allow housing, as shown in Figure 3. Specifically, portions of land in the “Other” category as of 2003 were rezoned as single-family, multifamily, or Commercial/Industrial. This category makes up a large share of the District’s land, so in theory could continue to be repurposed to allow more housing. In practice, much of the “Other” land is occupied by government facilities, including parks owned by the National Park Service, which are unlikely ever to be converted.

Notably, nearly all the land zoned exclusively for single-family homes in 2003 retained that classification. About 15% of the multifamily-zoned land in 2003 was down-zoned, or reclassified to allow only single-family homes. The down-zoned neighborhoods are predominately located in Wards 7 and 8, east of the Anacostia River—a pattern that invites future research.

Single-family-only neighborhoods were largely protected from zoning changes—and added very little housing

Many of the zoning reform efforts underway across U.S. cities are aimed at increasing housing capacity in low-density, amenity-rich residential neighborhoods. To date, Washington, D.C. has not adopted—or seriously considered—citywide up-zoning. Most single-family-only neighborhoods in the District, including transit-rich areas such as Cleveland Park and Kalorama, have little zoned capacity to add more housing; parcels are occupied with existing homes, and the only feasible changes are replacing small, older single-family structures with larger, generally more expensive single-family structures.

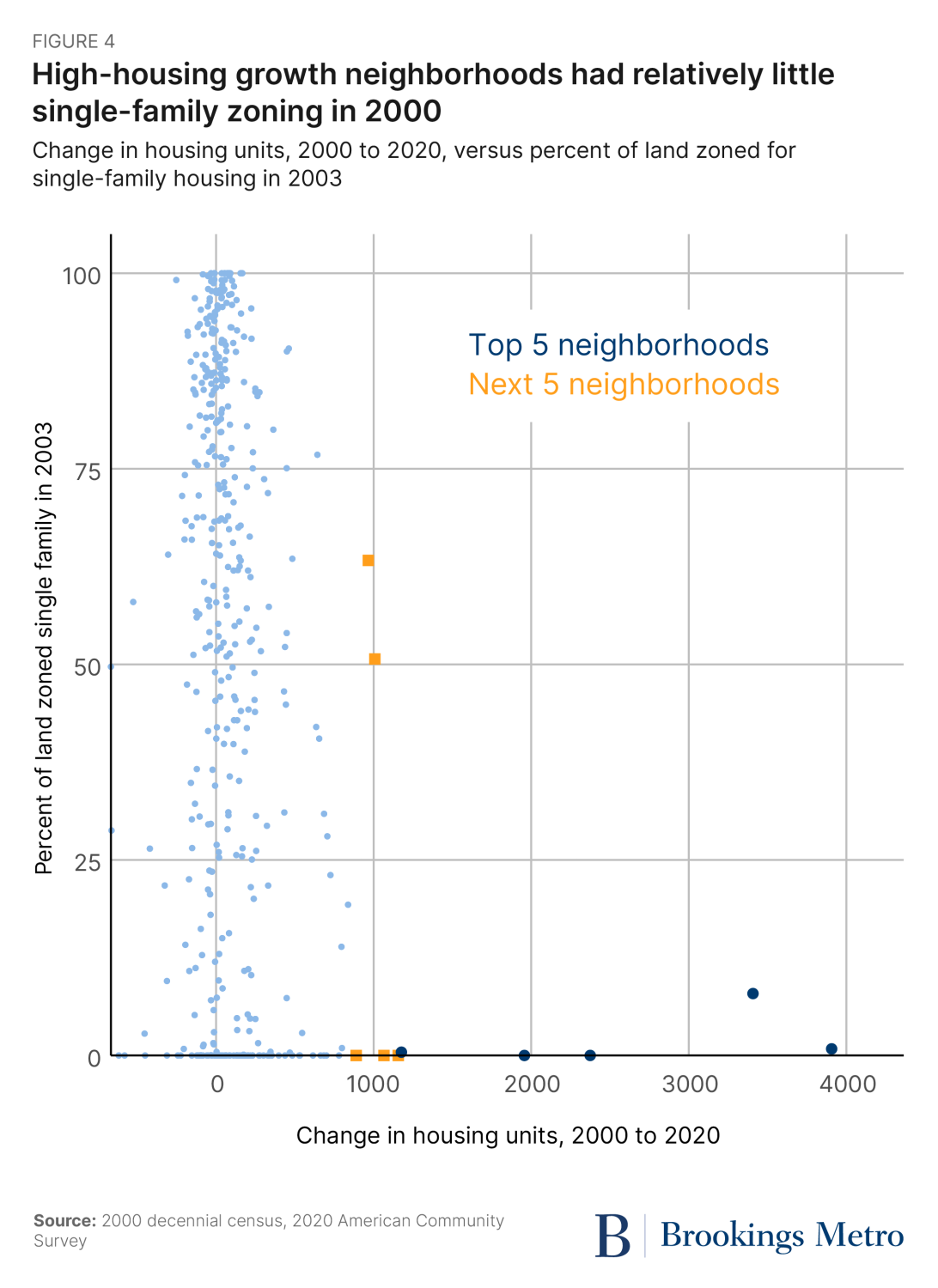

One notable feature of the District’s high-growth neighborhoods is that they had only a small fraction of land zoned exclusively for single-family homes as of 2003 (Figure 4). While the median Washington, D.C. neighborhood had about 60% of land zoned exclusively for single-family homes in 2003, the five neighborhoods with the most development had less than 8% of land zoned exclusively for single-family homes, and two had no single-family-only land.

The pros and cons of concentrating housing growth

The District’s strategy of reallocating underused non-residential land to housing has been successful at creating substantial amounts of housing over the past 20 years. Yet concentrating development in a handful of neighborhoods has both strengths and limitations.

High-density development in infill locations creates economies of scale for developers. Soft costs of development (e.g., financing, design and engineering, legal approvals) are lower per unit of housing for large-scale projects, while vertical development is more profitable in places where land is expensive. Concentrating housing in areas well served by public transit benefits the city—and the environment—by allowing more people to live car-light lifestyles. Neighborhoods such as NoMa and Navy Yard support substantial amounts of new retail, restaurants, and entertainment, which creates additional tax revenues. And politically, it was easier for the city to permit large-scale development in areas with fewer pre-existing neighbors to complain.

But there are also limitations. Not all non-residential land can be easily converted to housing—much of the land in the “Other” zoned category consists of protected open space such as parks and federally owned land that the District does not control. While the federal government’s real estate footprint is unique to the District, other large cities face similar situations with institutions such as churches and universities. At what point will the supply of potentially convertible land be used up? How will the strategy change going forward? And to what extent do newly empty office towers present a similar opportunity for residential growth?

While there is clear political appeal to keeping low-density residential neighborhoods largely unchanged, this strategy also raises serious equity concerns. Politically, concentrating development fends off the anticipated wrath of highly engaged “homevoters.” In addition, replacing decayed industrial infrastructure with high-value residences yields more municipal tax revenue, potentially benefitting all residents.

That said, insulating the District’s affluent, mostly white neighborhoods from new development means continuing to limit access to the economic and social resources in those areas, such as high-performing public schools, public transit, and healthier environmental quality. Avoiding short-term conflicts over zoning changes may delay addressing long-term economic and racial disparities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).